Inside Ireland’s Public Healthcare Ransomware Scare

mardi 14 décembre 2021 à 03:13The consulting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers recently published lessons learned from the disruptive and costly ransomware attack in May 2021 on Ireland’s public health system. The unusually candid post-mortem found that nearly two months elapsed between the initial intrusion and the launching of the ransomware. It also found affected hospitals had tens of thousands of outdated Windows 7 systems, and that the health system’s IT administrators failed to respond to multiple warning signs that a massive attack was imminent.

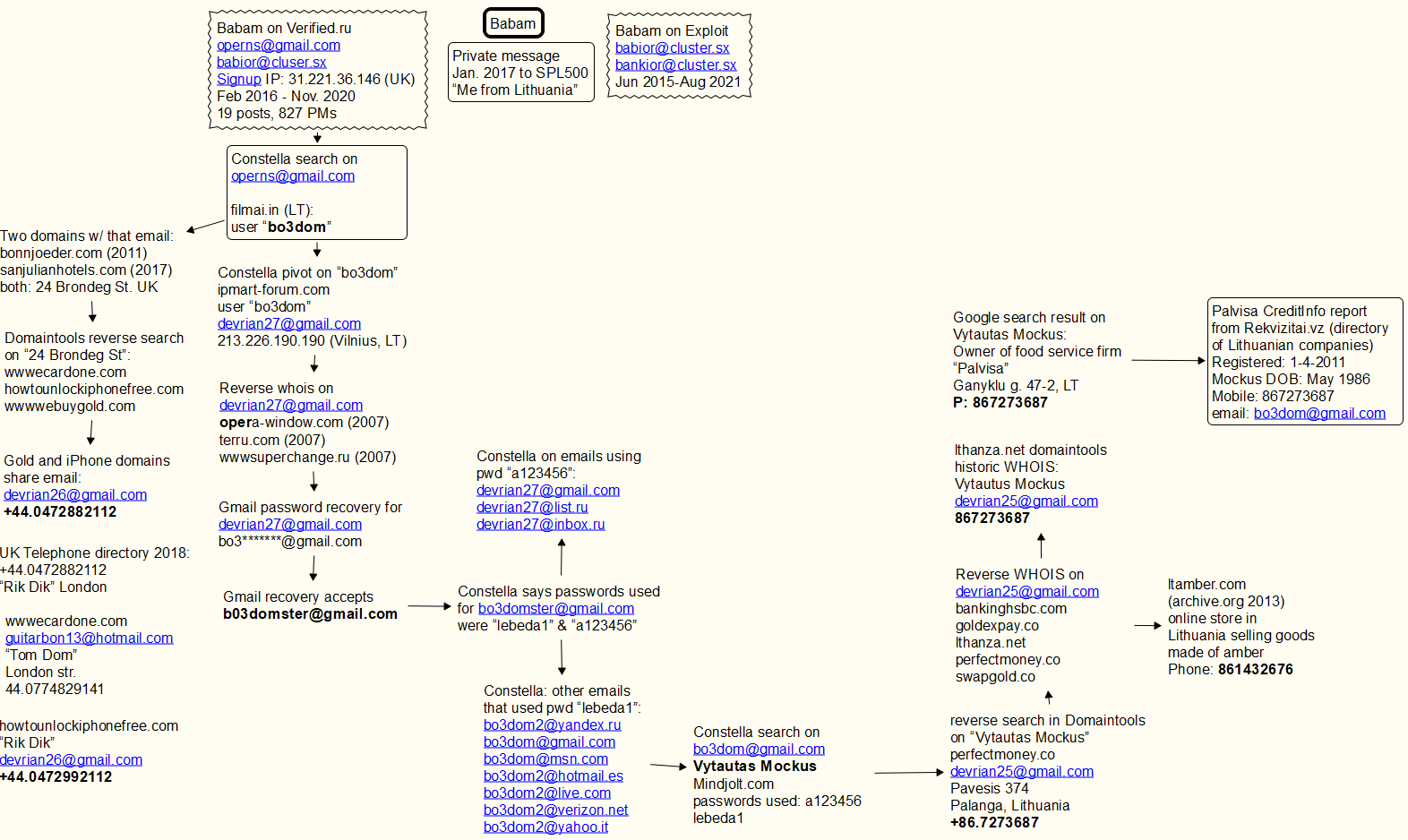

PWC’s timeline of the days leading up to the deployment of Conti ransomware on May 14.

Ireland’s Health Service Executive (HSE), which operates the country’s public health system, got hit with Conti ransomware on May 14, 2021. A timeline in the report (above) says the initial infection of the “patient zero” workstation happened on Mar. 18, 2021, when an employee on a Windows computer opened a booby-trapped Microsoft Excel document in a phishing email that had been sent two days earlier.

Less than a week later, the attacker had established a reliable backdoor connection to the employee’s infected workstation. After infecting the system, “the attacker continued to operate in the environment over an eight week period until the detonation of the Conti ransomware on May 14, 2021,” the report states.

According to PWC’s report (PDF), there were multiple warning signs about a serious network intrusion, but those red flags were either misidentified or not acted on quickly enough:

- On Mar. 31, 2021, the HSE’s antivirus software detected the execution of two software tools commonly used by ransomware groups — Cobalt Strike and Mimikatz — on the Patient Zero Workstation. But the antivirus software was set to monitor mode, so it did not block the malicious commands.”

- On May 7, the attacker compromised the HSE’s servers for the first time, and over the next five days the intruder would compromise six HSE hospitals. On May 10, one of the hospitals detected malicious activity on its Microsoft Windows Domain Controller, a critical “keys to the kingdom” component of any Windows enterprise network that manages user authentication and network access.

- On 10 May 2021, security auditors first identified evidence of the attacker compromising systems within Hospital C and Hospital L. Hospital C’s antivirus software detected Cobalt Strike on two systems but failed to quarantine the malicious files.

- On May 13, the HSE’s antivirus security provider emailed the HSE’s security operations team, highlighting unhandled threat events dating back to May 7 on at least 16 systems. The HSE Security Operations team requested that the Server team restart servers.

By then it was too late. At just after midnight Ireland time on May 14, the attacker executed the Conti ransomware within the HSE. The attack disrupted services at several Irish hospitals and resulted in the near complete shutdown of the HSE’s national and local networks, forcing the cancellation of many outpatient clinics and healthcare services. The number of appointments in some areas dropped by up to 80 percent.”

Conti initially demanded USD $20 million worth of virtual currency in exchange for a digital key to unlock HSE servers compromised by the group. But perhaps in response to the public outcry over the HSE disruption, Conti reversed course and gave the HSE the decryption keys without requiring payment.

Still, the work to restore infected systems would take months. The HSE ultimately enlisted members of the Irish military to bring in laptops and PCs to help restore computer systems by hand. It wasn’t until September 21, 2021 that the HSE declared 100 percent of its servers were decrypted.

As bad as the HSE ransomware attack was, the PWC report emphasizes that it could have been far worse. For example, it is unclear how much data would have been unrecoverable if a decryption key had not become available as the HSE’s backup infrastructure was only periodically backed up to offline tape.

The attack also could have been worse, the report found:

- if there had been intent by the Attacker to target specific devices within the HSE environment (e.g. medical devices);

- if the ransomware took actions to destroy data at scale;

- if the ransomware had auto-propagation and persistence capabilities, for example by using an exploit to propagate across domains and trust-boundaries to medical devices (e.g. the EternalBlue exploit used by the WannaCry and NotPetya15 attacks);

- if cloud systems had also been encrypted such as the COVID-19 vaccination system

The PWC report contains numerous recommendations, most of which center around hiring new personnel to lead the organization’s redoubled security efforts. But it is clear that the HSE has an enormous amount of work ahead to grow in security maturity. For example, the report notes the HSE’s hospital network had over 30,000 Windows 7 workstations that were deemed end of life by the vendor.

“The HSE assessed its cybersecurity maturity rating as low,” PWC wrote. “For example, they do not have a CISO or a Security Operations Center established.”

PWC also estimates that efforts to build up the HSE’s cybersecurity program to the point where it can rapidly detect and respond to intrusions are likely to cost “a multiple of the HSE’s current capital and operation expenditure in these areas over several years.”

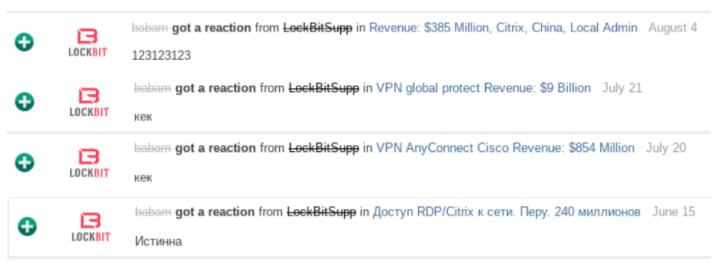

One idea of a “security maturity” model.

In June 2021, the HSE’s director general said the recovery costs for the May ransomware attack were likely to exceed USD $600 million.

What’s remarkable about this incident is that the HSE is publicly funded by the Irish government, and so in theory it has the money to spend (or raise) to pay for all these ambitious recommendations for increasing their security maturity.

That stands in stark contrast to the healthcare system here in the United States, where the single biggest impediment to doing security well continues to be lack of making it a real budget priority. Also, most healthcare organizations in the United States are private companies that operate on razor-thin profit margins.

I know this because in 2018 I was asked to give the keynote at an annual gathering of the Healthcare Information Sharing and Analysis Group (H-ISAC), an industry group centered on sharing information about cybersecurity threats. I almost didn’t accept the invitation: I’d written very little about healthcare security, which seemed to be dominated by coverage of whether healthcare organizations complied with the letter of the law in the United States. That compliance centered on the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA), which prioritizes protecting the integrity and privacy of patient data.

To get up to speed, I interviewed over a dozen of the healthcare security industry’s best and brightest minds. A common refrain I heard from those interviewed was that if it was security-related but didn’t have to do with compliance, there probably wasn’t much chance it would get any budget.

Those sources unanimously said that however well-intentioned, it’s not clear that the “protect the data” regulatory approach of HIPPA was working from an overall threat perspective. According to HealthcareIT News, more than 40 million patient records have been compromised in incidents reported to the federal government in 2021 so far alone.

During my 2018 talk, I tried to emphasize the primary importance of being able to respond quickly to intrusions. Here’s a snippet of what I told that H-ISAC audience:

“The term ‘Security Maturity’ refers to the street smarts of an individual or organization, and this maturity generally comes from making plenty of mistakes, getting hacked a lot, and hopefully learning from each incident, measuring response times, and improving.

Let me say up front that all organizations get hacked. Even ones that are doing everything right from a security perspective get hacked probably every day if they’re big enough. By hacked I mean someone within the organization falls for a phishing scam, or clicks a malicious link and downloads malware. Because let’s face it, it only takes one screw up for the hackers to get a foothold in the network.

Now this is in itself isn’t bad. Unless you don’t have the capability to detect it and respond quickly. And if you can’t do that, you run the serious risk of having a small incident metastasize into a much larger problem.

Think of it like the medical concept of the ‘Golden Hour:’ That short window of time directly following a traumatic injury like a stroke or heart attack in which life-saving medicine and attention is likely to be most effective. The same concept holds true in cybersecurity, and it’s exactly why so many organizations these days are placing more of their resources into incident response, instead of just prevention.”

The United States’ somewhat decentralized healthcare system means that many ransomware outbreaks tend to be limited to regional or local healthcare facilities. But a well-placed ransomware attack or series of attacks could inflict serious damage on the sector: A December 2020 report from Deloitte says the top 10 health systems now control 24 market share and their revenue grew at twice the rate of the rest of the market.

In October 2020, KrebsOnSecurity broke the story that the FBI and U.S. Department of Homeland Security had obtained chatter from a top ransomware group which warned of an “imminent cybercrime threat to U.S. hospitals and healthcare providers.” Members associated with the Russian-speaking ransomware group known as Ryuk had discussed plans to deploy ransomware at more than 400 healthcare facilities in the United States.

Hours after that piece ran, I head from a respected H-ISAC security professional who questioned whether it was worth getting the public so riled up. The story had been updated multiple times throughout the day, and there were at least five healthcare organizations hit with ransomware within the span of 24 hours.

“I guess it would help if I understood what the baseline is, like how many healthcare organizations get hit with ransomware on average in one week?” I asked the source.

“It’s more like one a day,” the source confided.

In all likelihood, the HSE will get the money it needs to implement the programs recommended by PWC, however long that takes. I wonder how many U.S.-based healthcare organizations could say the same.