Warning the World of a Ticking Time Bomb

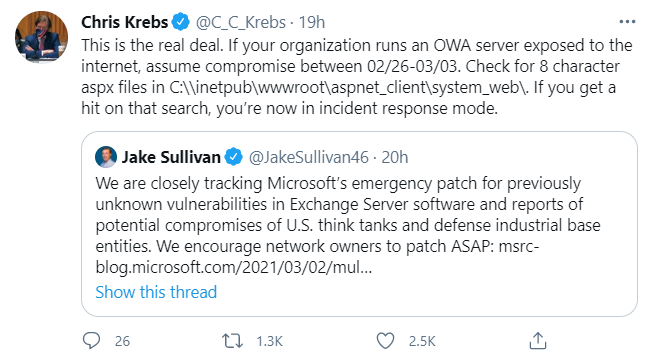

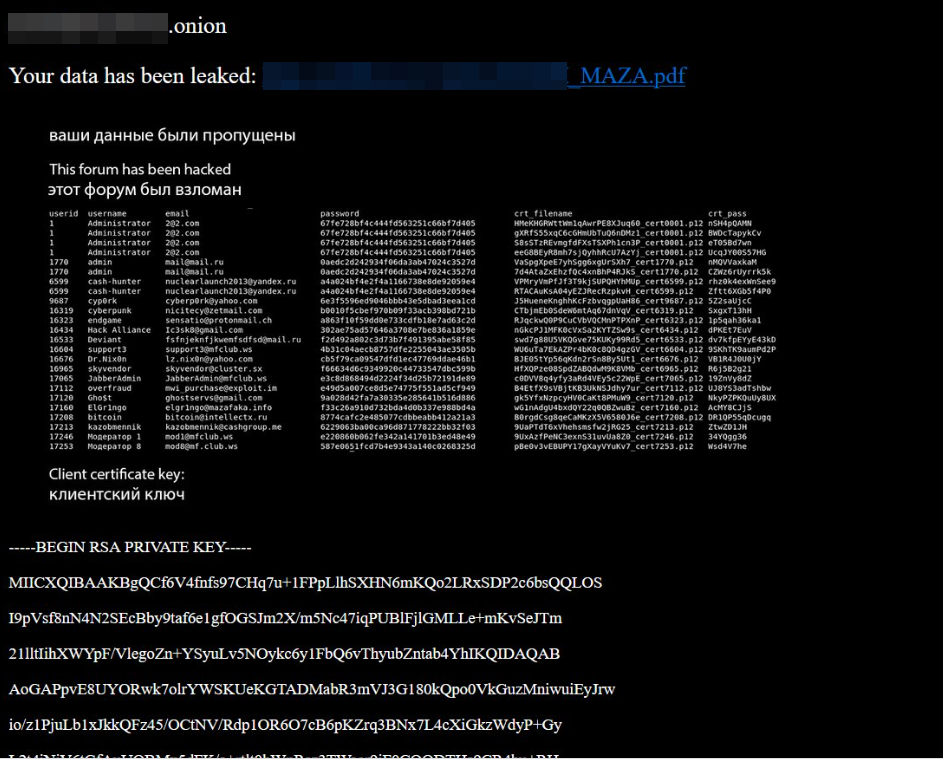

mardi 9 mars 2021 à 22:04Globally, hundreds of thousand of organizations running Exchange email servers from Microsoft just got mass-hacked, including at least 30,000 victims in the United States. Each hacked server has been retrofitted with a “web shell” backdoor that gives the bad guys total, remote control, the ability to read all email, and easy access to the victim’s other computers. Researchers are now racing to identify, alert and help victims, and hopefully prevent further mayhem.

On Mar. 5, KrebsOnSecurity broke the news that at least 30,000 organizations and hundreds of thousands globally had been hacked. The same sources who shared those figures say the victim list has grown considerably since then, with many victims compromised by multiple cybercrime groups.

Security experts are now trying to alert and assist these victims before malicious hackers launch what many refer to with a mix of dread and anticipation as “Stage 2,” when the bad guys revisit all these hacked servers and seed them with ransomware or else additional hacking tools for crawling even deeper into victim networks.

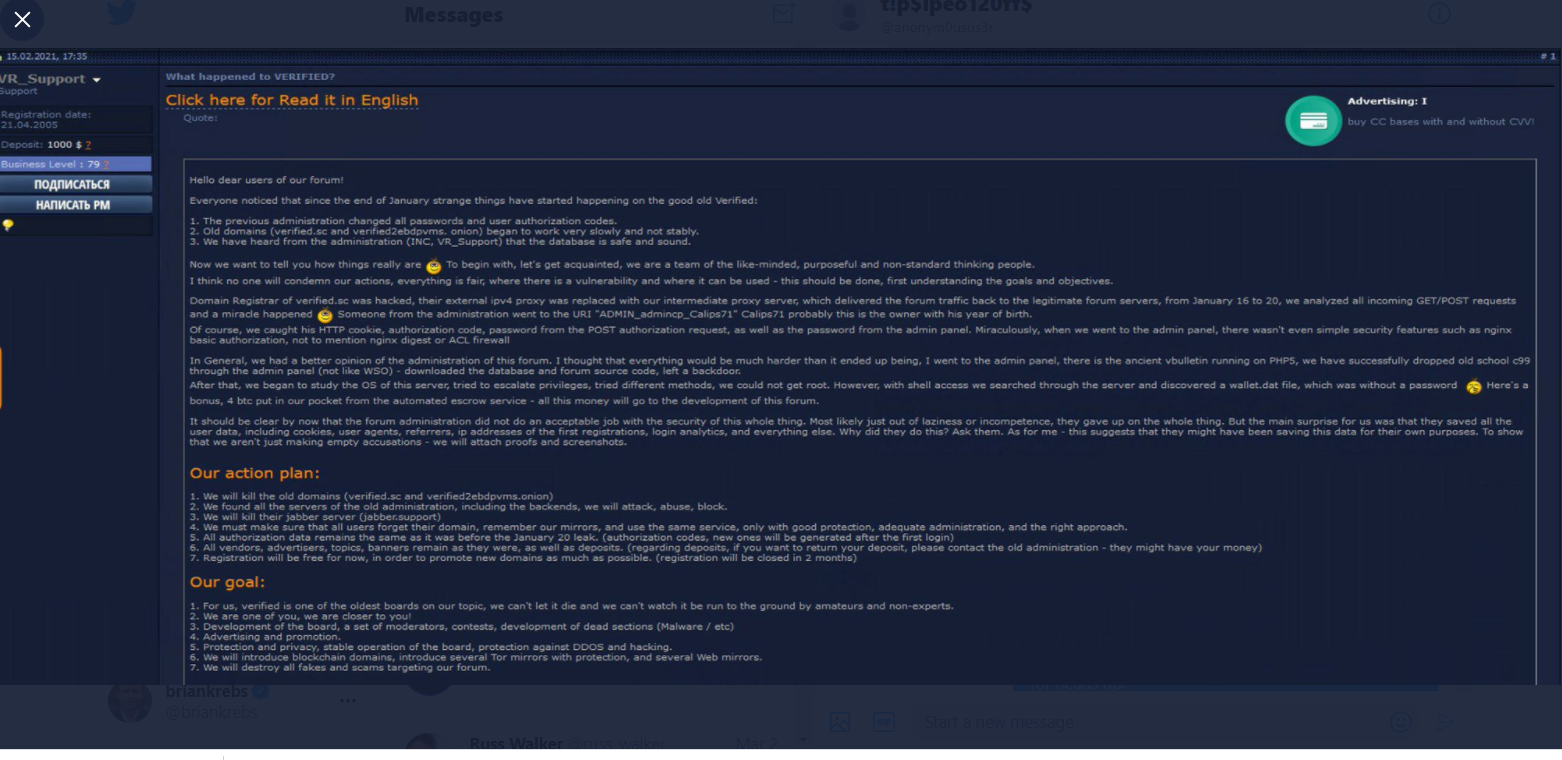

But that rescue effort has been stymied by the sheer volume of attacks on these Exchange vulnerabilities, and by the number of apparently distinct hacking groups that are vying for control over vulnerable systems.

A security expert who has briefed federal and military advisors on the threat says many victims appear to have more than one type of backdoor installed. Some victims had three of these web shells installed. One was pelted with eight distinct backdoors. This initially caused a major overcount of potential victims, and required a great deal of de-duping various victim lists.

The source, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said many in the cybersecurity community recently saw a large spike in attacks on thousands of Exchange servers that was later linked to a profit-motivated cybercriminal group.

“What we thought was Stage 2 actually was one criminal group hijacking like 10,000 exchange servers,” said one source who’s briefed U.S. national security advisors on the outbreak.

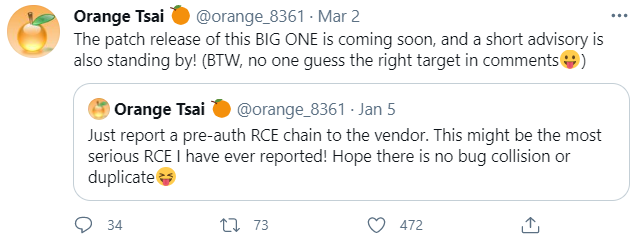

On Mar. 2, when Microsoft released updates to plug the four Exchange flaws being attacked, it attributed the hacking activity to a previously unidentified Chinese cyber espionage group it called “Hafnium.” Microsoft said Hafnium had been using the Exchange flaws to conduct a series of low-and-slow attacks against specific strategic targets, such as non-governmental organization (NGOs) and think tanks.

But by Feb. 26, that relatively stealthy activity was morphing into the indiscriminate mass-exploitation of all vulnerable Exchange servers. That means even Exchange users that patched the same day Microsoft released security updates may have had servers seeded with backdoors.

Many experts who spoke to KrebsOnSecurity said they believe different cybercriminal groups somehow learned of Microsoft’s plans to ship fixes for the Exchange flaws a week earlier than they’d hoped (Microsoft originally targeted today, Patch Tuesday, as the release date).

The vulnerability scanning activity also ramped up markedly after Microsoft released its updates on Mar. 2. Security researchers love to tear apart patches for clues about the underlying security holes, and one major concern is that various cybercriminal groups may have already worked out how to exploit the flaws independently.

AVERTING MASS-RANSOMWARE

Security experts now are desperately trying to reach tens of thousands of victim organizations with a single message: Whether you have patched yet or have been hacked, backup any data stored on those servers immediately.

Every source I’ve spoken with about this incident says they fully expect profit-motivated cybercriminals to pounce on victims by mass-deploying ransomware. Given that so many groups now have backdoor web shells installed, it would be trivial to unleash ransomware on the lot of them in one go. Also, compromised Exchange servers can be a virtual doorway into the rest of the victim’s network.

“With the number of different threat actors dropping [web] shells on servers increasing, ransomware is inevitable,” said Allison Nixon, chief research officer at Unit221B, a New York City-based cyber investigations firm.

So far there are no signs of victims of this mass-hack being ransomed. But that may well change if the exploit code used to break into these vulnerable Exchange servers goes public. And nobody I’ve interviewed seems to think working exploit code is going to stay unpublished for much longer.

When that happens, the exploits will get folded into publicly available exploit testing kits, effectively making it simple for any attacker to find and compromise a decent number of victims who haven’t already patched.

CHECK MY OWA

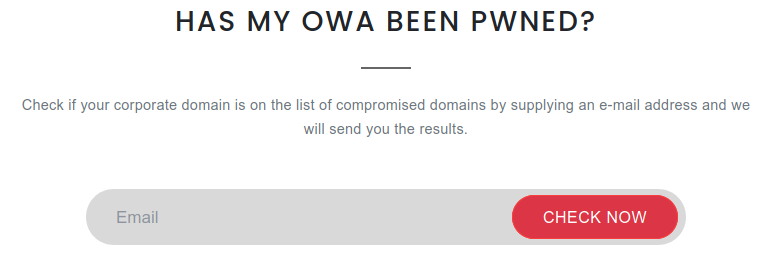

Nixon is part of a group of security industry leaders who are contributing data and time to a new victim notification platform online called Check My OWA (Outlook Web Access, the Internet-facing Web component of Exchange Server machines).

Checkmyown.unit221b.com checks if your Exchange Server domain showed up in attack logs or lists of known-compromised domains.

Perhaps it’s better to call it a self-notification service that is operated from Unit221B’s own web site. It draws on tens of thousands of data points that various ISPs and hosting firms have tied to victims around the world who are likely compromised by the backdoor shells. The data comes from large networks watching the sources and targets of mass-scans for vulnerable Exchange servers.

“Our goal is to motivate people who we might otherwise have never been able to contact,” Nixon said. “My hope is if this site can get out there, then there’s a chance some victim companies are notified and take action or can get attention.”

Enter an email address at Check My OWA, and if that address matches a domain name for a victim organization, that email address will get a notice.

If the email’s domain name (anything to the right of the @ sign) is detected in their database, the site will send that user an email stating that is has observed the email domain in a list of targeted domains.

“Malicious actors were able to successfully compromise, and some of this information suggested they may have been able to install a webshell on an Exchange server associated with this domain,” reads one of the messages to victims. “We strongly recommend saving an offline backup of your Exchange server’s emails immediately, and refer back to the site for additional information on patching and remediation.”

Other Exchange users may see this message:

“We have observed your e-mail domain appears in our list of domains the malicious actors were able to successfully compromise, and some of this information suggested they may have been able to install a webshell on an Exchange server associated with this domain,” is another message the site may return. We strongly recommend saving an offline backup of your Exchange server’s emails immediately, and refer back to the site for additional information on patching and remediation.”

Nixon said Exchange users can save themselves a potentially nightmarish scenario if they just back up any affected systems now. And given the number of adversaries currently attacking still-unpatched Exchange systems, there is almost no way this won’t end in disaster for at least some victims.

“There are researchers running honeypots to [attract] attacks from different groups, and those honeypots are getting shelled left and right,” she said. “The sooner they can run a backup, the better. This can help save a lot of heartache.”

Oh, and one more important thing: You’ll want to keep any backups disconnected from everything. Ransomware has a tendency to infect everything it can, so make sure at least one backup is stored completely offline.

“Just disconnect them from a computer, put them in a safe place and pray you don’t need them,” Nixon said.