Think You’ve Got Your Credit Freezes Covered? Think Again.

mercredi 9 mai 2018 à 15:36I spent a few days last week speaking at and attending a conference on responding to identity theft. The forum was held in Florida, one of the major epicenters for identity fraud complaints in United States. One gripe I heard from several presenters was that identity thieves increasingly are finding ways to open new lines of credit for things like mobile phones on people who have already frozen their credit files with the big-three credit bureaus. Here’s a look at what may be going on, and how you can protect yourself.

Carrie Kerskie is director of the Identity Fraud Institute at Hodges University in Naples, and a big part of her job is helping local residents respond to identity theft and identity fraud complaints. Kerskie said she’s had multiple victims in her area recently complain of having cell phone accounts opened in their names even though they had already frozen their credit files at the big three credit bureaus — Equifax, Experian and Trans Union (as well as distant fourth bureau Innovis).

The freeze process is designed so that creditor should not be able to pull a copy of your report unless you unfreeze the account. A credit freeze blocks potential creditors from being able to view or “pull” your credit file, making it far more difficult for identity thieves to apply for new lines of credit in your name.

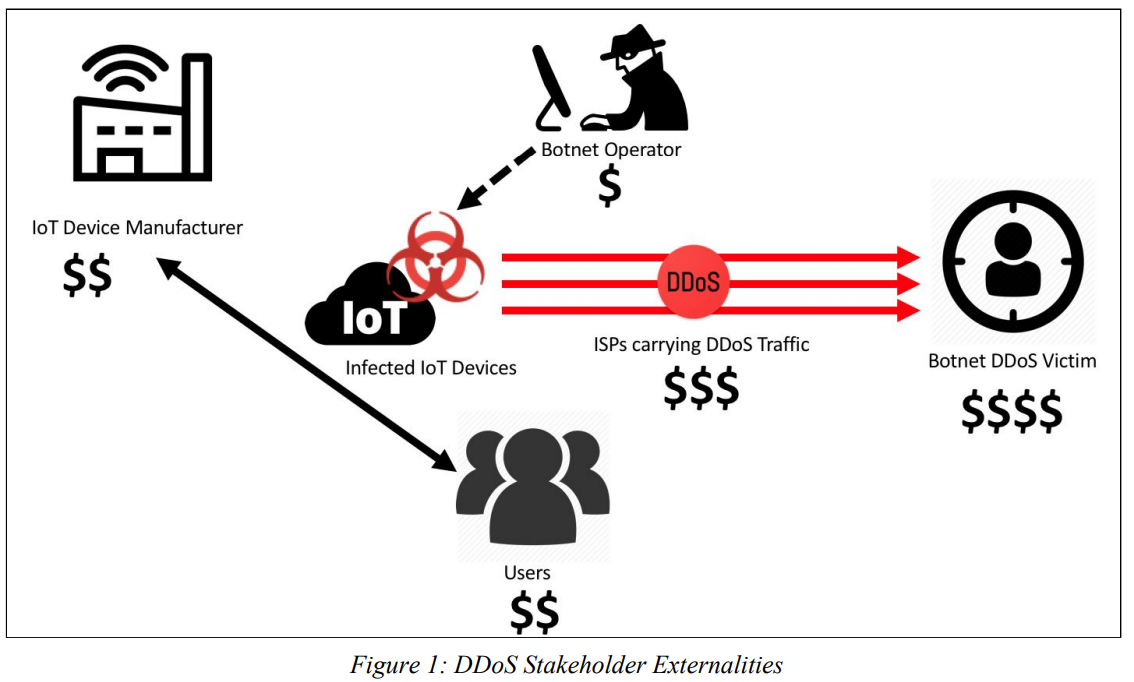

A freeze works to protect one’s credit file only if a potential creditor (or ID thief) tries to open a new line of credit at a company that uses one of the big three bureaus or Innovis. But Kerskie’s investigation revealed that the mobile phone merchants weren’t asking any of those four credit bureaus. Rather, the mobile providers that dinged the credit of Kerskie’s clients instead were making consumer credit queries with the National Consumer Telecommunications and Utilities Exchange (NCTUE), or nctue.com.

Source: nctue.com

“We’re finding that a lot of phone carriers — even some of the larger ones — are relying on NCTUE for credit checks,” Kerskie said. “Phone carriers, utilities, power, water, cable, any of those. They’re all starting to use this more.”

The NCTUE is a consumer reporting agency founded by mobile provider AT&T in 1997 that maintains data such as payment and account history, reported by telecommunication, pay TV and utility service providers that are members of NCTUE.

Who are the NCTUE’s members? If you call the 800-number that NCTUE makes available to get a free copy of your NCTUE credit report, the option for “more information” about the organization says there are four “exchanges” that feed into the NCTUE’s system: the NCTUE itself; something called “Centralized Credit Check Systems“; the New York Data Exchange; and the California Utility Exchange.

According to a partner solutions page at Verizon, the New York Data Exchange is a not-for-profit created in 1996 that provides participating local exchange carriers with access to local telecommunications service arrears (accounts that are unpaid) and final account information on residential end user accounts. The NYDE is operated by Equifax Credit Information Services Inc. (yes, that Equifax). Verizon is one of many telecom providers that use the NYDE (and recall that AT&T was the founder of NCTUE).

The California Utility Exchange collects customer payment data from dozens of local utilities in the state, and also is operated by Equifax (Equifax Information Services LLC).

Google has virtually no useful information available about an entity called Centralized Credit Check Systems. If anyone finds differently, please leave a note in the comments section.

When I did some more digging on the NCTUE, I discovered…wait for it…Equifax also is the sole contractor that manages the NCTUE database. The entity’s site is also hosted out of Equifax’s servers. Equifax’s current contract to provide this service expires in 2020, according to a press release posted in 2015 by Equifax.

RED LIGHT. GREEN LIGHT. RED LIGHT.

Fortunately, the NCTUE makes it fairly easy to obtain any records they may have on you. Simply phone them up at 1-866-349-5185 and provide your Social Security number and the numeric portion of your registered street address.

Assuming it can verify you with that information, the system then orders a credit report to be sent to the address on file. You can also request to be sent a free “risk score” assigned by the NCTUE for each credit file it maintains.

The NCTUE also offers a free online process for freezing one’s report. Perhaps unsurprisingly, however, the process for ordering a freeze through the NCTUE appears to be completely borked at the moment, thanks no doubt to Equifax’s well documented abysmal security practices.

Or it could all be part of a willful and negligent strategy to continue discouraging Americans from freezing their credit files.

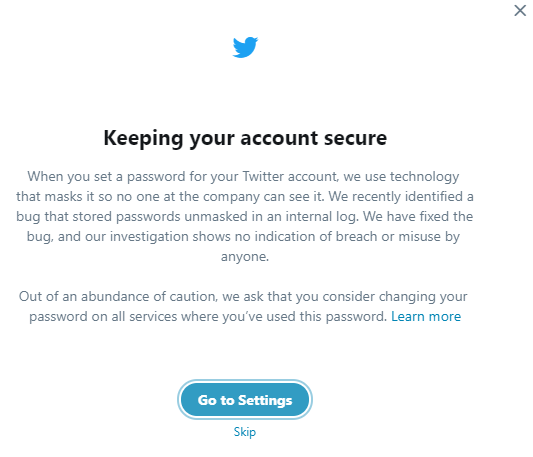

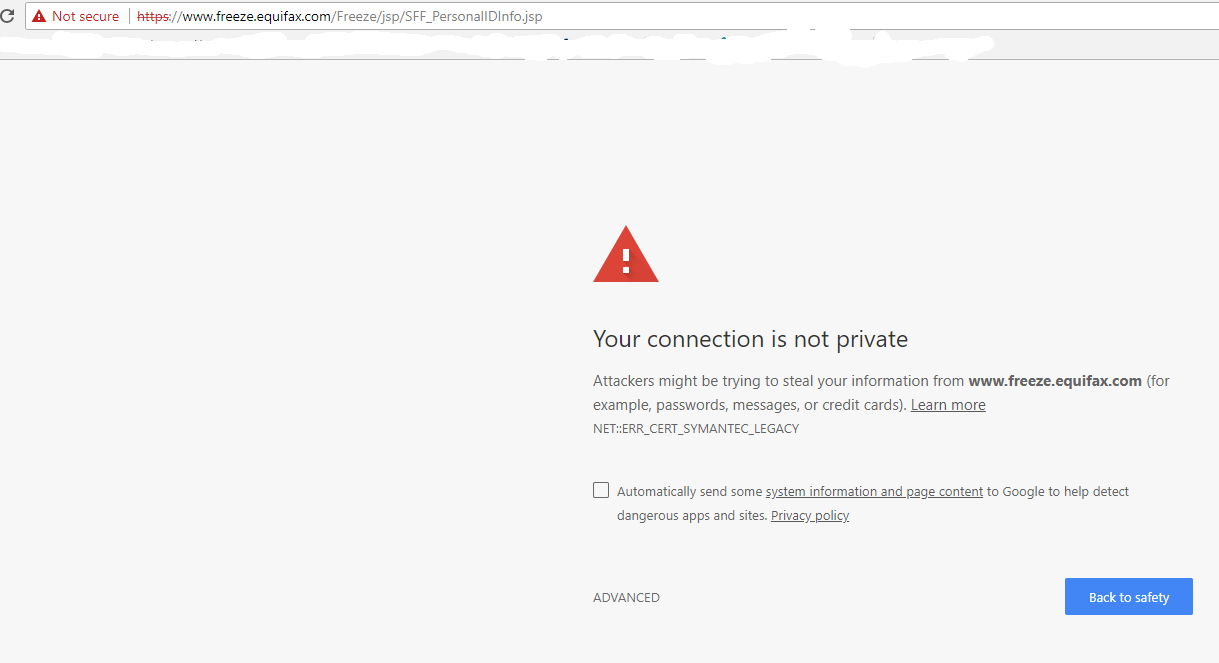

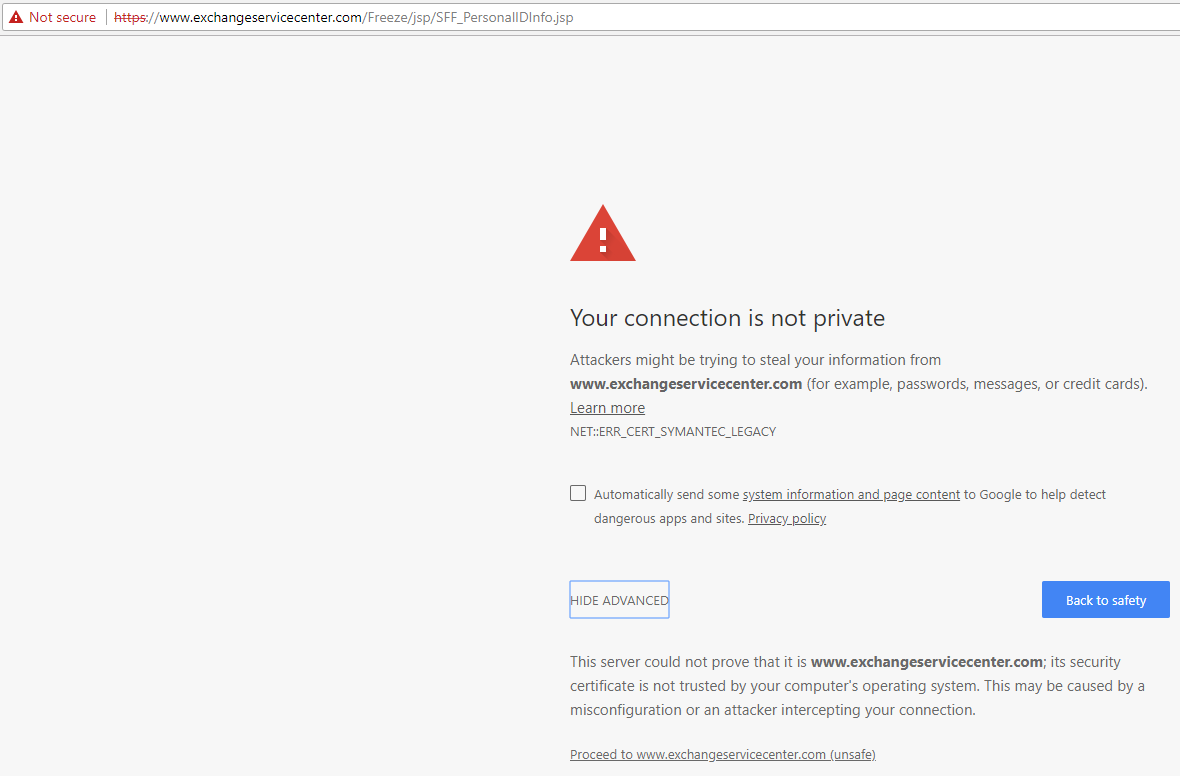

On April 29, I had an occasion to visit Equifax’s credit freeze application page, and found that the site was being served with an expired SSL encryption certificate from Symantec. This happened because I browsed the site using Google Chrome, and Google announced a decision in September 2017 to no longer trust SSL certs issued by Symantec prior to June 1, 2016. Google said it would do this starting with Google Chrome version 66. It did not keep this plan a secret.

On April 18, Google pushed out Chrome 66. Despite all of the advance warnings, the security people at Equifax apparently missed the memo and in so doing probably scared most people away from its freeze page for several weeks (Equifax fixed the problem on its site sometime after I tweeted about the borked certificate on April 29). That’s because when one uses Chrome to visit a site whose encryption certificate is validated by one of these unsupported Symantec certs, Chrome puts up a dire security warning that would almost certainly discourage most casual users from continuing.

The insecurity around Equifax’s own freeze site likely discouraged people from requesting a freeze on their credit files.

On May 7, when I visited the NCTUE’s page for freezing my credit file with them I was presented with the very same connection SSL security alert from Chrome, warning that any data I share with the NCTUE’s freeze page might not be encrypted in transit.

The security alert generated by Chrome when visiting the freeze page for the NCTUE, whose database (and apparently web site) also is run by Equifax.

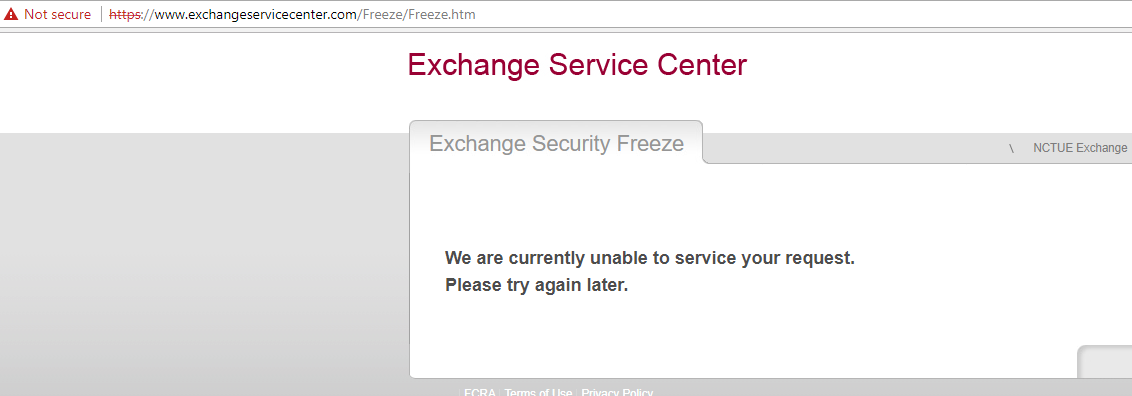

When I clicked through past the warnings and proceeded to the insecure NCTUE freeze form (which is worded and stylized almost exactly like Equifax’s credit freeze page and is hosted on Equifax’s own servers), I filled out the required information to freeze my NCTUE file. No dice. I was unceremoniously declined the opportunity to do that. “We are currently unable to service your request,” read the resulting Web page, without suggesting alternative means of obtaining its report. “Please try again later.”

The message I received after trying to freeze my file with the NCTUE.

This scenario will no doubt be familiar to many readers who tried (and failed in a similar fashion) to file freezes on their credit files with Equifax after the company divulged that hackers had relieved it of Social Security numbers, addresses, dates of birth and other sensitive data on nearly 150 million Americans last September. I attempted to file a freeze via the NCTUE’s site with no fewer than three different browsers, and each time the form reset itself upon submission or took me to a failure page.

So let’s review. Many people who have succeeded in freezing their credit files with Equifax have nonetheless had their identities stolen and new accounts opened in their names thanks to a lesser-known credit bureau that seems to rely entirely on credit checking entites operated by Equifax.

“This just reinforces the fact that we are no longer in control of our information,” said Kerskie, who is also a founding member of Griffon Force, a Florida-based identity theft restoration firm.

I find it difficult to disagree with Kerskie’s statement. What chaps me about this discovery is that countless Americans are in many cases plunking down $2-$10 per bureau to freeze their credit files, and yet a huge player in this market is able to continue to profit off of identity theft on those same Americans.

EQUIFAX RESPONDS

I reached out to Equifax to understand why the credit bureau operating the NCTUE’s data exchange (and those of at least two other contributing members) couldn’t detect when consumers had placed credit freezes with Equifax. As you might imagine, Equifax responded that NCTUE is separate entity from Equifax. It also said NCTUE doesn’t include Equifax credit information.

Here is Equifax’s full statement on the matter:

· The National Consumer Telecom and Utilities Exchange, Inc. (NCTUE) is a nationwide, member-owned and operated, FCRA-compliant consumer reporting agency that houses both positive and negative consumer payment data reported by its members, such as new connect requests, payment history, and historical account status and/or fraudulent accounts. NCTUE members are providers of telecommunications and pay/satellite television services to consumers, as well as utilities providing gas, electrical and water services to consumers.

· This information is available to NCTUE members and, on a limited basis, to certain other customers of NCTUE’s contracted exchange operator, Equifax Information Services, LLC (Equifax) – typically financial institutions and insurance providers. NCTUE does not include Equifax credit information, and Equifax is not a member of NCTUE, nor does Equifax own any aspect of NCTUE. NCTUE does not provide telecommunications pay/ satellite television or utility services to consumers, and consumers do not apply for those services with NCTUE.

· As a consumer reporting agency, NCTUE places and lifts security freezes on consumer files in accordance with the state law applicable to the consumer. NCTUE also maintains a voluntary security freeze program for consumers who live in states which currently do not have a security freeze law.

· NCTUE is a separate consumer reporting agency from Equifax and therefore a consumer would need to independently place and lift a freeze with NCTUE.

· While state laws vary in the manner in which consumers can place or lift a security freeze (temporarily or permanently), if a consumer has a security freeze on his or her NCTUE file and has not temporarily lifted the freeze, a creditor or other service provider, such as a mobile phone provider, generally cannot access that consumer’s NCTUE report in connection with a new account opening. However, the creditor or provider may be able to access that consumer’s credit report from another consumer reporting agency in order to open a new account, or decide to open the account without accessing a credit report from any consumer reporting agency, such as NCTUE or Equifax.

PLACING THE FREEZE

I was finally able to successfully place a freeze on my NCTUE report by calling their 800-number — 1-866-349-5355. The message said the NCTUE might charge a fee for placing or lifting the freeze, in accordance with state freeze laws.

Depending on your state of residence, the cost of placing a freeze on your credit file at Equifax, Experian or Trans Union can run between $3 and $10 per credit bureau, and in many states the bureaus also can charge fees for temporarily “thawing” and removing a freeze (according a list published by Consumers Union, residents of four states — Indiana, Maine, North Carolina, South Carolina — do not need to pay to place, thaw or lift a freeze).

While my home state of Virginia allows the bureaus to charge $10 to place a freeze, for whatever reason the NCTUE did not assess that fee when I placed my freeze request with them. When and if your freeze request does get approved using the NCTUE’s automated phone system, make sure you have pen and paper or a keyboard handy to jot down the freeze PIN, which you will need in the event you ever wish to lift the freeze. When the system read my freeze PIN, it was read so quickly that I had to hit “*” on the dial pad several times to repeat the message.

It’s frankly laughable that consumers should ever have to pay to freeze their credit files at all, and yet a recent study indicates that almost 20 percent of Americans chose to do so at one or more of the three major credit bureaus since Equifax announced its breach last fall. The total estimated cost to consumers in freeze fees? $1.4 billion. With a freeze on your files, the major credit bureaus stand to lose about one dollar for each time they might have been able to sell your credit report to a potential creditor, or potential identity thief.

But wishing Equifax and its ilk were finally and completely exposed for the digital dinosaurs that they are will not change the fact that if you care about your identity, you now may have another freeze to worry about. If you decide to take this step, please sound off about your experience in the comments below.

First, the

First, the  For Windows users with Mozilla Firefox installed, the browser prompts users to enable Flash on a per-site basis.

For Windows users with Mozilla Firefox installed, the browser prompts users to enable Flash on a per-site basis.