‘ValidCC,’ a Major Payment Card Bazaar and Looter of E-Commerce Sites, Shuttered

mardi 2 février 2021 à 19:04ValidCC, a dark web bazaar run by a cybercrime group that for more than six years hacked online merchants and sold stolen payment card data, abruptly closed up shop last week. The proprietors of the popular store said their servers were seized as part of a coordinated law enforcement operation designed to disconnect and confiscate its infrastructure.

ValidCC, circa 2017.

There are dozens of online shops that sell so-called “card not present” (CNP) payment card data stolen from e-commerce stores, but most source the data from other criminals. In contrast, researchers say ValidCC was actively involved in hacking and pillaging hundreds of online merchants — seeding the sites with hidden card-skimming code that siphoned personal and financial information as customers went through the checkout process.

Russian cybersecurity firm Group-IB published a report last year detailing the activities of ValidCC, noting the gang behind the crime shop was responsible for plundering nearly 700 e-commerce sites. Group-IB dubbed the gang “UltraRank,” which it said had additionally compromised at least 13 third-party suppliers whose software components are used by countless online stores across Europe, Asia, North and Latin America.

Group-IB believes UltraRank is responsible for a slew of hacks that other security firms previously attributed to at least three distinct cybercrime groups.

“Over five years….UltraRank changed its infrastructure and malicious code on numerous occasions, as a result of which cybersecurity experts would wrongly attribute its attacks to other threat actors,” Group-IB wrote. “UltraRank combined attacks on single targets with supply chain attacks.”

ValidCC’s front man on multiple forums — a cybercriminal who uses the hacker handle “SPR” — told customers on Jan. 28 that the shop would close for good following what appeared to be a law enforcement takedown of its operations. SPR claims his site lost access to a significant inventory — more than 600,000 unsold stolen payment card accounts.

“As a result, we lost the proxy and destination backup servers,” SPR explained. “Besides, now it’s impossible to open and decrypt the backend. The database is in the hands of the police, but it’s encrypted.”

ValidCC had thousands of users, some of whom held significant balances of bitcoin stored in the shop when it ceased operations. SPR claims the site took in approximately $100,000 worth of virtual currency deposits each day from customers.

Many of those customers took to the various crime forums where the shop has a presence to voice suspicions that the proprietors had simply decided to walk away with their money at a time when Bitcoin was near record-high price levels.

SPR countered that ValidCC couldn’t return balances because it no longer had access to its own ledgers.

“We don’t know anything!,” SPR pleaded. “We don’t know users’ balances, or your account logins or passwords, or the [credit cards] you purchased, or anything else! You are free to think what you want, but our team has never conned or let anyone down since the beginning of our operations! Nobody would abandon a dairy cow and let it die in the field! We did not take this decision lightly!”

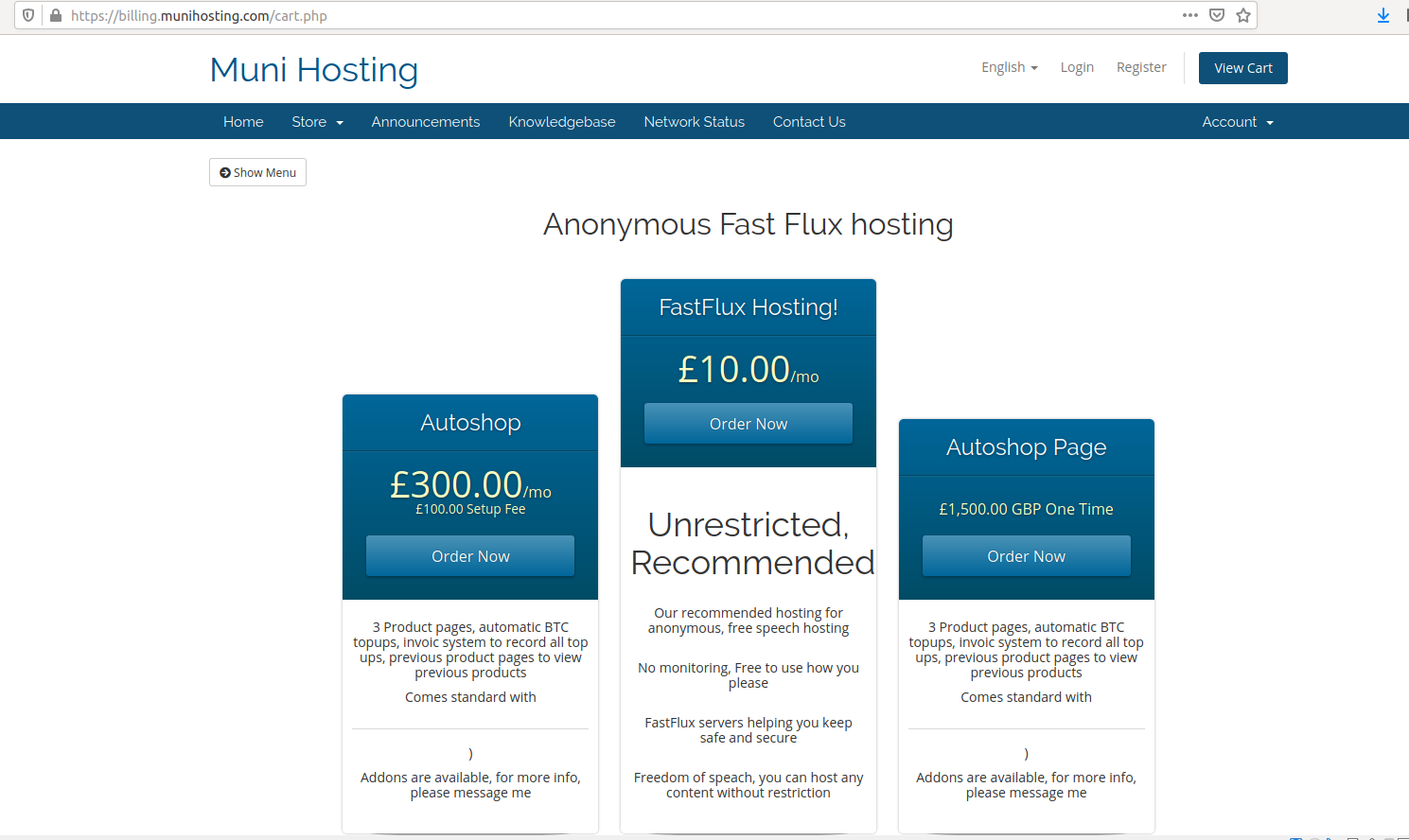

Group-IB said ValidCC was one of many cybercrime shops that stored some or all of its operational components at Media Land LLC, a major “bulletproof hosting” provider that supports a vast array of phishing sites, cybercrime forums and malware download servers.

Assuming SPR’s claims are truthful, it could be that law enforcement agencies targeted portions of Media Land’s digital infrastructure in some sort of coordinated action. However, so far there are no signs of any major uproar in the cybercrime underground directed at Yalishanda, the nickname used by the longtime proprietor of Media Land.

ValidCC’s demise comes close on the heels of the shuttering of Joker’s Stash, by some accounts the largest underground shop for selling stolen credit card and identity data. On Dec. 16, 2020, several of Joker’s long-held domains began displaying notices that the sites had been seized by the U.S. Department of Justice and Interpol. Less than a month later, Joker announced he was closing the shop permanently.

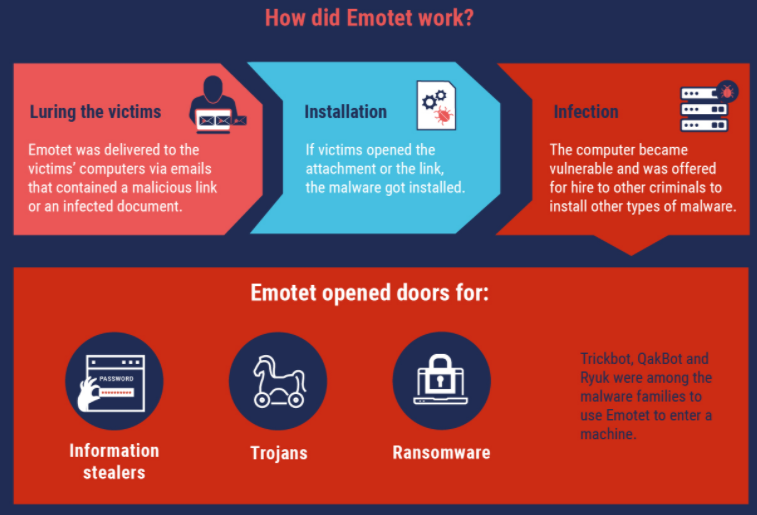

And last week, authorities across Europe seized control over dozens of servers used to operate Emotet, a prolific malware strain and cybercrime-as-service operation. While there are no indications that action targeted any criminal groups apart from the Emotet gang, it is often the case that multiple cybercrime groups will share the same dodgy digital infrastructure providers, knowingly or unwittingly.

Gemini Advisory, a New York-based firm that closely monitors cybercriminal stores, said ValidCC’s administrators recently began recruiting stolen card data resellers who previously had sold their wares to Joker’s Stash.

Stas Alforov, Gemini’s director of research and development, said other card shops will quickly move in to capture the customers and suppliers who frequented ValidCC.

“There are still a bunch of other shops out there,” Alforov said. “There’s enough tier one shops out there that sell card-not-present data that haven’t dropped a beat and have even picked up volumes.”

One state’s experience offers a window into the potential scope of the problem. Hackers, identity thieves and overseas criminal rings stole over $11 billion in unemployment benefits from California last year, or roughly 10 percent of all such claims the state paid out in 2020, the state’s labor secretary

One state’s experience offers a window into the potential scope of the problem. Hackers, identity thieves and overseas criminal rings stole over $11 billion in unemployment benefits from California last year, or roughly 10 percent of all such claims the state paid out in 2020, the state’s labor secretary