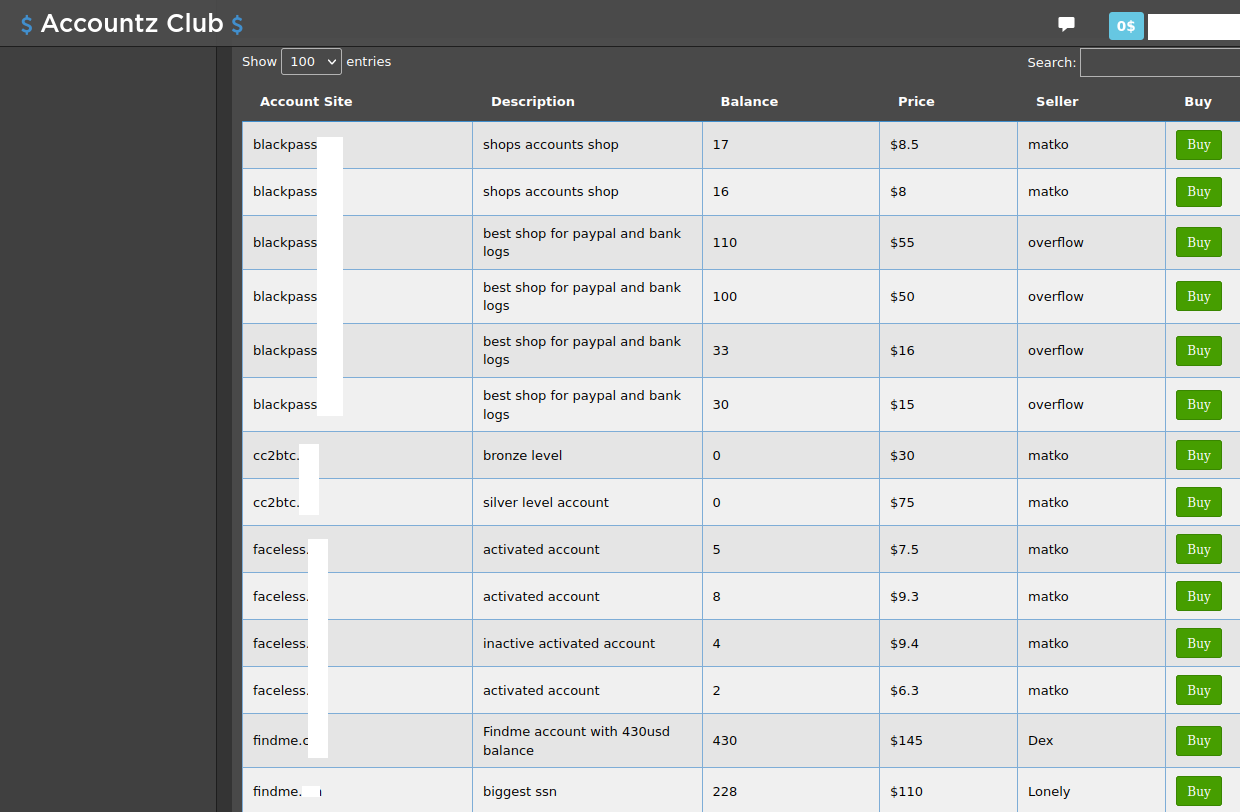

What’s worse than finding out that identity thieves took out a 546 percent interest payday loan in your name? How about a 900 percent interest loan? Or how about not learning of the fraudulent loan until it gets handed off to collection agents? One reader’s nightmare experience spotlights what can happen when ID thieves and hackers start targeting online payday lenders.

The reader who shared this story (and copious documentation to go with it) asked to have his real name omitted to avoid encouraging further attacks against his identity. So we’ll just call him “Jim.” Last May, someone applied for some type of loan in Jim’s name. The request was likely sent to an online portal that takes the borrower’s loan application details and shares them with multiple prospective lenders, because Jim said over the next few days he received dozens of emails and calls from lenders wanting to approve him for a loan.

Many of these lenders were eager to give Jim money because they were charging exorbitant 500-900 percent interest rates for their loans. But Jim has long had a security freeze on his credit file with the three major consumer credit reporting bureaus, and none of the lenders seemed willing to proceed without at least a peek at his credit history.

Among the companies that checked to see if Jim still wanted that loan he never applied for last May was Mountain Summit Financial (MSF), a lending institution owned by a Native American tribe in California called the Habematelol Pomo of Upper Lake.

Jim told MSF and others who called or emailed that identity thieves had applied for the funds using his name and information; that he would never take out a payday loan; and would they please remove his information from their database? Jim says MSF assured him it would, and the loan was never issued.

Jim spent months sorting out that mess with MSF and other potential lenders, but after a while the inquiries died down. Then on Nov. 27 — Thanksgiving Day weekend — Jim got a series of rapid-fire emails from MSF saying they’ve received his loan application, that they’d approved it, and that the funds requested were now available at the bank account specified in his MSF profile.

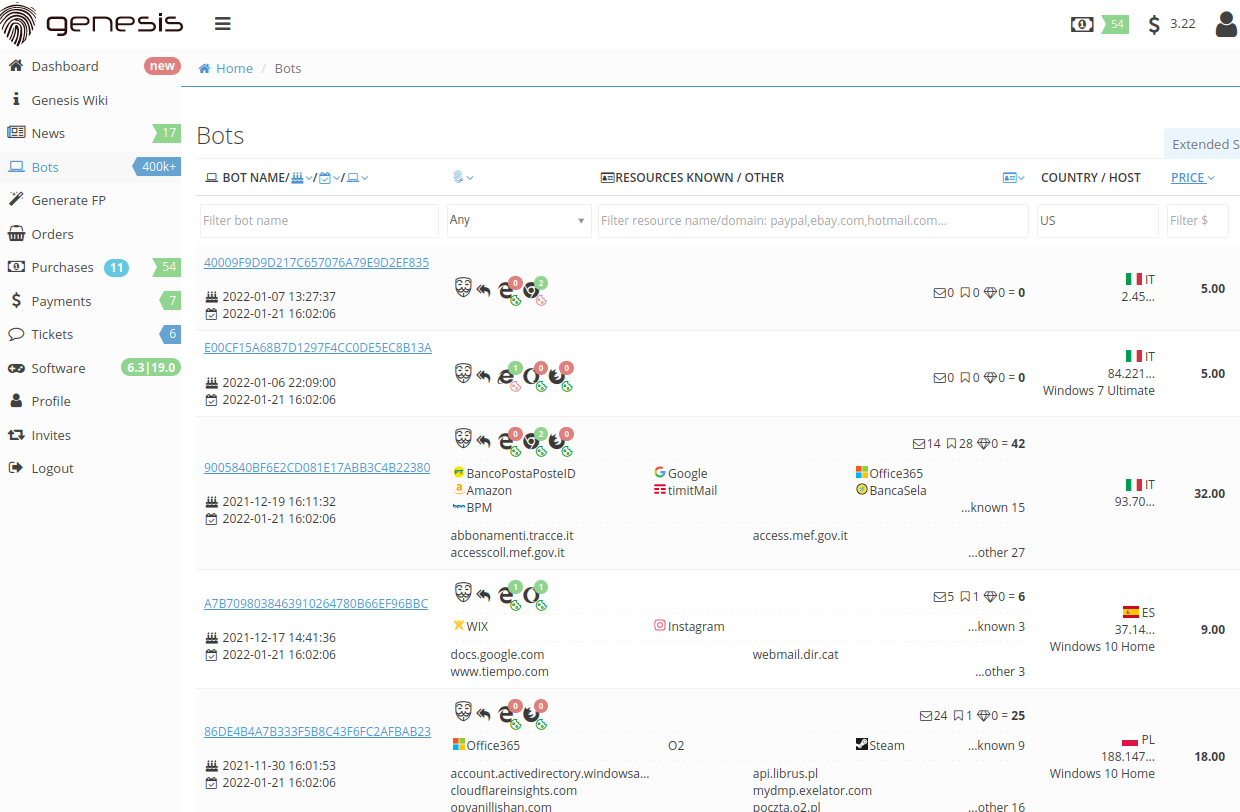

Curiously, the fraudsters had taken out a loan in Jim’s name with MSF using his real email address — the same email address the fraudsters had used to impersonate him to MSF back in May 2021. Although he didn’t technically have an account with MSF, their authentication system is based on email addresses, so Jim requested that a password reset link be sent to his email address. That worked, and once inside the account Jim could see more about the loan details:

The terms of the unauthorized loan in Jim’s name from MSF.

Take a look at that 546.56 percent interest rate and finance charges listed in this $1,000 loan. If you pay this loan off in a year at the suggested bi-weekly payment amounts, you will have paid $3,903.57 for that $1,000.

Jim contacted MSF as soon as they opened the following week and found out the money had already been dispersed to a Bank of America account Jim didn’t recognize. MSF had Jim fill out an affidavit claiming the loan was the result of identity theft, which necessitated filing a report with the local police and a number of other steps. Jim said numerous calls to Bank of America’s fraud team went nowhere because they refused to discuss an account that was not in his name.

Jim said MSF ultimately agreed that the loan wasn’t legitimate, but they couldn’t or wouldn’t tell him how his information got pushed through to a loan — even though MSF was never able to pull his credit file.

Then in mid-January, Jim heard from MSF via snail mail that they’d discovered a data breach.

“We believe the outsider may have had an opportunity to access the accounts of certain customers, including your account, at which point they would be able to view personal information pertaining to that customer and potentially obtain an unauthorized loan using the customer’s credentials,” MSF said.

MSF said the personal information involved in this incident may have included name, date of birth, government-issued identification numbers (e.g., SSN or DLN), bank account number and routing number, home address, email address, phone number and other general loan information.

A portion of the Jan. 14, 2022 breach notification letter from tribal lender Mountain Summit Financial.

Nevermind that his information was only in MSF’s system because of an earlier attempt by ID thieves: The intruders were able to update his existing (never-deleted) record with new banking information and then push the application through MSF’s systems.

“MSF was the target of a suspected third-party attack,” the company said, noting that it was working with the FBI, the California Sheriff’s Office, and the Tribal Commission for Lake County, Calif. “Ultimately, MSF confirmed that these trends were part of an attack that originated outside of the company.”

MSF has not responded to questions about the aforementioned third party or parties that may be involved. But it is possible that other tribal lenders could have been affected: Jim said that not long after the phony MSF payday loan was pushed through, he received at least three inquiries in rapid succession from other lenders who were all of a sudden interested in offering him a loan.

In a statement sent to KrebsOnSecurity, MSF said it was “the victim of a malicious attack that originated outside of the company, by unknown perpetrators.”

“As soon as the issue was uncovered, the company initiated cybersecurity incident response measures to protect and secure its information; and notified law enforcement and regulators,” MSF wrote. “Additionally, the company has notified individuals whose personal identifiable information may have been impacted by this crime and is actively working with law enforcement in its investigation. As this is an ongoing criminal investigation, we can make no additional comment at this time.”

According to the Native American Financial Services Association (NAFSA), a trade group in Washington, D.C. representing tribal lenders, the short-term installment loan products offered by NAFSA members are not payday loans but rather “installment loans” — which are amortized, have a definite loan term, and require payments that go toward not just interest, but that also pay down the loan principal.

NAFSA did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Nearly all U.S. states have usury laws that limit the amount of interest a company can charge on a loan, but those limits traditionally haven’t applied to tribal lenders.

Leslie Bailey is a staff attorney at Public Justice, a nonprofit legal advocacy organization in Oakland, Calif. Bailey says an increasing number of online payday lenders have sought affiliations with Native American tribes in an effort to take advantage of the tribes’ special legal status as sovereign nations.

“The reason is clear: Genuine tribal businesses are entitled to ‘tribal immunity,’ meaning they can’t be sued,” Bailey wrote in a blog post. “If a payday lender can shield itself with tribal immunity, it can keep making loans with illegally-high interest rates without being held accountable for breaking state usury laws.”

Bailey said in one common type of arrangement, the lender provides the necessary capital, expertise, staff, technology, and corporate structure to run the lending business and keeps most of the profits. In exchange for a small percent of the revenue (usually 1-2%), the tribe agrees to help draw up paperwork designating the tribe as the owner and operator of the lending business.

“Then, if the lender is sued in court by a state agency or a group of cheated borrowers, the lender relies on this paperwork to claim it is entitled to immunity as if it were itself a tribe,” Bailey wrote. “This type of arrangement — sometimes called ‘rent-a-tribe’ — worked well for lenders for a while, because many courts took the corporate documents at face value rather than peering behind the curtain at who’s really getting the money and how the business is actually run. But if recent events are any indication, legal landscape is shifting towards increased accountability and transparency.”

In 2017, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau sued four tribal online payday lenders in federal court — including Mountain Summit Financial — for allegedly deceiving consumers and collecting debt that was not legally owed in many states. All four companies are owned by the Habematolel Pomo of Upper Lake.

The CFPB later dropped that inquiry. But a class action lawsuit (PDF) against those same four lenders is proceeding in Virginia, where a group of plaintiffs have alleged the defendants violated the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) and Virginia usury laws by charging interest rates between 544 and 920 percent.

According to Buckley LLP, a financial services law firm based in Washington, D.C., a district court dismissed the RICO claims but denied the defense’s motion to compel arbitration and dismiss the case, ruling that the arbitration provision was unenforceable as a prospective waiver of the borrowers’ federal rights and that the defendants could not claim tribal sovereign immunity. The district court also “held the loan agreements’ choice of tribal law unenforceable as a violation of Virginia’s strong public policy against unregulated lending of usurious loans.”

Buckley notes that on Nov. 16, 2021, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit upheld the district court ruling, concluding that the arbitration clauses in the loan agreements “impermissibly force borrowers to waive their federal substantive rights under federal consumer protection laws, and contained an unenforceable tribal choice-of-law provision because Virginia law caps general interest rates at 12 percent.”

Jim said he learned of the Thanksgiving weekend MSF loan only because the hackers apparently figured it was easier to push through loans using existing MSF customer account information than it was to alter anything in the records other than the bank account for receiving the funds.

But had the hackers changed the email address, Jim might have first found out about the loan when the collection agencies came calling. And by then, his exorbitant loan would be in default and racking up some wicked late charges.

Jim says he’s still hopping mad at MSF, and these days he’s just waiting for the other shoe to drop.

“They issued this loan in my name without verification and without even checking my credit at all, even though they were already on notice that they shouldn’t have been dealing with me from the May incident,” Jim said. “I still feel like I’m going to get that call at some point from a collection agency asking why I haven’t been making payments on some installment loan I never asked for.”