Companies around the globe are scrambling to comply with new European privacy regulations that take effect a little more than three months from now. But many security experts are worried that the changes being ushered in by the rush to adhere to the law may make it more difficult to track down cybercriminals and less likely that organizations will be willing to share data about new online threats.

On May 25, 2018, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) takes effect. The law, enacted by the European Parliament, requires technology companies to get affirmative consent for any information they collect on people within the European Union. Organizations that violate the GDPR could face fines of up to four percent of global annual revenues.

In response, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICAAN) — the nonprofit entity that manages the global domain name system — is poised to propose changes to the rules governing how much personal information Web site name registrars can collect and who should have access to the data.

Specifically, ICANN has been seeking feedback on a range of proposals to redact information provided in WHOIS, the system for querying databases that store the registered users of domain names and blocks of Internet address ranges (IP addresses).

Under current ICANN rules, domain name registrars should collect and display a variety of data points when someone performs a WHOIS lookup on a given domain, such as the registrant’s name, address, email address and phone number. (Most registrars offer a privacy protection service that shields this information from public WHOIS lookups; some registrars charge a nominal fee for this service, while others offer it for free).

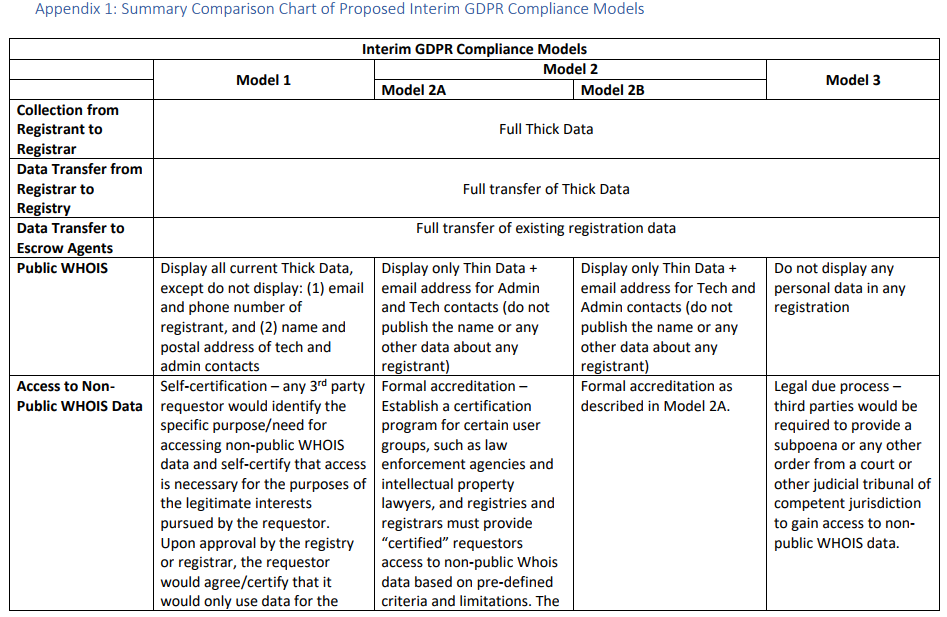

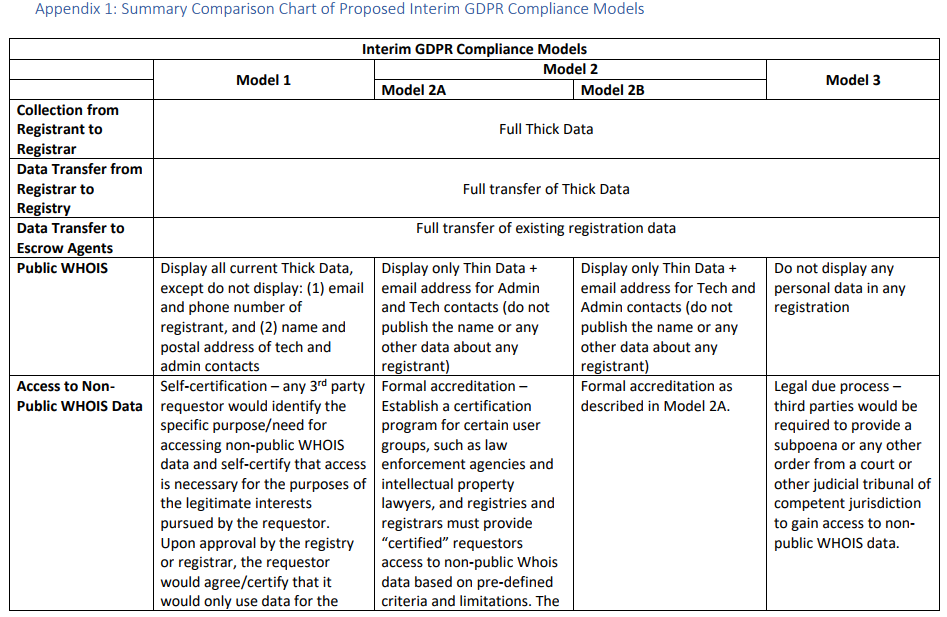

In a bid to help domain registrars comply with the GDPR regulations, ICANN has floated several proposals, all of which would redact some of the registrant data from WHOIS records. Its mildest proposal would remove the registrant’s name, email, and phone number, while allowing self-certified 3rd parties to request access to said data at the approval of a higher authority — such as the registrar used to register the domain name.

The most restrictive proposal would remove all registrant data from public WHOIS records, and would require legal due process (such as a subpoena or court order) to reveal any information supplied by the domain registrant.

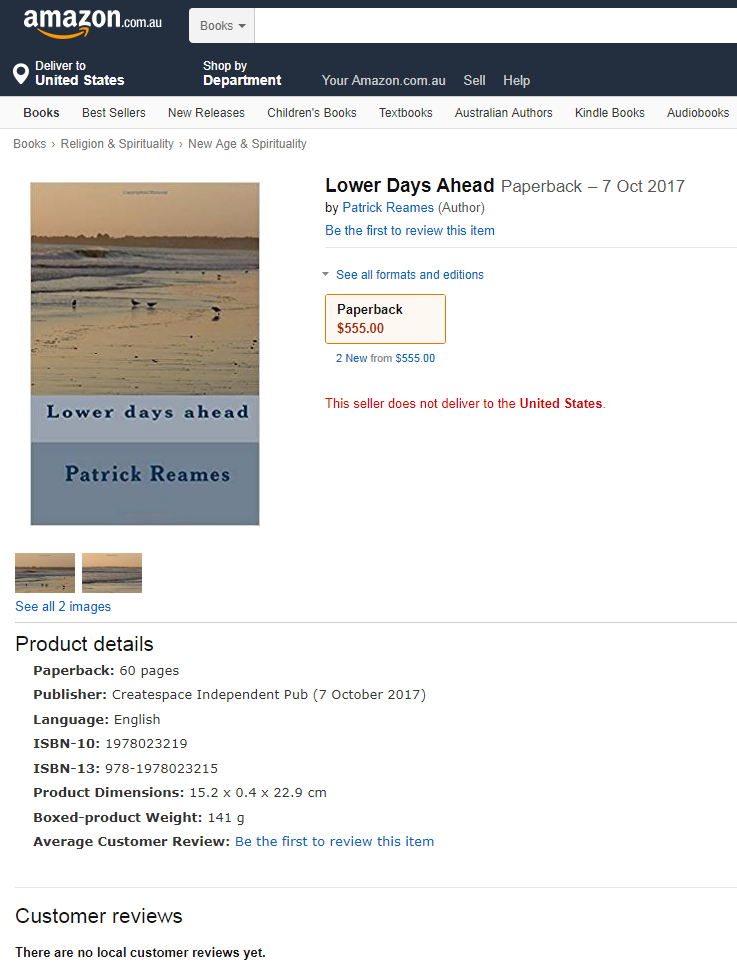

ICANN’s various proposed models for redacting information in WHOIS domain name records.

The full text of ICANN’s latest proposed models (from which the screenshot above was taken) can be found here (PDF). A diverse ICANN working group made up of privacy activists, technologists, lawyers, trademark holders and security experts has been arguing about these details since 2016. For the curious and/or intrepid, the entire archive of those debates up to the current day is available at this link.

WHAT IS THE WHOIS DEBATE?

To drastically simplify the discussions into two sides, those in the privacy camp say WHOIS records are being routinely plundered and abused by all manner of ne’er-do-wells, including spammers, scammers, phishers and stalkers. In short, their view seems to be that the availability of registrant data in the WHOIS records causes more problems than it is designed to solve.

Meanwhile, security experts are arguing that the data in WHOIS records has been indispensable in tracking down and bringing to justice those who seek to perpetrate said scams, spams, phishes and….er….stalks.

Many privacy advocates seem to take a dim view of any ICANN system by which third parties (and not just law enforcement officials) might be vetted or accredited to look at a domain registrant’s name, address, phone number, email address, etc. This sentiment is captured in public comments made by the Electronic Frontier Foundation‘s Jeremy Malcolm, who argued that — even if such information were only limited to anti-abuse professionals — this also wouldn’t work.

“There would be nothing to stop malicious actors from identifying as anti-abuse professionals – neither would want to have a system to ‘vet’ anti-abuse professionals, because that would be even more problematic,” Malcolm wrote in October 2017. “There is no added value in collecting personal information – after all, criminals are not going to provide correct information anyway, and if a domain has been compromised then the personal information of the original registrant isn’t going to help much, and its availability in the wild could cause significant harm to the registrant.”

Anti-abuse and security experts counter that there are endless examples of people involved in spam, phishing, malware attacks and other forms of cybercrime who include details in WHOIS records that are extremely useful for tracking down the perpetrators, disrupting their operations, or building reputation-based systems (such as anti-spam and anti-malware services) that seek to filter or block such activity.

Moreover, they point out that the overwhelming majority of phishing is performed with the help of compromised domains, and that the primary method for cleaning up those compromises is using WHOIS data to contact the victim and/or their hosting provider.

Many commentators observed that, in the end, ICANN is likely to proceed in a way that covers its own backside, and that of its primary constituency — domain registrars. Registrars pay a fee to ICANN for each domain a customer registers, although revenue from those fees has been falling of late, forcing ICANN to make significant budget cuts.

Some critics of the WHOIS privacy effort have voiced the opinion that the registrars generally view public WHOIS data as a nuisance issue for their domain registrant customers and an unwelcome cost-center (from being short-staffed to field a constant stream of abuse complaints from security experts, researchers and others in the anti-abuse community).

“Much of the registrar market is a race to the bottom, and the ability of ICANN to police the contractual relationships in that market effectively has not been well-demonstrated over time,” commenter Andrew Sullivan observed.

In any case, sources close to the debate tell KrebsOnSecurity that ICANN is poised to recommend a WHOIS model loosely based on Model 1 in the chart above.

Specifically, the system that ICANN is planning to recommend, according to sources, would ask registrars and registries to display just the domain name, city, state/province and country of the registrant in each record; the public email addresses would be replaced by a form or message relay link that allows users to contact the registrant. The source also said ICANN plans to leave it up to the registries/registrars to apply these changes globally or only to natural persons living in the European Economic Area (EEA).

In addition, sources say non-public WHOIS data would be accessible via a credentialing system to identify law enforcement agencies and intellectual property rights holders. However, it’s unlikely that such a system would be built and approved before the May 25, 2018 effectiveness date for the GDPR, so the rumor is that ICANN intends to propose a self-certification model in the meantime.

ICANN spokesman Brad White declined to confirm or deny any of the above, referring me instead to a blog post published Tuesday evening by ICANN CEO Göran Marby. That post does not, however, clarify which way ICANN may be leaning on the matter.

“Our conversations and work are on-going and not yet final,” White wrote in a statement shared with KrebsOnSecurity. “We are converging on a final interim model as we continue to engage, review and assess the input we receive from our stakeholders and Data Protection Authorities (PDAs).”

But with the GDPR compliance deadline looming, some registrars are moving forward with their own plans on WHOIS privacy. GoDaddy, one of the world’s largest domain registrars, recently began redacting most registrant data from WHOIS records for domains that are queried via third-party tools. And it seems likely that other registrars will follow GoDaddy’s lead.

ANALYSIS

For my part, I can say without hesitation that few resources are as critical to what I do here at KrebsOnSecurity than the data available in the public WHOIS records. WHOIS records are incredibly useful signposts for tracking cybercrime, and they frequently allow KrebsOnSecurity to break important stories about the connections between and identities behind various cybercriminal operations and the individuals/networks actively supporting or enabling those activities. I also very often rely on WHOIS records to locate contact information for potential sources or cybercrime victims who may not yet be aware of their victimization.

In a great many cases, I have found that clues about the identities of those who perpetrate cybercrime can be found by following a trail of information in WHOIS records that predates their cybercriminal careers. Also, even in cases where online abusers provide intentionally misleading or false information in WHOIS records, that information is still extremely useful in mapping the extent of their malware, phishing and scamming operations.

Anyone looking for copious examples of both need only to search this Web site for the term “WHOIS,” which yields dozens of stories and investigations that simply would not have been possible without the data currently available in the global WHOIS records.

Many privacy activists involved in to the WHOIS debate have argued that other data related to domain and Internet address registrations — such as name servers, Internet (IP) addresses and registration dates — should also be considered private information. My chief concern if this belief becomes more widely held is that security companies might stop sharing such information for fear of violating the GDPR, thus hampering the important work of anti-abuse and security professionals.

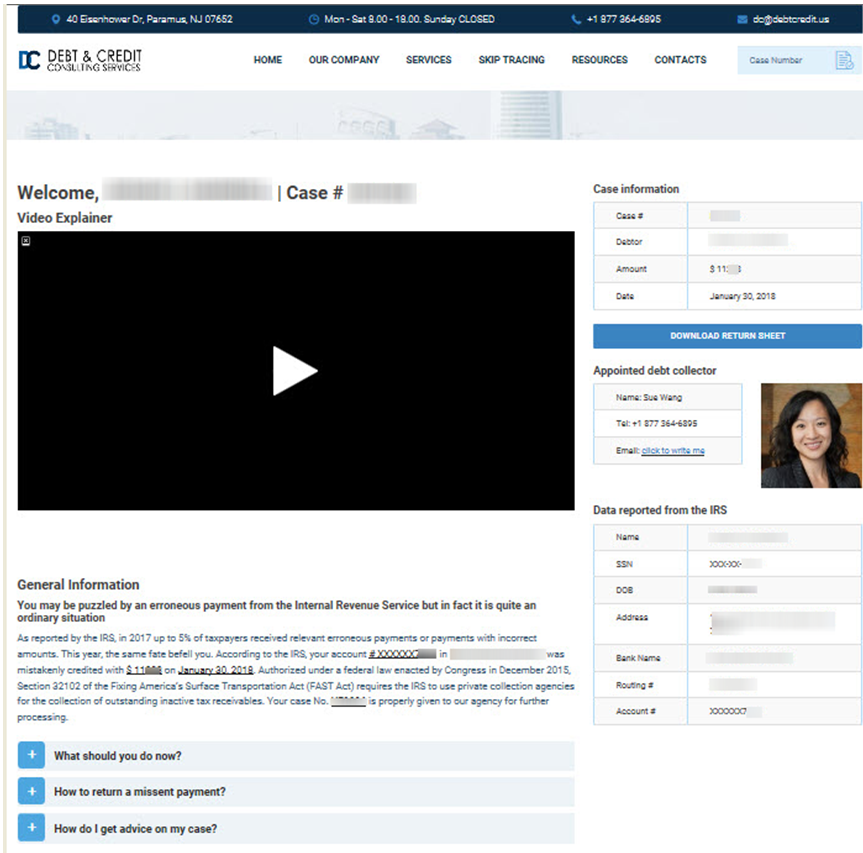

This is hardly a theoretical concern. Last month I heard from a security firm based in the European Union regarding a new Internet of Things (IoT) botnet they’d discovered that was unusually complex and advanced. Their outreach piqued my curiosity because I had already been working with a researcher here in the United States who was investigating a similar-sounding IoT botnet, and I wanted to know if my source and the security company were looking at the same thing.

But when I asked the security firm to share a list of Internet addresses related to their discovery, they told me they could not do so because IP addresses could be considered private data — even after I assured them I did not intend to publish the data.

“According to many forums, IPs should be considered personal data as it enters the scope of ‘online identifiers’,” the researcher wrote in an email to KrebsOnSecurity, declining to answer questions about whether their concern was related to provisions in the GDPR specifically. “Either way, it’s IP addresses belonging to people with vulnerable/infected devices and sharing them may be perceived as bad practice on our end. We consider the list of IPs with infected victims to be private information at this point.”

Certainly as the Internet matures and big companies develop ever more intrusive ways to hoover up data on consumers, we also need to rein in the most egregious practices while giving Internet users more robust tools to protect and preserve their privacy. In the context of Internet security and the privacy principles envisioned in the GDPR, however, I’m worried that cybercriminals may end up being the biggest beneficiaries of this new law.