In 2015, police departments worldwide started finding ATMs compromised with advanced new “shimming” devices made to steal data from chip card transactions. Authorities in the United States and abroad had seized many of these shimmers, but for years couldn’t decrypt the data on the devices. This is a story of ingenuity and happenstance, and how one former Secret Service agent helped crack a code that revealed the contours of a global organized crime ring.

Jeffrey Dant was a special agent at the U.S. Secret Service for 12 years until 2015. After that, Dant served as the global lead for the fraud fusion center at Citi, one of the largest financial institutions in the United States.

Not long after joining Citi, Dant heard from industry colleagues at a bank in Mexico who reported finding one of these shimming devices inside the card acceptance slot of a local ATM. As it happens, KrebsOnSecurity wrote about that particular shimmer back in August 2015.

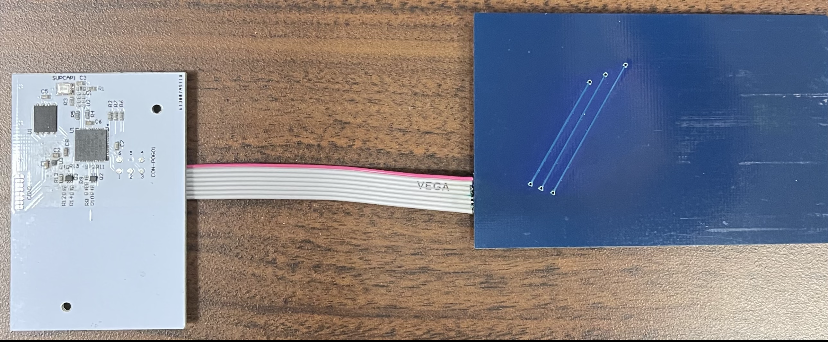

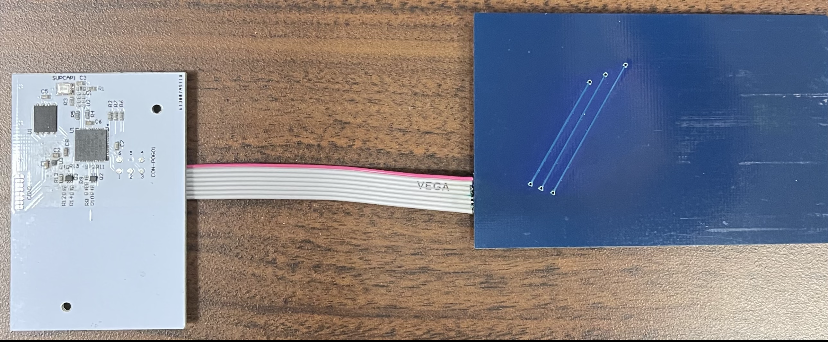

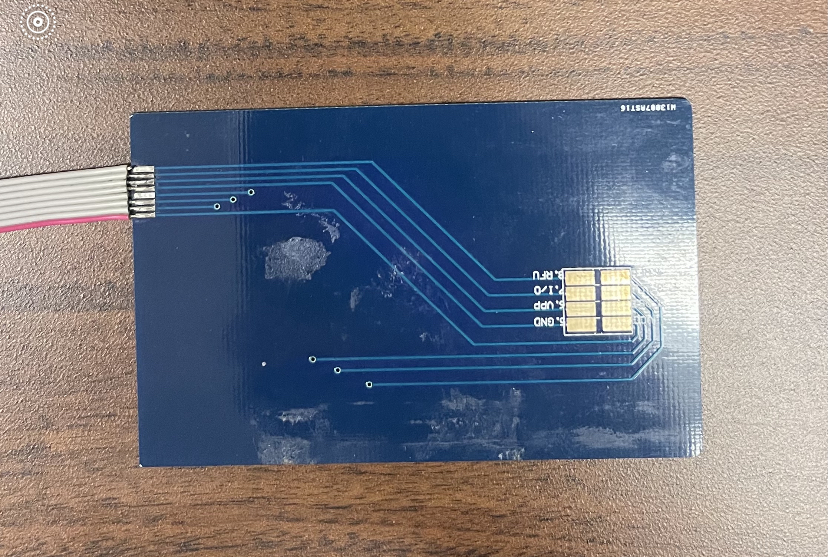

This card ‘shimming’ device is made to read chip-enabled cards and can be inserted directly into the ATM’s card acceptance slot.

The shimmers were an innovation that caused concern on multiple levels. For starters, chip-based payment cards were supposed to make it far more expensive and difficult for thieves to copy and clone. But these skimmers took advantage of weaknesses in the way many banks at the time implemented the new chip card standard.

Also, unlike traditional ATM skimmers that run on hidden cell phone batteries, the ATM shimmers found in Mexico did not require any external power source, and thus could remain in operation collecting card data until the device was removed.

When a chip card is inserted, a chip-capable ATM reads the data stored on the smart card by sending an electric current through the chip. Incredibly, these shimmers were able to siphon a small amount of that power (a few milliamps) to record any data transmitted by the card. When the ATM is no longer in use, the skimming device remains dormant, storing the stolen data in an encrypted format.

Dant and other investigators looking into the shimmers didn’t know at the time how the thieves who planted the devices went about gathering the stolen data. Traditional ATM skimmers are either retrieved manually, or they are programmed to transmit the stolen data wirelessly, such as via text message or Bluetooth.

But recall that these shimmers don’t have anywhere near the power needed to transmit data wirelessly, and the flexible shimmers themselves tend to rip apart when retrieved from the mouth of a compromised ATM. So how were the crooks collecting the loot?

“We didn’t know how they were getting the PINs at the time, either,” Dant recalled. “We found out later they were combining the skimmers with old school cameras hidden in fake overhead and side panels on the ATMs.”

Investigators wanted to look at the data stored on the shimmer, but it was encrypted. So they sent it to MasterCard’s forensics lab in the United Kingdom, and to the Secret Service.

“The Secret Service didn’t have any luck with it,” Dant said. “MasterCard in the U.K. was able to understand a little bit at a high level what it was doing, and they confirmed that it was powered by the chip. But the data dump from the shimmer was just encrypted gibberish.”

Organized crime gangs that specialize in deploying skimmers very often will encrypt stolen card data as a way to remove the possibility that any gang members might try to personally siphon and sell the card data in underground markets.

THE DOWNLOAD CARDS

Then in 2017, Dant got a lucky break: Investigators had found a shimming device inside an ATM in New York City, and that device appeared identical to the shimmers found in Mexico two years earlier.

“That was the first one that had showed up in the U.S. at that point,” Dant said.

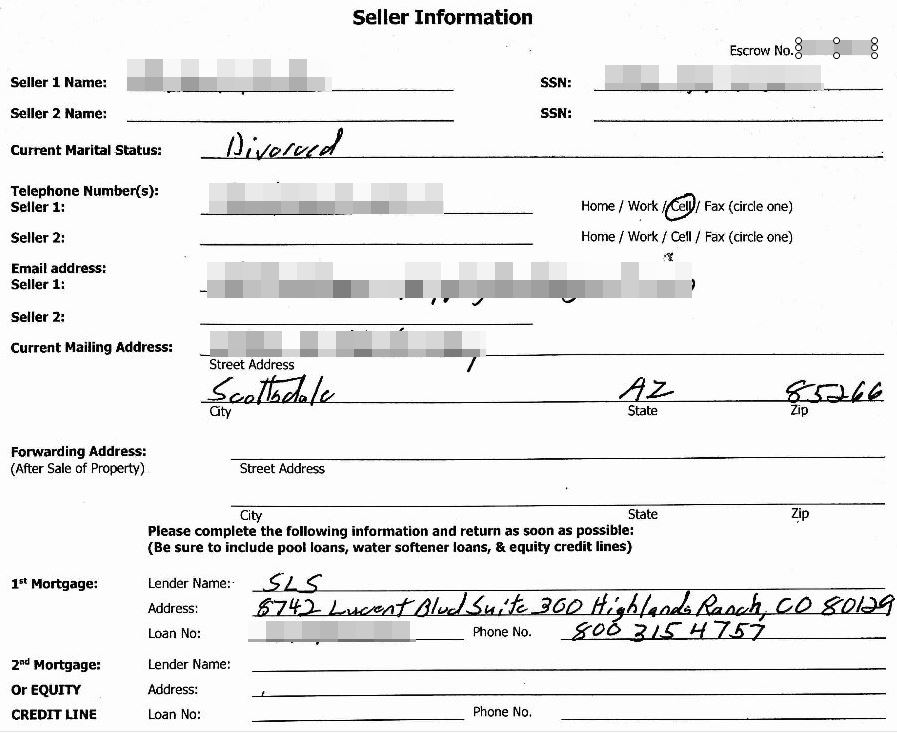

The Citi team suspected that if they could work backwards from the card data that was known to have been recorded by the skimmers, they might be able to crack the encryption.

“We knew when the shimmer went into the ATM, thanks to closed-circuit television footage,” Dant said. “And we know when that shimmer was discovered. So between that time period of a couple of days, these are the cards that interacted with the skimmer, and so these card numbers are most likely on this device.”

Based off that hunch, MasterCard’s eggheads had success decoding the encrypted gibberish. But they already knew which payment cards had been compromised, so what did investigators stand to gain from breaking the encryption?

According to Dant, this is where things got interesting: They found that the same primary account number (unique 16 digits of the card) was present on the download card and on the shimmers from both New York City and Mexican ATMs.

Further research revealed that account number was tied to a payment card issued years prior by an Austrian bank to a customer who reported never receiving the card in the mail.

“So why is this Austrian bank card number on the download card and two different shimming devices in two different countries, years apart?” Dant said he wondered at the time.

He didn’t have to wait long for an answer. Soon enough, the NYPD brought a case against a group of Romanian men suspected of planting the same shimming devices in both the U.S. and Mexico. Search warrants served against the Romanian defendants turned up multiple copies of the shimmer they’d seized from the compromised ATMs.

“They found an entire ATM skimming lab that had different versions of that shimmer in untrimmed squares of sheet metal,” Dant said. “But but what stood out the most was this unique device — the download card.”

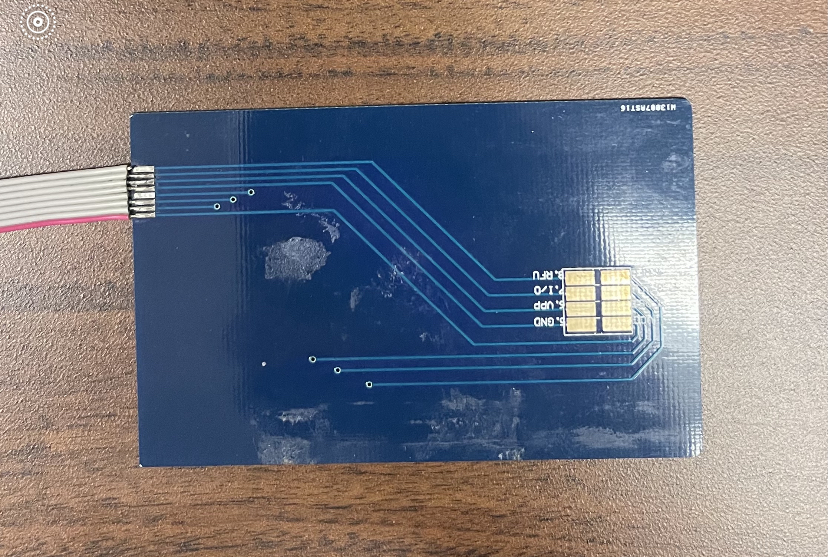

The download card (right, in blue) opens an encrypted session with the shimmer, and then transmits the stolen card data to the attached white plastic device. Image: KrebsOnSecurity.com.

The download card consisted of two pieces of plastic about the width of a debit card but a bit long longer. The blue plastic part — made to be inserted into a card reader — features the same contacts as a chip card. The blue plastic was attached via a ribbon cable to a white plastic card with a green LED and other electronic components.

Sticking the blue download card into a chip reader revealed the same Austrian card number seen on the shimming devices. It then became very clear what was happening.

“The download card was hard coded with chip card data on it, so that it could open up an encrypted session with the shimmer,” which also had the same card data, Dant said.

The download card, up close. Image: KrebsOnSecurity.com.

Once inserted into the mouth of ATM card acceptance slot that’s already been retrofitted with one of these shimmers, the download card causes an encrypted data exchange between it and the shimmer. Once that two-way handshake is confirmed, the white device lights up a green LED when the data transfer is complete.

THE MASTER KEY

Dant said when the Romanian crew mass-produced their shimming devices, they did so using the same stolen Austrian bank card number. What this meant was that now the Secret Service and Citi had a master key to discover the same shimming devices installed in other ATMs.

That’s because every time the gang compromised a new ATM, that Austrian account number would traverse the global payment card networks — telling them exactly which ATM had just been hacked.

“We gave that number to the card networks, and they were able to see all the places that card had been used on their networks before,” Dant said. “We also set things up so we got alerts anytime that card number popped up, and we started getting tons of alerts and finding these shimmers all over the world.”

For all their sleuthing, Dant and his colleagues never really saw shimming take off in the United States, at least nowhere near as prevalently as in Mexico, he said.

The problem was that many banks in Mexico and other parts of Latin America had not properly implemented the chip card standard, which meant thieves could use shimmed chip card data to make the equivalent of old magnetic stripe-based card transactions.

By the time the Romanian gang’s shimmers started showing up in New York City, the vast majority of U.S. banks had already properly implemented chip card processing in such a way that the same phony chip card transactions which sailed through Mexican banks would simply fail every time they were tried against U.S. institutions.

“It never took off in the U.S., but this kind of activity went on like wildfire for years in Mexico,” Dant said.

The other reason shimming never emerged as a major threat for U.S. financial institutions is that many ATMs have been upgraded over the past decade so that their card acceptance slots are far slimmer, Dant observed.

“That download card is thicker than a lot of debit cards, so a number of institutions were quick to replace the older card slots with newer hardware that reduced the height of a card slot so that you could maybe get a shimmer and a debit card, but definitely not a shimmer and one of these download cards,” he said.

Shortly after ATM shimmers started showing up at banks in Mexico, KrebsOnSecurity spent four days in Mexico tracing the activities of a Romanian organized crime gang that had very recently started its own ATM company there called Intacash.

Sources told KrebsOnSecurity that the Romanian gang also was paying technicians from competing ATM providers to retrofit cash machines with Bluetooth-based skimmers that hooked directly up to the electronics on the inside. Hooked up to the ATM’s internal power, those skimmers could collect card data indefinitely, and the data could be collected wirelessly with a smart phone.

Follow-up reporting last year by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) found Intacash and its associates compromised more than 100 ATMs across Mexico using skimmers that were able to remain in place undetected for years. The OCCRP, which dubbed the Roomanian group “The Riviera Maya Gang,” estimates the crime syndicate used cloned card data and stolen PINs to steal more than $1.2 billion from bank accounts of tourists visiting the region.

Last month, Mexican authorities arrested Florian “The Shark” Tudor, Intacash’s boss and the reputed ringleader of the Romanian skimming syndicate. Authorities charged that Tudor’s group also specialized in human trafficking, which allowed them to send gang members to compromise ATMs across the border in the United States.