Who Is Marcus Hutchins?

mardi 5 septembre 2017 à 12:50In early August 2017, FBI agents in Las Vegas arrested 23-year-old British security researcher Marcus Hutchins on suspicion of authoring and/or selling “Kronos,” a strain of malware designed to steal online banking credentials. Hutchins was virtually unknown to most in the security community until May 2017 when the U.K. media revealed him as the “accidental hero” who inadvertently halted the global spread of WannaCry, a ransomware contagion that had taken the world by storm just days before.

Relatively few knew it before his arrest, but Hutchins has for many years authored the popular cybersecurity blog MalwareTech. When this fact became more widely known — combined with his hero status for halting Wannacry — a great many MalwareTech readers quickly leapt to his defense to denounce his arrest. They reasoned that the government’s case was built on flimsy and scant evidence, noting that Hutchins has worked tirelessly to expose cybercriminals and their malicious tools. To date, some 226 supporters have donated more than $14,000 to his defense fund.

Marcus Hutchins, just after he was revealed as the security expert who stopped the WannaCry worm. Image: twitter.com/malwaretechblog

At first, I did not believe the charges against Hutchins would hold up under scrutiny. But as I began to dig deeper into the history tied to dozens of hacker forum pseudonyms, email addresses and domains he apparently used over the past decade, a very different picture began to emerge.

In this post, I will attempt to describe and illustrate more than three weeks’ worth of connecting the dots from what appear to be Hutchins’ earliest hacker forum accounts to his real-life identity. The clues suggest that Hutchins began developing and selling malware in his mid-teens — only to later develop a change of heart and earnestly endeavor to leave that part of his life squarely in the rearview mirror.

GH0STHOSTING/IARKEY

I began this investigation with a simple search of domain name registration records at domaintools.com [full disclosure: Domain Tools recently was an advertiser on this site]. A search for “Marcus Hutchins” turned up a half dozen domains registered to a U.K. resident by the same name who supplied the email address “surfallday2day@hotmail.co.uk.”

One of those domains — Gh0sthosting[dot]com (the third character in that domain is a zero) — corresponds to a hosting service that was advertised and sold circa 2009-2010 on Hackforums[dot]net, a massively popular forum overrun with young, impressionable men who desperately wish to be elite coders or hackers (or at least recognized as such by their peers).

The surfallday2day@hotmail.co.uk address tied to Gh0sthosting’s initial domain registration records also was used to register a Skype account named Iarkey that listed its alias as “Marcus.” A Twitter account registered in 2009 under the nickname “Iarkey” points to Gh0sthosting[dot]com.

Gh0sthosting was sold by a Hackforums user who used the same Iarkey nickname, and in 2009 Iarkey told fellow Hackforums users in a sales thread for his business that Gh0sthosting was “mainly for blackhats wanting to phish.” In a separate post just a few days apart from that sales thread, Iarkey responds that he is “only 15” years old, and in another he confirms that his email address is surfallday2day@hotmail.co.uk.

A review of the historic reputation tied to the Gh0sthosting domain suggests that at least some customers took Iarkey up on his offer: Malwaredomainlist.com, for example, shows that around this same time in 2009 Gh0sthosting was observed hosting plenty of malware, including trojan horse programs, phishing pages and malware exploits.

A “reverse WHOIS” search at Domaintools.com shows that Iarkey’s surfallday2day email address was used initially to register several other domains, including uploadwith[dot]us and thecodebases[dot]com.

Shortly after registering Gh0sthosting and other domains tied to his surfallday2day@hotmail.co.uk address, Iarkey evidently thought better of including his real name and email address in his domain name registration records. Thecodebases[dot]com, for example, changed its WHOIS ownership to a “James Green” in the U.K., and switched the email to “herpderpderp2@hotmail.co.uk.”

A reverse WHOIS lookup at domaintools.com for that email address shows it was used to register a Hackforums parody (or phishing?) site called Heckforums[dot]net. The domain records showed this address was tied to a Hackforums clique called “Atthackers.” The records also listed a Michael Chanata from Florida as the owner. We’ll come back to Michael Chanata and Atthackers at the end of this post.

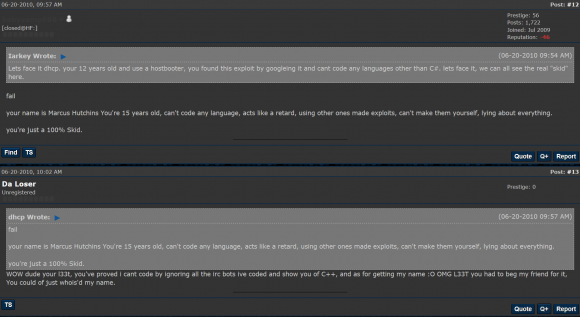

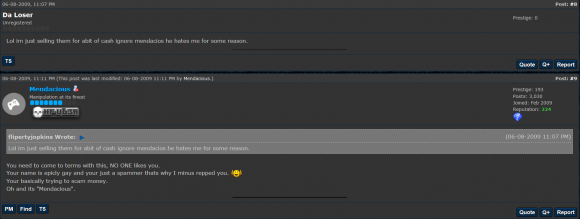

DA LOSER/FLIPERTYJOPKINS

As early as 2009, Iarkey was outed several times on Hackforums as being Marcus Hutchins from the United Kingdom. In most of those instances he makes no effort to deny the association — and in a handful of posts he laments that fellow members felt the need to “dox” him by posting his real address and name in the hacking forum for all to see.

Iarkey, like many other extremely active Hackforums users, changed his nickname on the forum constantly, and two of his early nicknames on Hackforums around 2009 were “Flipertyjopkins” and “Da Loser“.

Happily, Hackforums has a useful feature that allows anyone willing to take the time to dig through a user’s postings to learn when and if that user was previously tied to another account.

This is especially evident in multi-page Hackforums discussion threads that span many days or weeks: If a user changes his nickname during that time, the forum is set up so that it includes the user’s most previous nickname in any replies that quote the original nickname — ostensibly so that users can follow along with who’s who and who said what to whom.

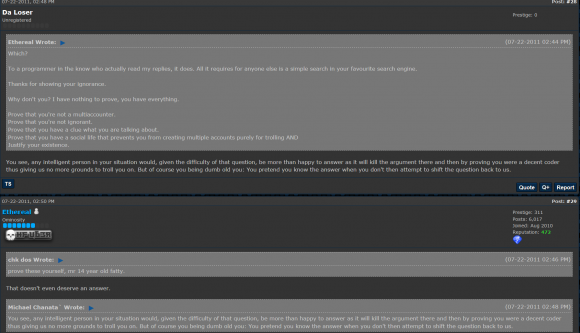

In the screen shot below, for instance, we can see one of Hutchins’ earliest accounts — Da Loser — being quoted under his Flipertyjopkins nickname.

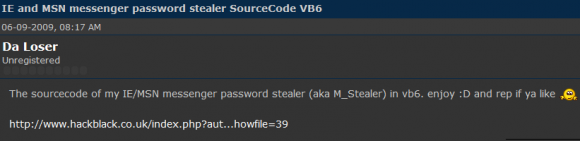

Both the Da Loser and Flipertyjopkins identities on Hackforums referenced the same domains in 2009 as theirs — Gh0sthosting — as well as another domain called “hackblack.co[dot]uk.” Da Loser references the hackblack domain as the place where other Hackforums users can download “the sourcecode of my IE/MSN messenger password stealer (aka M_Stealer).”

In another post, Da Loser brags about how his password stealing program goes undetected by multiple antivirus scanners, pointing to a (now deleted) screenshot at a Photobucket account for a “flipertyjopkins”:

Another screenshot from Da Loser’s postings in June 2009 shows him advertising the Hackblack domain and the Surfallday2day@hotmail.co.uk address:

Hackforums user “Da Loser” advertises his “Hackblack” hosting and points to the surfallday2day email address.

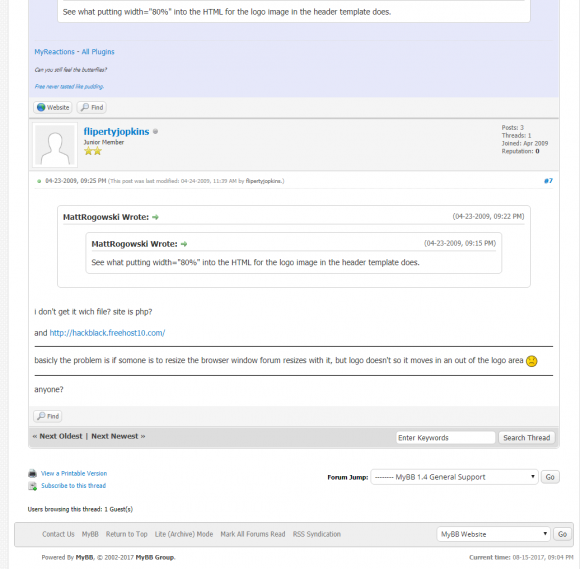

An Internet search for this Hackblack domain reveals a thread on the Web hosting forum MyBB started by a user Flipertyjopkins, who asks other members for help configuring his site, which he lists as http://hackblack.freehost10[dot]com.

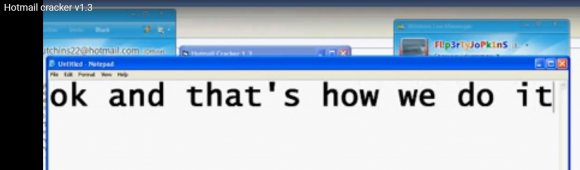

Poking around the Web for these nicknames and domains turned up a Youtube user account named Flipertyjopkins that includes several videos uploaded 7-8 years ago that instruct viewers on how to use various types of password-stealing malware. In one of the videos — titled “Hotmail cracker v1.3” — Flipertyjopkins narrates how to use a piece of malware by the same name to steal passwords from unsuspecting victims.

Approximately two minutes and 48 seconds into the video, we can briefly see an MSN Messenger chat window shown behind the Microsoft Notepad application he is using to narrate the video. The video clearly shows that the MSN Messenger client is logged in to with the address “hutchins22@hotmail.com.”

To close out the discussion of Flipertyjopkins, I should note that this email address showed up multiple times in the database leak from Hostinger.co.uk, a British Web hosting company that got hacked in 2015. A copy of that database can be found in several places online, and it shows that one Hostinger customer named Marcus used an account under the email address flipertyjopkins@gmail.com.

According to the leaked user database, the password for that account — “emmy009” — also was used to register two other accounts at Hostinger, including the usernames “hacker” (email address: flipertyjopkins@googlemail.com) and “flipertyjopkins” (email: surfallday2day@hotmail.co.uk).

ELEMENT PRODUCTS/GONE WITH THE WIND

Most of the activities and actions that can be attributed to Iarkey/Flipertyjopkins/Da Loser et. al on Hackforums are fairly small-time — and hardly rise to the level of coding from scratch a complex banking trojan and selling it to cybercriminals.

However, multiple threads on Hackforums state that Hutchins around 2011-2012 switched to two new nicknames that corresponded to users who were far more heavily involved in coding and selling complex malicious software: “Element Products,” and later, “Gone With The Wind.”

Hackforums’ nickname preservation feature leaves little doubt that the user Element Products at some point in 2012 changed his nickname to Gone With the Wind. However, for almost a week I could not see any signs of a connection between these two accounts and the ones previously and obviously associated with Hutchins (Flipertyjopkins, Iarkey, etc.).

In the meantime, I endeavored to find out as much as possible about Element Products — a suite of software and services including a keystroke logger, a “stresser” or online attack service, as well as a “no-distribute” malware scanner.

Unlike legitimate scanning services such as Virustotal — which scan malicious software against dozens of antivirus tools and then share the output with all participating antivirus companies — no-distribute scanners are made and marketed to malware authors who wish to see how broadly their malware is detected without tipping off the antivirus firms to a new, more stealthy version of the code.

Indeed, Element Scanner — which was sold in subscription packages starting at $40 per month — scanned all customer malware with some 37 different antivirus tools. But according to posts from Gone With the Wind, the scanner merely resold the services of scan4you[dot]net, a multiscanner that was extremely powerful and popular for several years across a variety of underground cybercrime forums.

According to a story at Bleepingcomputer.com, scan4you disappeared in July 2017, around the same time that two Latvian men were arrested for running an unnamed no-distribute scanner.

[Side note: Element Scanner was later incorporated as the default scanning application of “Blackshades,” a remote access trojan that was extremely popular on Hackforums for several years until its developers and dozens of customers were arrested in an international law enforcement sting in May 2014. Incidentally, as the story linked in the previous sentence explains, the administrator and owner of Hackforums would play an integral role in setting up many of his forum’s users for the Blackshades sting operation.]

According to one thread on Hackforums, Element Products was sold in 2012 to another Hackforums user named “Dal33t.” This was the nickname used by Ammar Zuberi, a young man from Dubai who — according to this this January 2017 KrebsOnSecurity story — may have been associated with a group of miscreants on Hackforums that specialized in using botnets to take high-profile Web sites offline. Zuberi could not be immediately reached for comment.

I soon discovered that Element Products was by far the least harmful product that this user sold on Hackforums. In a separate thread in 2012, Element Products announces the availability of a new product he had for sale — dubbed the “Ares Form Grabber” — a program that could be used to surreptitiously steal usernames and passwords from victims.

Element Products/Gone With The Wind also advertised himself on Hackforums as an authorized reseller of the infamous exploit kit known as “Blackhole.” Exploit kits are programs made to be stitched into hacked and malicious Web sites so that when visitors browse to the site with outdated and insecure browser plugins the browser is automatically infected with whatever malware the attacker wishes to foist on the victim.

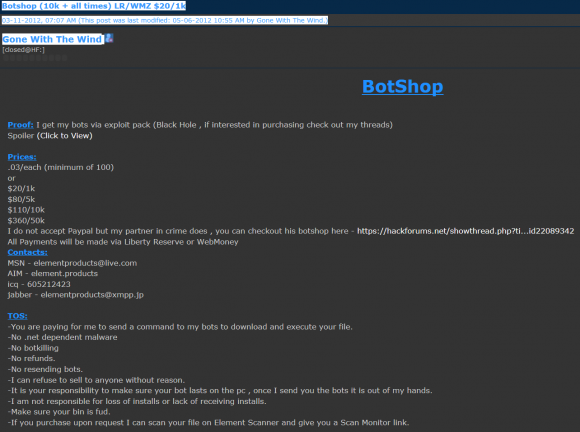

In addition, Element Products ran a “bot shop,” in which he sold access to bots claimed to have enslaved through his own personal use of Blackhole:

Gone With The Wind’s “Bot Shop,” which sold access to computers hacked with the help of the Blackhole exploit kit.

A bit more digging showed that the Element Products user on Hackforums co-sold his wares along with another Hackforums user named “Kill4Joy,” who advertised his contact address as kill4joy@live.com.

Ironically, Hackforums was itself hacked in 2012, and a leaked copy of the user database from that hack shows this Kill4Joy user initially registered on the forum in 2011 with the email address rohang93@live.com.

A reverse WHOIS search at domaintools.com shows that email address was used to register several domain names, including contegoprint.info. The registration records for that domain show that it was registered by a Rohan Gupta from Illinois.

I learned that Gupta is now attending graduate school at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he is studying computer engineering. Reached via telephone, Gupta confirmed that he worked with the Hackforums user Element Products six years ago, but said he only handled sales for the Element Scanner product, which he says was completely legal.

“I was associated with Element Scanner which was non-malicious,” Gupta said. “It wasn’t black hat, and I wasn’t associated with the programming, I just assisted with the sales.”

Gupta said his partner and developer of the software went by the name Michael Chanata and communicated with him via a Skype account registered to the email address atthackers@hotmail.com.

Recall that we heard at the beginning of this story that the name Michael Chanata was tied to Heckforums.net, a domain closely connected to the Iarkey nickname on Hackforums. Curious to see if this Michael Chanata character showed up somewhere on Hackforums, I used the forum’s search function to find out.

The following screenshot from a July 2011 Hackforums thread suggests that Michael Chanata was yet another nickname used by Da Loser, a Hackforums account associated with Marcus Hutchins’ early email addresses and Web sites.

BV1/ORGY

Interesting connections, to be sure, but I wasn’t satisfied with this finding and wanted more conclusive evidence of the supposed link. So I turned to “passive DNS” tools from Farsight Security — which keeps a historic record of which domain names map to which IP addresses.

Using Farsight’s tools, I found that Element Scanner’s various Web sites (elementscanner[dot]com/net/su/ru) were at one point hosted at the Internet address 184.168.88.189 alongside just a handful of other interesting domains, including bigkeshhosting[dot]com and bvnetworks[dot]com.

At first, I didn’t fully recognize the nicknames buried in each of these domains, but a few minutes of searching on Hackforums reminded me that bigkeshhosting[dot]com was a project run by a Hackforums user named “Orgy.”

I originally wrote about Orgy — whose real name is Robert George Danielson — in a 2012 story about a pair of stresser or “booter” (DDoS-for-hire) sites. As noted in that piece, Danielson has had several brushes with the law, including a guilty plea for stealing multiple firearms from the home of a local police chief.

I also learned that the bvnetworks[dot]com domain belonged to Orgy’s good friend and associate on Hackforums — a user who for many years went by the nickname “BV1.” In real life, BV1 is 27-year-old Brendan Johnston, a California man who went to prison in 2014 for his role in selling the Blackshades trojan.

When I discovered the connection to BV1, I searched my inbox for anything related to this nickname. Lo and behold, I found an anonymous tip I’d received through KrebsOnSecurity.com’s contact form in March 2013 which informed me of BV1’s real identity and said he was close friends with Orgy and the Hackforums user Iarkey.

According to this anonymous informant, Iarkey was an administrator of an Internet relay chat (IRC) forum that BV1 and Orgy frequented called irc.voidptr.cz.

“You already know that Orgy is running a new booter, but BV1 claims to have ‘left’ the hacking business because all the information on his family/himself has been leaked on the internet, but that is a lie,” the anonymous tipster wrote. “If you connect to http://irc.voidptr. cz ran by ‘touchme’ aka ‘iarkey’ from hackforums you can usually find both BV1 and Orgy in there.”

TOUCHME/TOUCH MY MALWARE/MAYBE TOUCHME

Until recently, I was unfamiliar with the nickname TouchMe. Naturally, I started digging into Hackforums again. An exhaustive search on the forum shows that TouchMe — and later “Touch Me Maybe” and “Touch My Malware” — were yet other nicknames for the same account.

In a Hackforums post from July 2012, the user Touch Me Maybe pointed to a writeup that he claimed to have authored on his own Web site: touchmymalware.blogspot.com:

The Hackforums user “Touch Me Maybe” seems to refer to his own blog and malware analysis at touchmymalware.blogspot.com, which now redirects to Marcus Hutchins’ blog — Malwaretech.com

If you visit this domain name now, it redirects to Malwaretech.com, which is the same blog that Hutchins was updating for years until his arrest in August.

There are other facts to support a connection between MalwareTech and the IRC forum voidptr.cz: A passive DNS scan for irc.voidptr.cz at Farsight Security shows that at one time the IRC channel was hosted at the Internet address 52.86.95.180 — where it shared space with just one other domain: irc.malwaretech.com.

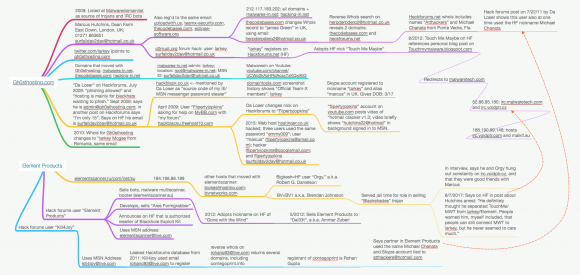

All of the connections explained in this blog post — and some that weren’t — can be seen in the following mind map that I created with the excellent MindNode Pro for Mac.

A mind map I created to keep track of the myriad data points mentioned in this story. Click the image to enlarge.

Following Hutchins’ arrest, multiple Hackforums members posted what they suspected about his various presences on the forum. In one post from October 2011, Hackforums founder and administrator Jesse “Omniscient” LaBrocca said Iarkey had hundreds of accounts on Hackforums.

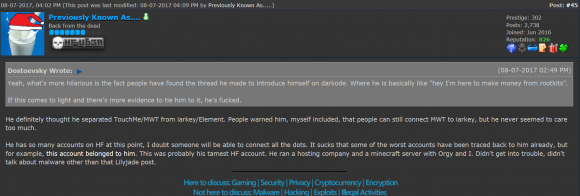

In one of the longest threads on Hackforums about Hutchins’ arrest there are several postings from a user named “Previously Known As” who self-identifies in that post and multiple related threads as BV1. In one such post, dated Aug. 7, 2017, BV1 observes that Hutchins failed to successfully separate his online selves from his real life identity.

Brendan “BV1” Johnston says he worried his old friend’s operational security mistakes would one day catch up with him.

“He definitely thought he separated TouchMe/MWT from iarkey/Element,” said BV1. “People warned him, myself included, that people can still connect MWT to iarkey, but he never seemed to care too much. He has so many accounts on HF at this point, I doubt someone will be able to connect all the dots. It sucks that some of the worst accounts have been traced back to him already. He ran a hosting company and a Minecraft server with Orgy and I.”

In a brief interview with KrebsOnSecurity, Brendan “BV1” Johnston said Hutchins was a good friend. Johnston said Hutchins had — like many others who later segued into jobs in the information security industry — initially dabbled in the dark side. But Johnston said his old friend sincerely tried to turn things around in late 2012 — when Gone With the Wind sold most of his coding projects to other Hackforums members and began focusing on blogging about poorly-written malware.

“I feel like I know Marcus better than most people do online, and when I heard about the accusations I was completely shocked,” Johnston said. “He tried for such a long time to steer me down a straight and narrow path that seeing this tied to him didn’t make sense to me at all.”

Let me be clear: I have no information to support the claim that Hutchins authored or sold the Kronos banking trojan. According to the government, Hutchins did so in 2014 on the Dark Web marketplace AlphaBay — which was taken down in July 2017 as part of a coordinated, global law enforcement raid on AlphaBay sellers and buyers alike.

However, the findings in this report suggest that for several years Hutchins enjoyed a fairly successful stint coding malicious software for others, said Nicholas Weaver, a security researcher at the International Computer Science Institute and a lecturer at UC Berkeley.

“It appears like Mr. Hutchins had a significant and prosperous blackhat career that he at least mostly gave up in 2013,” Weaver said. “Which might have been forgotten if it wasn’t for the involuntary British press coverage on WannaCry raising his profile and making him out as a ‘hero’.”

Weaver continued:

“I can easily imagine the Feds taking the opportunity to use a penny-ante charge against a known ‘bad guy’ when they can’t charge for more significant crimes,” he said. “But the Feds would have done far less collateral damage if they actually provided a criminal complaint with these sorts of detail rather than a perfunctory indictment.”

Hutchins did not try to hide the fact that he has written and published unique malware strains, which in the United States at least is a form of protected speech.

In December 2014, for example, Hutchins posted to his Github page the source code to TinyXPB, malware he claims to have written that is designed to seize control of a computer so that the malware loads before the operating system can even boot up.

While the publicly available documents related to his case are light on details, it seems clear that prosecutors can make a case against those who attempt to sell malware to cybercriminals — such as on hacker forums like AlphaBay — if they can demonstrate the accused had knowledge and intent that the malware would be used to commit a crime.

The Justice Department’s indictment against Hutchins suggests that the prosecution is relying heavily on the word of an unnamed co-conspirator who became a confidential informant for the government. Update, 9:08 a.m.: Several readers on Twitter disagreed with the previous statement, noting that U.S. prosecutors have said the other unnamed suspect in the Hutchins indictment is still at large.

Original story:

According to a story at BankInfoSecurity, the evidence submitted by prosecutors for the government includes:

- Statements made by Hutchins after he was arrested.

- A CD containing two audio recordings from a county jail in Nevada where he was detained by the FBI.

- 150 pages of Jabber chats between the defendant and an individual.

- Business records from Apple, Google and Yahoo.

- Statements (350 pages) by the defendant from another internet forum, which were seized by the government in another district.

- Three to four samples of malware.

- A search warrant executed on a third party, which may contain some privileged information.

Hutchins declined to comment for this story, citing his ongoing prosecution. He has pleaded not guilty to all four counts against him, including conspiracy to distribute malicious software with the intent to cause damage to 10 or more affected computers without authorization, and conspiracy to distribute malware designed to intercept protected electronic communications. FBI officials have not yet responded to requests for comment.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued an alert Monday urging consumers to be on the lookout for a potential surge in charity scams. The FTC advises those who wish to donate to stick to charities they know, and to be on the lookout for charities or relief Web sites that seem to have sprung up overnight in response to current events (such as houstonfloodrelief.net, registered on Aug. 28, 2017). Sometimes these sites are set up by well-meaning people with the best of intentions (however misguided), but it’s best not to take a chance.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued an alert Monday urging consumers to be on the lookout for a potential surge in charity scams. The FTC advises those who wish to donate to stick to charities they know, and to be on the lookout for charities or relief Web sites that seem to have sprung up overnight in response to current events (such as houstonfloodrelief.net, registered on Aug. 28, 2017). Sometimes these sites are set up by well-meaning people with the best of intentions (however misguided), but it’s best not to take a chance.