Breach at Sabre Corp.’s Hospitality Unit

mardi 2 mai 2017 à 20:41Breaches involving major players in the hospitality industry continue to pile up. Today, travel industry giant Sabre Corp. disclosed what could be a significant breach of payment and customer data tied to bookings processed through a reservations system that serves more than 32,000 hotels and other lodging establishments.

In a quarterly filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) today, Southlake, Texas-based Sabre said it was “investigating an incident of unauthorized access to payment information contained in a subset of hotel reservations processed through our Hospitality Solutions SynXis Central Reservations system.”

In a quarterly filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) today, Southlake, Texas-based Sabre said it was “investigating an incident of unauthorized access to payment information contained in a subset of hotel reservations processed through our Hospitality Solutions SynXis Central Reservations system.”

According to Sabre’s marketing literature, more than 32,000 properties use Sabre’s SynXis reservations system, described as an inventory management Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) application that “enables hoteliers to support a multitude of rate, inventory and distribution strategies to achieve their business goals.”

Sabre said it has engaged security forensics firm Mandiant to support its investigation, and that it has notified law enforcement.

“The unauthorized access has been shut off and there is no evidence of continued unauthorized activity,” reads a brief statement that Sabre sent to affected properties today. “There is no reason to believe that any other Sabre systems beyond SynXis Central Reservations have been affected.”

Sabre’s software, data, mobile and distribution solutions are used by hundreds of airlines and thousands of hotel properties to manage critical operations, including passenger and guest reservations, revenue management, flight, network and crew management. Sabre also operates a leading global travel marketplace, which processes more than $110 billion of estimated travel spend annually by connecting travel buyers and suppliers.

Sabre told customers that it didn’t have any additional details about the breach to share at this time, so it remains unclear what the exact cause of the breach may be or for how long it may have persisted.

A card involving traveler transactions for even a small percentage of the 32,000 properties that are using Sabre’s impacted technology could jeopardize a significant number of customer credit cards in a short amount of time.

The news comes amid revelations about a blossoming breach at Intercontinental Hotel Group (IHG), the parent company that manages some 5,000 hotels worldwide, including Holiday Inn and Holiday Inn Express.

KrebsOnSecurity first reported in December 2016 that cards used at IHG properties were being sold to fraudsters, but it took until February 2017 for IHG to announce it had found malicious software installed at front-desk systems at just a dozen of its properties. On April 18, IHG disclosed in an update on the investigation that more than 1,200 properties were affected, and that there could well be more added in the coming days.

According to Verizon‘s latest annual Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR), malware attacks on point-of-sale systems used at front desk and hotel restaurant systems “are absolutely rampant” in the hospitality sector. Accommodation was the top industry for point-of-sale intrusions in this year’s data, with 87% of breaches within that pattern.

“Apparently, it is not only The Eagles that are destined for a long stay at the hotel,” Verizon mused in its report. “The hackers continue to be checked in indefinitely as well. Breach timelines continue to paint a rather dismal picture—with time-to-compromise being only seconds, time-to-exfiltration taking days, and times to discovery and containment staying firmly in the months camp.”

Card-stealing cyber thieves have broken into some of the largest hotel chains over the past few years. Hotel brands that have acknowledged card breaches over the last year after prompting by KrebsOnSecurity include Kimpton Hotels, Trump Hotels (twice), Hilton, Mandarin Oriental, and White Lodging (twice). Card breaches also have hit hospitality chains Starwood Hotels and Hyatt.

In many of those incidents, thieves planted malicious software on the point-of-sale devices at restaurants and bars inside of the hotel chains. Point-of-sale based malware has driven most of the credit card breaches over the past two years, including intrusions at Target and Home Depot, as well as breaches at a slew of point-of-sale vendors. The malicious code usually is installed via hacked remote administration tools. Once the attackers have their malware loaded onto the point-of-sale devices, they can remotely capture data from each card swiped at that cash register.

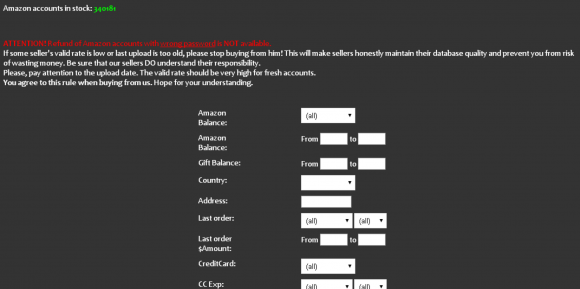

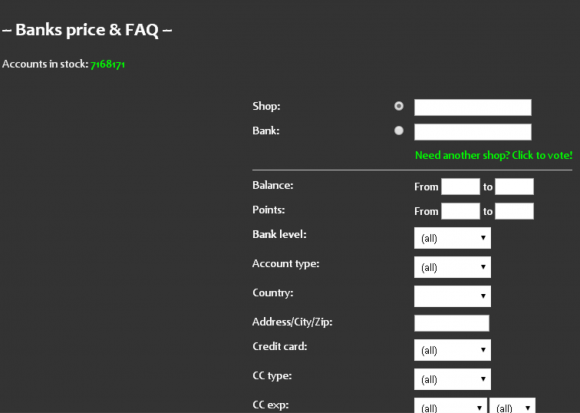

Thieves can then sell that data to crooks who specialize in encoding the stolen data onto any card with a magnetic stripe, and using the cards to purchase high-priced electronics and gift cards from big-box stores like Target and Best Buy.

Readers should remember that they’re not liable for fraudulent charges on their credit or debit cards, but they still have to report the unauthorized transactions. There is no substitute for keeping a close eye on your card statements. Also, consider using credit cards instead of debit cards; having your checking account emptied of cash while your bank sorts out the situation can be a hassle and lead to secondary problems (bounced checks, for instance).

![The 2pac[dot]cc credit card shop that Seleznov operated.](./media/c5452f55.2packcc-600x365.png)

![A private mesasge between card merchant "Bulba" and an interested buyer on the fraud bazaar carder[dot]pro.](./media/3d17db45.bulbaoncarder-600x401.png)