Powerful New DDoS Method Adds Extortion

vendredi 2 mars 2018 à 23:41Attackers have seized on a relatively new method for executing distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks of unprecedented disruptive power, using it to launch record-breaking DDoS assaults over the past week. Now evidence suggests this novel attack method is fueling digital shakedowns in which victims are asked to pay a ransom to call off crippling cyberattacks.

On March 1, DDoS mitigation firm Akamai revealed that one of its clients was hit with a DDoS attack that clocked in at 1.3 Tbps, which would make it the largest publicly recorded DDoS attack ever.

The type of DDoS method used in this record-breaking attack abuses a legitimate and relatively common service called “memcached” (pronounced “mem-cash-dee”) to massively amp up the power of their DDoS attacks.

Installed by default on many Linux operating system versions, memcached is designed to cache data and ease the strain on heavier data stores, like disk or databases. It is typically found in cloud server environments and it is meant to be used on systems that are not directly exposed to the Internet.

Memcached communicates using the User Datagram Protocol or UDP, which allows communications without any authentication — pretty much anyone or anything can talk to it and request data from it.

Because memcached doesn’t support authentication, an attacker can “spoof” or fake the Internet address of the machine making that request so that the memcached servers responding to the request all respond to the spoofed address — the intended target of the DDoS attack.

Worse yet, memcached has a unique ability to take a small amount of attack traffic and amplify it into a much bigger threat. Most popular DDoS tactics that abuse UDP connections can amplify the attack traffic 10 or 20 times — allowing, for example a 1 mb file request to generate a response that includes between 10mb and 20mb of traffic.

But with memcached, an attacker can force the response to be thousands of times the size of the request. All of the responses get sent to the target specified in the spoofed request, and it requires only a small number of open memcached servers to create huge attacks using very few resources.

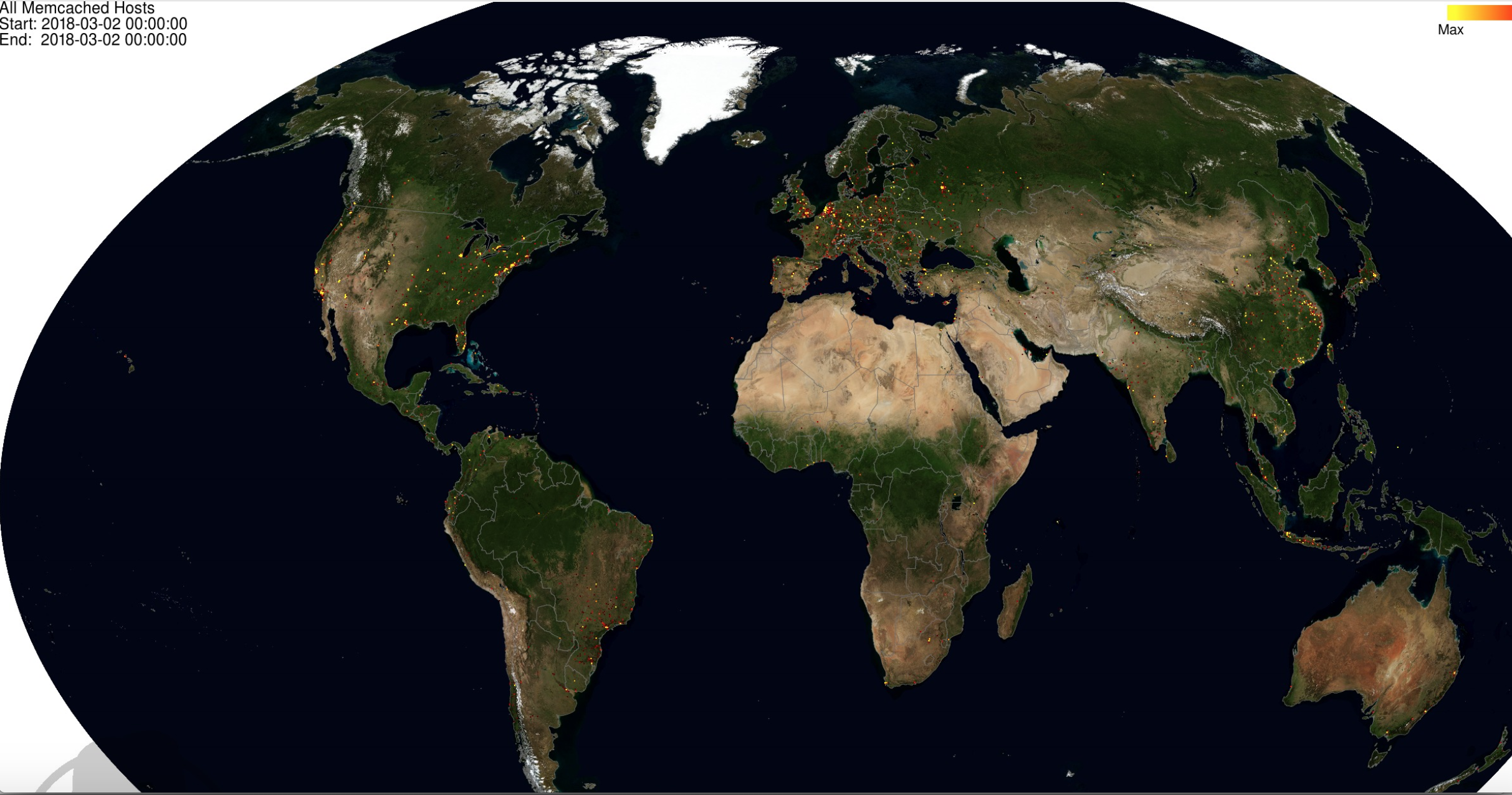

Akamai believes there are currently more than 50,000 known memcached systems exposed to the Internet that can be leveraged at a moment’s notice to aid in massive DDoS attacks.

Both Akamai and Qrator — a Russian DDoS mitigation company — published blog posts on Feb. 28 warning of the increased threat from memcached attacks.

“This attack was the largest attack seen to date by Akamai, more than twice the size of the September, 2016 attacks that announced the Mirai botnet and possibly the largest DDoS attack publicly disclosed,” Akamai said [link added]. “Because of memcached reflection capabilities, it is highly likely that this record attack will not be the biggest for long.”

According to Qrator, this specific possibility of enabling high-value DDoS attacks was disclosed in 2017 by a Chinese group of researchers from the cybersecurity 0Kee Team. The larger concept was first introduced in a 2014 Black Hat U.S. security conference talk titled “Memcached injections.”

DDOS VIA RANSOM DEMAND

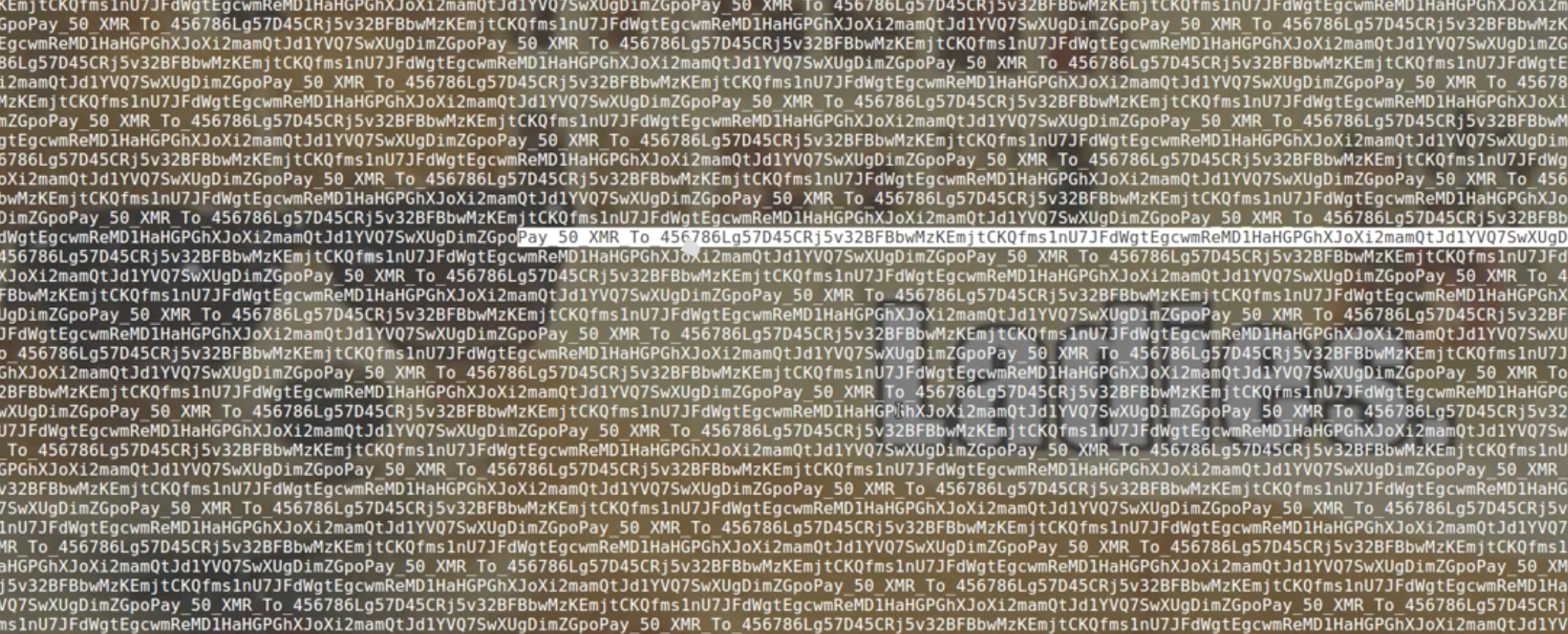

On Thursday, KrebsOnSecurity heard from several experts from Cybereason, a Boston-based security company that’s been closely tracking these memcached attacks. Cybereason said its analysis reveals the attackers are embedding a short ransom note and payment address into the junk traffic they’re sending to memcached services.

Cybereason said it has seen memcached attack payloads that consist of little more than a simple ransom note requesting payment of 50 XMR (Monero virtual currency) to be sent to a specific Monero account. In these attacks, Cybereason found, the payment request gets repeated until the file reaches approximately one megabyte in size.

Memcached can accept files and host files in temporary memory for download by others. So the attackers will place the 1 mb file full of ransom requests onto a server with memcached, and request that file thousands of times — all the while telling the service that the replies should all go to the same Internet address — the address of the attack’s target.

“The payload is the ransom demand itself, over and over again for about a megabyte of data,” said Matt Ploessel, principal security intelligence researcher at Cybereason. “We then request the memcached ransom payload over and over, and from multiple memcached servers to produce an extremely high volume DDoS with a simple script and any normal home office Internet connection. We’re observing people putting up those ransom payloads and DDoSsing people with them.”

Because it only takes a handful of memcached servers to launch a large DDoS, security researchers working to lessen these DDoS attacks have been focusing their efforts on getting Internet service providers (ISPs) and Web hosting providers to block traffic destined for the UDP port used by memcached (port 11211).

Ofer Gayer, senior product manager at security firm Imperva, said many hosting providers have decided to filter port 11211 traffic to help blunt these memcached attacks.

“The big packets here are very easy to mitigate because this is junk traffic and anything coming from that port (11211) can be easily mitigated,” Gayer said.

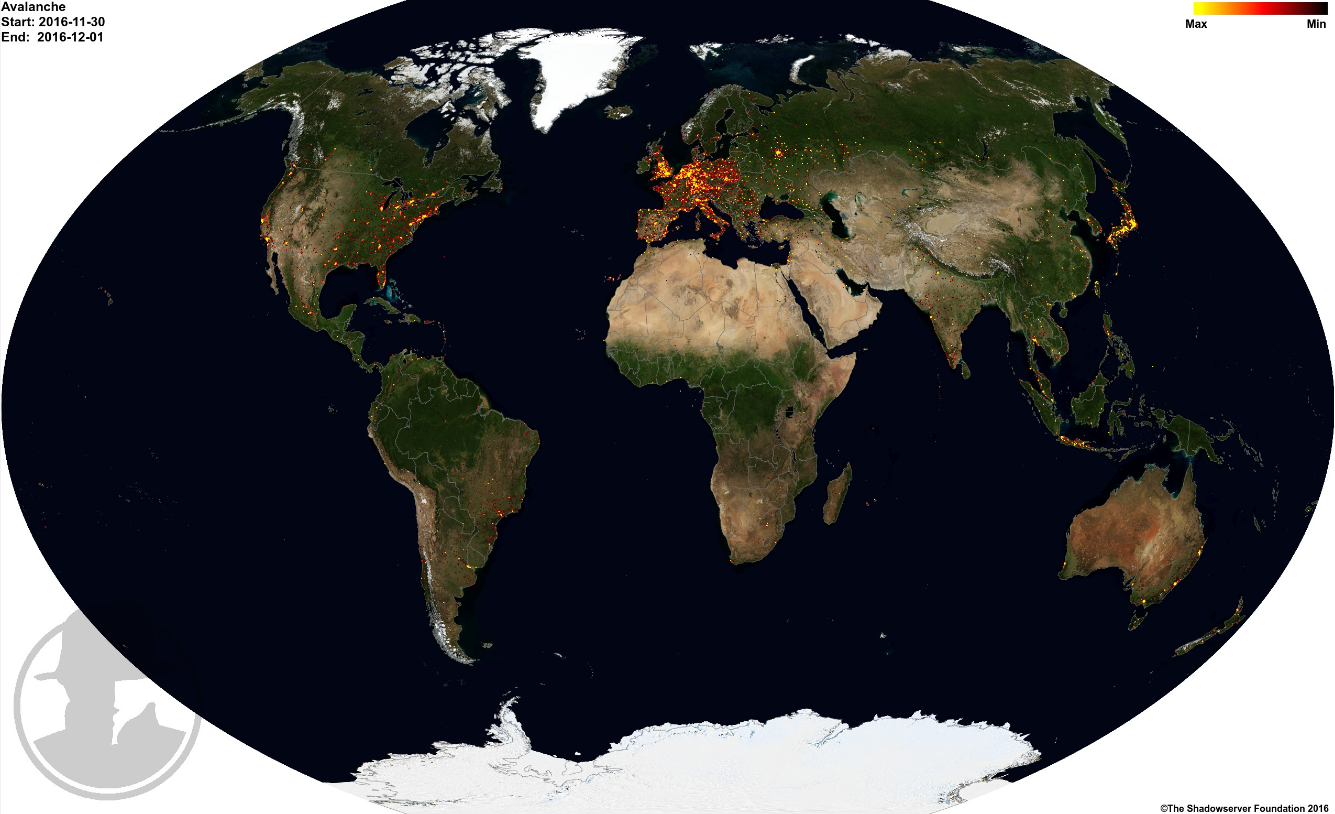

Several different organizations are mapping the geographical distribution of memcached servers that can be abused in these attacks. Here’s the world at-a-glance, from our friends at Shadowserver.org:

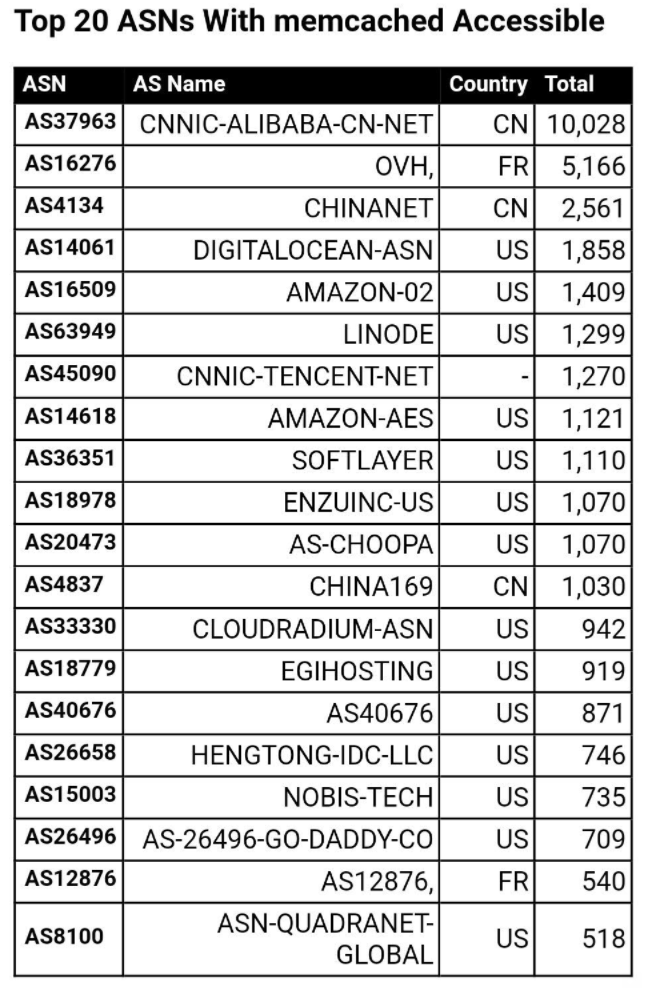

Here are the Top 20 networks that are hosting the most number of publicly accessible memcached servers at this moment, according to data collected by Cybereason:

The global ISPs with the most number of publicly available memcached servers.

DDoS monitoring site ddosmon.net publishes a live, running list of the latest targets getting pelted with traffic in these memcached attacks.

What do the stats at ddosmon.net tell us? According to netlab@360, memcached attacks were not super popular as an attack method until very recently.

“But things have greatly changed since February 24th, 2018,” netlab wrote in a Mar. 1 blog post, noting that in just a few days memcached-based DDoS went from less than 50 events per day, up to 300-400 per day. “Today’s number has already reached 1484, with an hour to go.”

Hopefully, the global ISP and hosting community can come together to block these memcached DDoS attacks. I am encouraged by what I have heard and seen so far, and hope that can continue in earnest before these attacks start becoming more widespread and destructive.

Here’s the Cybereason video from which that image above with the XMR ransom demand was taken: