Voice Phishing Scams Are Getting More Clever

lundi 1 octobre 2018 à 16:02Most of us have been trained to be wary of clicking on links and attachments that arrive in emails unexpected, but it’s easy to forget scam artists are constantly dreaming up innovations that put a new shine on old-fashioned telephone-based phishing scams. Think you’re too smart to fall for one? Think again: Even technology experts are getting taken in by some of the more recent schemes (or very nearly).

Matt Haughey is the creator of the community Weblog MetaFilter and a writer at Slack. Haughey banks at a small Portland credit union, and last week he got a call on his mobile phone from an 800-number that matched the number his credit union uses.

Actually, he got three calls from the same number in rapid succession. He ignored the first two, letting them both go to voicemail. But he picked up on the third call, thinking it must be something urgent and important. After all, his credit union had rarely ever called him.

Haughey said he was greeted by a female voice who explained that the credit union had blocked two phony-looking charges in Ohio made to his debit/ATM card. She proceeded to then read him the last four digits of the card that was currently in his wallet. It checked out.

Haughey told the lady that he would need a replacement card immediately because he was about to travel out of state to California. Without missing a beat, the caller said he could keep his card and that the credit union would simply block any future charges that weren’t made in either Oregon or California.

This struck Haughey as a bit off. Why would the bank say they were freezing his card but then say they could keep it open for his upcoming trip? It was the first time the voice inside his head spoke up and said, “Something isn’t right, Matt.” But, he figured, the customer service person at the credit union was trying to be helpful: She was doing him a favor, he reasoned.

The caller then read his entire home address to double check it was the correct destination to send a new card at the conclusion of his trip. Then the caller said she needed to verify his mother’s maiden name. The voice in his head spoke out in protest again, but then banks had asked for this in the past. He provided it.

Next she asked him to verify the three digit security code printed on the back of his card. Once more, the voice of caution in his brain was silenced: He’d given this code out previously in the few times he’d used his card to pay for something over the phone.

Then she asked him for his current card PIN, just so she could apply that same PIN to the new card being mailed out, she assured him. Ding, ding, ding went the alarm bells in his head. Haughey hesitated, then asked the lady to repeat the question. When she did, he gave her the PIN, and she assured him she’d make sure his existing PIN also served as the PIN for his new card.

Haughey said after hanging up he felt fairly certain the entire transaction was legitimate, although the part about her requesting the PIN kept nagging at him.

“I balked at challenging her because everything lined up,” he said in an interview with KrebsOnSecurity. “But when I hung up the phone and told a friend about it, he was like, ‘Oh man, you just got scammed, there’s no way that’s real.'”

Now more concerned, Haughey visited his credit union to make sure his travel arrangements were set. When he began telling the bank employee what had transpired, he could tell by the look on her face that his friend was right.

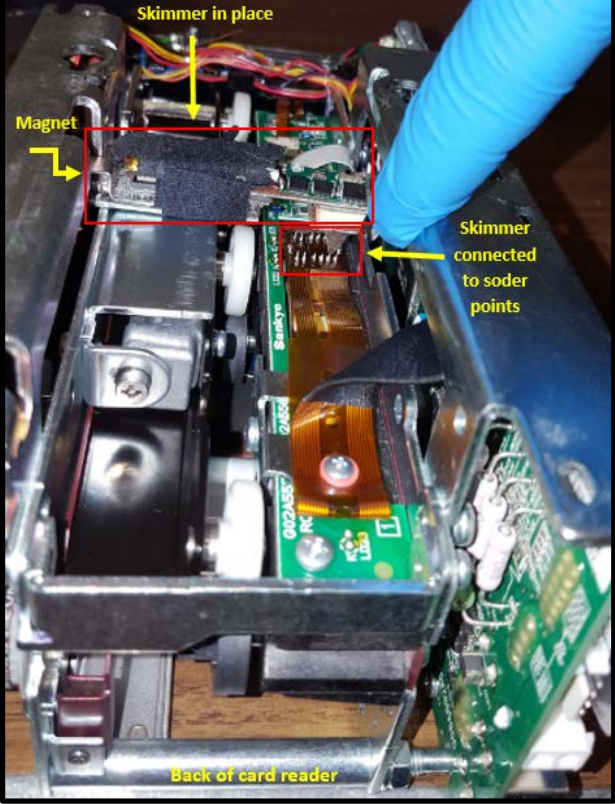

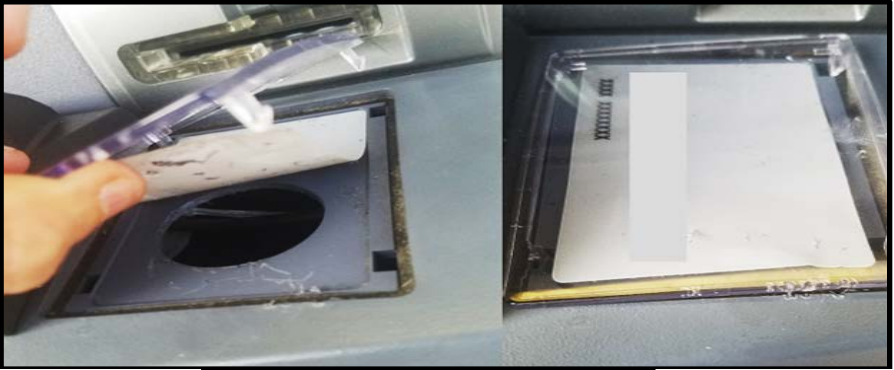

A review of his account showed that there were indeed two fraudulent charges on his account from earlier that day totaling $3,400, but neither charge was from Ohio. Rather, someone used a counterfeit copy of his debit card to spend more than $2,900 at a Kroger near Atlanta, and to withdraw almost $500 from an ATM in the same area. After the unauthorized charges, he had just $300 remaining in his account.

“People I’ve talked to about this say there’s no way they’d fall for that, but when someone from a trustworthy number calls, says they’re from your small town bank, and sounds incredibly professional, you’d fall for it, too,” Haughey said.

Fraudsters can use a variety of open-source and free tools to fake or “spoof” the number displayed as the caller ID, lending legitimacy to phone phishing schemes. Often, just sprinkling in a little foreknowledge of the target’s personal details — SSNs, dates of birth, addresses and other information that can be purchased for a nominal fee from any one of several underground sites that sell such data — adds enough detail to the call to make it seem legitimate.

A CLOSE CALL

Cabel Sasser is founder of a Mac and iOS software company called Panic Inc. Sasser said he almost got scammed recently after receiving a call that appeared to be the same number as the one displayed on the back of his Wells Fargo ATM card.

“I answered, and a Fraud Department agent said my ATM card has just been used at a Target in Minnesota, was I on vacation?” Sasser recalled in a tweet about the experience.

What Sasser didn’t mention in his tweet was that his corporate debit card had just been hit with two instances of fraud: Someone had charged $10,000 worth of metal air ducts to his card. When he disputed the charge, his bank sent a replacement card.

“I used the new card at maybe four places and immediately another fraud charge popped up for like $20,000 in custom bathtubs,” Sasser recalled in an interview with KrebsOnSecurity. “The morning this scam call came in I was spending time trying to figure out who might have lost our card data and was already in that frame of mind when I got the call about fraud on my card.”

“I used the new card at maybe four places and immediately another fraud charge popped up for like $20,000 in custom bathtubs,” Sasser recalled in an interview with KrebsOnSecurity. “The morning this scam call came in I was spending time trying to figure out who might have lost our card data and was already in that frame of mind when I got the call about fraud on my card.”

And so the card-replacement dance began.

“Is the card in your possession?,” the caller asked. It was. The agent then asked him to read the three-digit CVV code printed on the back of his card.

After verifying the CVV, the agent offered to expedite a replacement, Sasser said. “First he had to read some disclosures. Then he asked me to key in a new PIN. I picked a random PIN and entered it. Verified it again. Then he asked me to key in my current PIN.”

That made Sasser pause. Wouldn’t an actual representative from Wells Fargo’s fraud division already have access to his current PIN?

“It’s just to confirm the change,” the caller told him. “I can’t see what you enter.”

“But…you’re the bank,” he countered. “You have my PIN, and you can see what I enter…”

The caller had a snappy reply for this retort as well.

“Only the IVR [interactive voice response] system can see it,” the caller assured him. “Hey, if it helps, I have all of your account info up…to confirm, the last four digits of your Social Security number are XXXX, right?”

Sure enough, that was correct. But something still seemed off. At this point, Sasser said he told the agent he would call back by dialing the number printed on his ATM card — the same number his mobile phone was already displaying as the source of the call. After doing just that, the representative who answered said there had been no such fraud detected on his account.

“I was just four key presses away from having all my cash drained by someone at an ATM,” Sasser recalled. A visit to the local Wells Fargo branch before his trip confirmed that he’d dodged a bullet.

“The Wells person was super surprised that I bailed out when I did, and said most people are 100 percent taken by this scam,” Sasser said.

HUMAN, ROBOT OR HYBRID?

In Sasser’s case, the scammer was a live person, but some equally convincing voice phishing schemes — sometimes called “vishing” — use a combination of humans and automation. Consider the following vishing attempt, reported to KrebsOnSecurity in August by “Curt,” a longtime reader from Canada.

“I’m both a TD customer and Rogers phone subscriber and just experienced what I consider a very convincing and/or elaborate social engineering/vishing attempt,” Curt wrote. “At 7:46pm I received a call from (647-475-1636) purporting to be from Credit Alert (alertservice.ca) on behalf of TD Canada Trust offering me a free 30-day trial for a credit monitoring service.”

The caller said her name was Jen Hansen, and began the call with what Curt described as “over-the-top courtesy.”

“It sounded like a very well-scripted Customer Service call, where they seem to be trying so hard to please that it seems disingenuous,” Curt recalled. “But honestly it still sounded very much like a real person, not like a text to speech voice which sounds robotic. This sounded VERY natural.”

Ms. Hansen proceeded to tell Curt that TD Bank was offering a credit monitoring service free for one month, and that he could cancel at any time. To enroll, he only needed to confirm his home mailing address.

“I’m mega paranoid (I read krebsonsecurity.com daily) and asked her to tell me what address I had on their file, knowing full well my home address can be found in a variety of ways,” Curt wrote in an email to this author. “She said, ‘One moment while I access that information.'”

After a short pause, a new voice came on the line.

“And here’s where I realized I was finally talking to a real human — a female with a slight French accent — who read me my correct address,” Curt recalled.

After another pause, Ms. Hansen’s voice came back on the line. While she was explaining that part of the package included free antivirus and anti-keylogging software, Curt asked her if he could opt-in to receive his credit reports while opting-out of installing the software.

“I’m sorry, can you repeat that?” the voice identifying itself as Ms. Hansen replied. Curt repeated himself. After another, “I’m sorry, can you repeat that,” Curt asked Ms. Hansen where she was from.

The voice confirmed what was indicated by the number displayed on his caller ID: That she was calling from Barrie, Ontario. Trying to throw the robot voice further off-script, Curt asked what the weather was like in Barrie, Ontario. Another Long pause. The voice continued describing the offered service.

“I asked again about the weather, and she said, ‘I’m sorry, I don’t have that information. Would you like me to transfer you to someone that does?’ I said yes and again the real person with a French accent started speaking, ignoring my question about the weather and saying that if I’d like to continue with the offer I needed to provide my date of birth. This is when I hung up and immediately called TD Bank.” No one from TD had called him, they assured him.

FULLY AUTOMATED PHONE PHISHING

And then there are the fully-automated voice phishing scams, which can be be equally convincing. Last week I heard from “Jon,” a cybersecurity professional with more than 30 years of experience under his belt (Jon asked to leave his last name out of this story).

Answering a call on his mobile device from a phone number in Missouri, Jon was greeted with the familiar four-note AT&T jingle, followed by a recorded voice saying AT&T was calling to prevent his phone service from being suspended for non-payment.

“It then prompted me to enter my security PIN to be connected to a billing department representative,” Jon said. “My number was originally an AT&T number (it reports as Cingular Wireless) but I have been on T-Mobile for several years, so clearly a scam if I had any doubt. However, I suspect that the average Joe would fall for it.”

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

Just as you would never give out personal information if asked to do so via email, never give out any information about yourself in response to an unsolicited phone call.

Phone phishing, like email scams, usually invokes an element of urgency in a bid to get people to let their guard down. If call has you worried that there might be something wrong and you wish to call them back, don’t call the number offered to you by the caller. If you want to reach your bank, call the number on the back of your card. If it’s another company you do business with, go to the company’s site and look up their main customer support number.

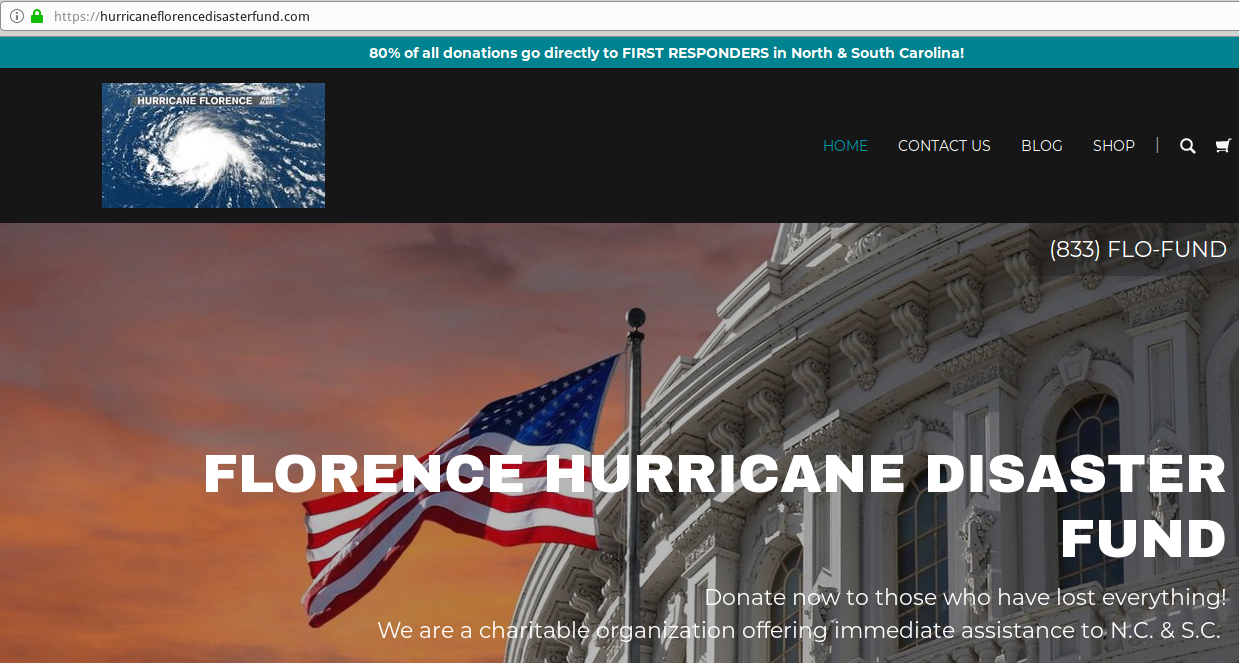

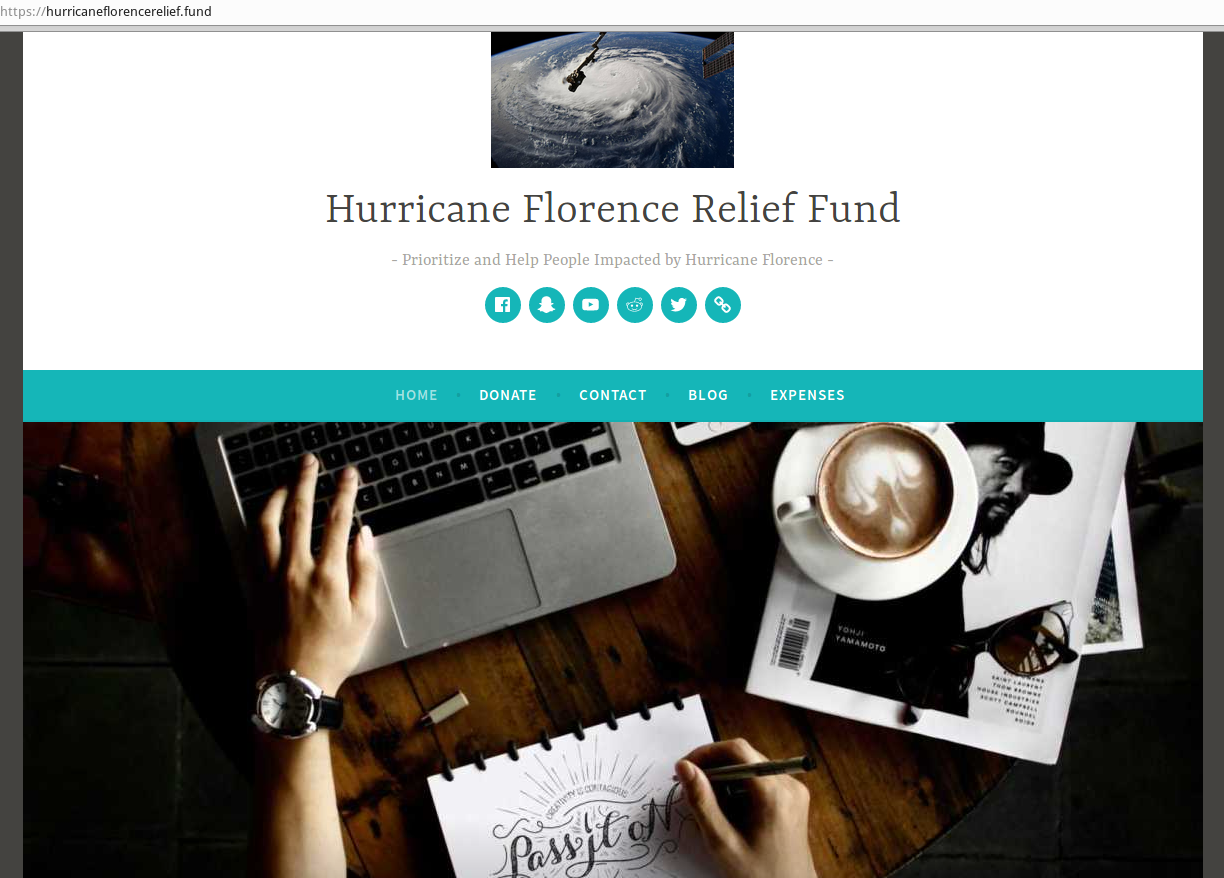

Unfortunately, this may take a little work. It’s not just banks and phone companies that are being impersonated by fraudsters. Reports on social media suggest many consumers also are receiving voice phishing scams that spoof customer support numbers at Apple, Amazon and other big-name tech companies. In many cases, the scammers are polluting top search engine results with phony 800-numbers for customer support lines that lead directly to fraudsters.

These days, scam calls happen on my mobile so often that I almost never answer my phone unless it appears to come from someone in my contacts list. The Federal Trade Commission’s do-not-call list does not appear to have done anything to block scam callers, and the major wireless carriers seem to be pretty useless in blocking incessant robocalls, even when the scammers are impersonating the carriers themselves, as in Jon’s case above.

I suspect people my age (mid-40s) and younger also generally let most unrecognized calls go to voicemail. It seems to be a very different reality for folks from an older generation, many of whom still primarily call friends and family using land lines, and who will always answer a ringing phone whenever it is humanly possible to do so.

It’s a good idea to advise your loved ones to ignore calls unless they appear to come from a friend or family member, and to just hang up the moment the caller starts asking for personal information.