How a Citadel Trojan Developer Got Busted

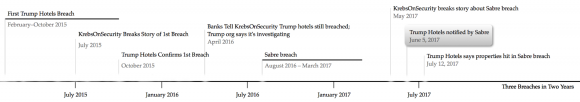

mardi 25 juillet 2017 à 18:11A U.S. District Court judge in Atlanta last week handed a five year prison sentence to Mark Vartanyan, a Russian hacker who helped develop and sell the once infamous and widespread Citadel banking trojan. This fact has been reported by countless media outlets, but far less well known is the fascinating backstory about how Vartanyan got caught.

For several years, Citadel ruled the malware scene for criminals engaged in stealing online banking passwords and emptying bank accounts. U.S. prosecutors say Citadel infected more than 11 million computers worldwide, causing financial losses of at least a half billion dollars.

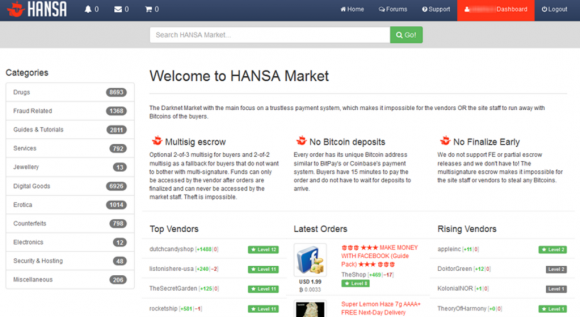

Like most complex banking trojans, Citadel was marketed and sold in secluded, underground cybercrime markets. Often the most time-consuming and costly aspect of malware sales and development is helping customers with any tech support problems they may have in using the crimeware.

In light of that, one innovation that Citadel brought to the table was to crowdsource some of this support work, easing the burden on the malware’s developers and freeing them up to spend more time improving their creations and adding new features.

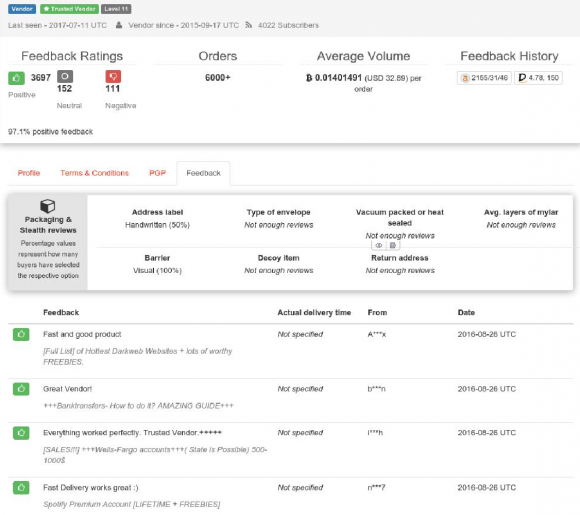

Citadel users discuss the merits of including a module to remove other parasites from host PCs.

Citadel boasted an online tech support system for customers designed to let them file bug reports, suggest and vote on new features in upcoming malware versions, and track trouble tickets that could be worked on by the malware developers and fellow Citadel users alike. Citadel customers also could use the system to chat and compare notes with fellow users of the malware.

It was this very interactive nature of Citadel’s support infrastructure that FBI agents would ultimately use to locate and identify Vartanyan, who went by the nickname “Kolypto.” The nickname of the core seller of Citadel was “Aquabox,” and the FBI was keen to identify Aquabox and any programmers he’d hired to help develop Citadel.

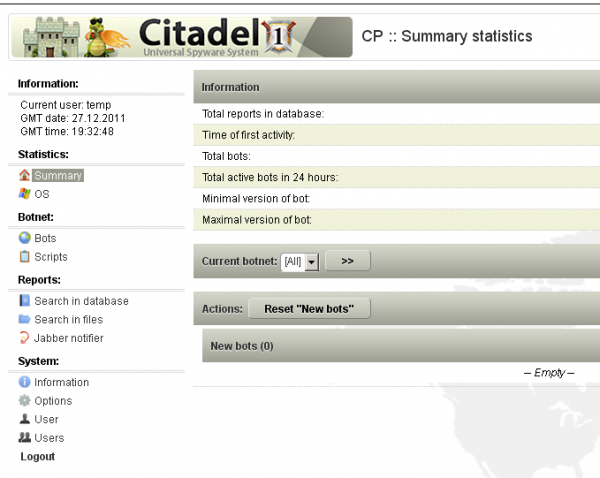

In June 2012, FBI agents bought several licenses of Citadel from Aquabox, and soon the agents were suggesting tweaks to the malware that they could use to their advantage. Posing as an active user of the malware, FBI agents informed the Citadel developers that that they’d discovered a security vulnerability in the Web-based interface that Citadel customers used to keep track of and collect passwords from infected systems (see screenshot below).

A screenshot of the Web-based Citadel botnet control panel.

Aquabox took the bait, and asked the FBI agents to upload a screen shot of the bug they’d found. As noted in this September 2015 story, the FBI agents uploaded the image to file-sharing giant Sendspace.com and then subpoenaed the logs from Sendspace to learn the Internet address of the user that later viewed and downloaded the file.

The IP address came back as the same one they had previously tied to Aquabox. The other address that accessed the file was in Ukraine and tied to Vartanyan. Prosecutors said Vartanyan’s address soon after was seen uploading to Sendspace a patched version of Citadel that supposedly fixed the vulnerability identified by the agents posing as Citadel users.

Mark Vartanyan. Source: Twitter.

“In the period August 2012 to January 2013, there were in total 48 files uploaded from Marks IP to Sendspace,” reads a story in the Norwegian daily VG that KrebsOnSecurity had translated into English here (PDF). “Those files were downloaded by ‘Aquabox’ with 2 IPs (193.105.134.50 and 149.154.155.81).”

Investigators would learn that Vartanyan was a Russian citizen who’d grown up in Ukraine. At the time of his arrest, Mark was living in Norway, which later extradited him to the United States for prosecution. In March 2017, Vartanyan pleaded guilty to one count of computer fraud, and was sentenced on July 19 to five years in federal prison.

Another Citadel developer, Dimitry Belorossov (a.k.a. “Rainerfox”), was arrested and sentenced in 2015 to four years and six months in prison after pleading guilty to distributing Citadel.

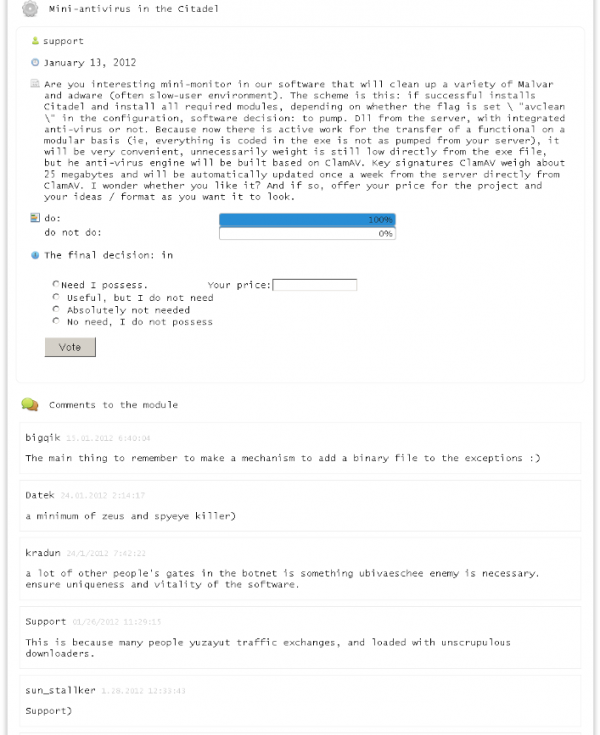

Early in its heydey, some text strings were added to the Citadel Trojan which named Yours Truly as the real author of Citadel (see screenshot below). While I obviously had no involvement in writing the trojan, I have written a great deal about its core victims — mainly dozens of small businesses here in the United States who saw their bank accounts drained of hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars after a Citadel infection.

A text string inside of the Citadel trojan. Source: AhnLab