A chief criticism I heard from readers of my book, Spam Nation: The Inside Story of Organized Cybercrime, was that it dealt primarily with petty crooks involved in petty crimes, while ignoring more substantive security issues like government surveillance and cyber war. But now it appears that the chief antagonist of Spam Nation is at the dead center of an international scandal involving the hacking of U.S. state electoral boards in Arizona and Illinois, the sacking of Russia’s top cybercrime investigators, and the slow but steady leak of unflattering data on some of Russia’s most powerful politicians.

Sergey Mikhaylov

In a major shakeup that could have lasting implications for transnational cybercrime investigations, it’s emerged that Russian authorities last month arrested Sergey Mikhaylov — the deputy chief of the country’s top anti-cybercrime unit — as well as Ruslan Stoyanov, a senior employee at Russian security firm Kaspersky Lab.

In a statement released to media, Kaspersky said the charges against Stoyanov predate his employment at the company beginning in 2012. Prior to Kaspersky, Stoyanov served as deputy director at a cybercrime investigation firm called Indrik, and before that as a major in the Russian Ministry of Interior’s Moscow Cyber Crime Unit.

In a move straight out of a Russian spy novel, Mikhaylov reportedly was arrested while in the middle of a meeting, escorted out of the room with a bag thrown over his head. Both men are being tried for treason. As a result, the government’s case against them is classified, and it’s unclear exactly what they are alleged to have done.

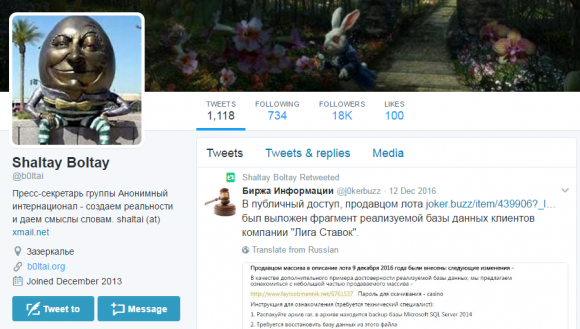

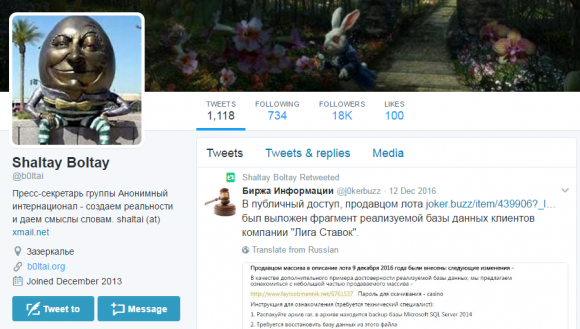

However, many Russian media outlets now report that the men are suspected of leaking information to Western investigators about investigations, and of funneling personal and often embarrassing data on Russia’s political elite to a popular blog called Humpty Dumpty (Шалтай-Болтай).

According to information obtained by KrebsOnSecurity, the arrests may very well be tied to a long-running grudge held by Pavel Vrublevsky, a Russian businessman who for years paid most of the world’s top spammers and virus writers to pump malware and hundreds of billions of junk emails into U.S. inboxes.

The Twitter page of the blog Shaltay Boltay (Humpty Dumpty).

In September 2016, Arlington, Va.-based security firm ThreatConnect published a report that included Internet addresses that were used as staging grounds in the U.S. state election board hacks [full disclosure: ThreatConnect has been an advertiser on this blog]. That report was based in part on an August 2016 alert from the FBI (PDF), and noted that most of the Internet addresses were assigned to a Russian hosting firm called King-Servers[dot]com.

King-Servers is owned by a 26-year-old Russian named Vladimir Fomenko. As I observed in this month’s The Download on the DNC Hack, Fomenko issued a statement in response to being implicated in the ThreatConnect and FBI reports. Fomenko’s statement — written in Russian — said he did not know the identity of the hackers who used his network to attack U.S. election-related targets, but that those same hackers still owed his company USD $290 in unpaid server bills.

A English-language translation of that statement was simultaneously published on ChronoPay.com, Vrublevsky’s payment processing company.

“The analysis of the internal data allows King Servers to confidently refute any conclusions about the involvement of the Russian special services in this attack,” Fomenko said in his statement, which credits ChronoPay for the translation. “The company also reported that the attackers still owe the company $US290 for rental services and King Servers send an invoice for the payment to Donald Trump & Vladimir Putin, as well as the company reserves the right to send it to any other person who will be accused by mass media of this attack.”

ChronoPay founder and owner Pavel Vrublevsky.

I mentioned Vrublevsky in that story because I knew Fomenko (a.k.a. “Die$el“) and he were longtime associates; both were prominent members of Crutop[dot]nu, a cybercrime forum that Vrublevsky (a.k.a. “Redeye“) owned and operated for years. In addition, I recognized Vrublevsky’s voice and dark humor in the statement, and thought it was interesting that Vrublevsky was inserting himself into all the alleged election-hacking drama.

That story also noted how common it was for Russian intelligence services to recruit Russian hackers who were already in prison — by commuting their sentences in exchange for helping the government hack foreign adversaries. In 2013, Vrublevsky was convicted of hiring his most-trusted spammer and malware writer to attack one of ChronoPay’s chief competitors, but he was inexplicably released a year earlier than his two-and-a-half year sentence required.

Meanwhile, the malware author that Vrublevsky hired to launch the attack which later landed them both in jail told The New York Times last month that he’d also been approached while in prison by someone offering to commute his sentence if he agreed to hack for the Russian government, but that he’d refused and was forced to serve out his entire sentence.

My book Spam Nation identified most of the world’s top spammers and virus writers by name, and I couldn’t have done that had someone in Russian law enforcement not leaked to me and to the FBI tens of thousands of email messages and documents stolen from ChronoPay’s offices.

To this day I don’t know the source of those stolen documents and emails. They included spreadsheets chock full of bank account details tied to some of the world’s most active cybercriminals, and to a vast network of shell corporations created by Vrublevsky and ChronoPay to help launder the proceeds from his pharmacy, spam and fake antivirus operations.

Fast-forward to this past week: Multiple Russian media outlets covering the treason case mention that King-Servers and its owner Fomenko rented the servers from a Dutch company controlled by Vrublevsky.

Both Fomenko and Vrublevsky deny this, but the accusations got me looking more deeply through my huge cache of leaked ChronoPay emails for any mention of Mikhaylov or Stoyanov — the cybercrime investigators arrested in Russia last week and charged with treason. I also looked because in phone interviews in 2011 Vrublevsky told me he suspected both men were responsible for leaking his company’s emails to me, to the FBI, and to Kimberly Zenz, a senior threat analyst who works for the security firm iDefense (now owned by Verisign).

In that conversation, Vrublevsky said he was convinced that Mikhaylov was taking information gathered by Russian government cybercrime investigators and feeding it to U.S. law enforcement and intelligence agencies and to Zenz. Vrublevsky told me then that if ever he could prove for certain Mikhaylov was involved in leaking incriminating data on ChronoPay, he would have someone “tear him a new asshole.”

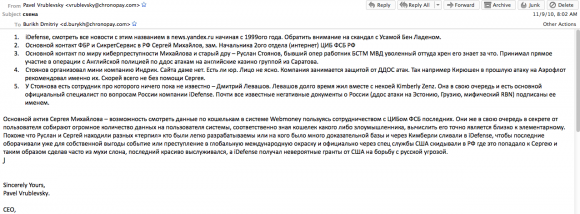

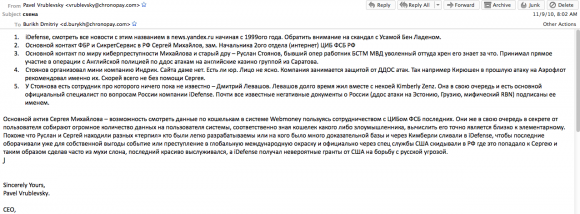

As it happens, an email that Vrublevsky wrote to a ChronoPay employee in 2010 eerily presages the arrests of Mikhaylov and Stoyanov, voicing Vrublevsky’s suspicion that the two men were closely involved in leaking ChronoPay emails and documents that were seized by Mikhaylov’s own division — the Information Security Center (CDC) of the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB). A copy of that email is shown in Russian in the screen shot below. A translated version of the message text is available here (PDF).

A copy of an email Vrublevsky sent to a ChronoPay co-worker about his suspicions that Mikhaylov and Stoyanov were leaking government secrets.

In it, Vrublevsky claims Zenz was dating a Russian man who worked with Stoyanov at Indrik — the company that both men worked at before joining Kaspersky — and that Stoyanov was feeding her privileged information about important Russian hackers.

“Looks like Sergey and Ruslan were looking for various ‘scapegoats’ who were easy to track down and who had a lot of criminal evidence collected against them, and then reported them to iDefense through Kimberly,” Vrublevsky wrote to a ChronoPay subordinate in an email dated Sept. 11, 2010. “This was done so that iDefense could get some publicity for themselves by turning this into a global news story. Then the matter was reported by US intelligence to Russia, and then got on Sergey’s desk who made a big deal out of it and then solved the case brilliantly, gaining favors with his bosses. iDefense at the same time was getting huge grants to fight Russian cyberthreats.”

Based on how long Vrublevsky has been trying to sell this narrative, it seems he may have finally found a buyer.

Verisign’s Zenz said she did date a Russian man who worked with Stoyanov, but otherwise called Vrublevsky’s accusations a fabrication. Zenz said she’s uncertain if Vrublevsky has enough political clout to somehow influence the filing of a treason case against the two men, but that she suspects the case has more to do with ongoing and very public recent infighting within the Russian FSB.

“It is hard for me imagine how Vrublevsky would be so powerful as to go after the people that investigated him on his own,” Zenz told KrebsOnSecurity. “Perhaps the infighting going on right now among the security forces already weakened Mikhaylov enough that Vrublevsky was able to go after him. Leaking communications or information to the US is a very extreme thing to have done. However, if it really did happen, then Mikhaylov would be very weak, which could explain how Vrublevsky would be able to go after him.”

Nevertheless, Zenz said, the Russian government’s treason case against Mikhaylov and Stoyanov is likely to have a chilling effect on the sharing of cyber threat information among researchers and security companies, and will almost certainly create problems for Kaspersky’s image abroad.

“This really weakens the relationship between Kaspersky and the FSB,” Zenz said. “It pushes Kaspersky to formalize relations and avoid the informal cooperation upon which cybercrime investigations often rely, in Russia and globally. It is also likely to have a chilling effect on such cooperation in Russia. This makes people ask, “If I share information on an attack or malware, can I be charged with treason?’”

Vrublevsky declined to comment for this story. King Servers’ Fomenko could not be immediately reached for comment.

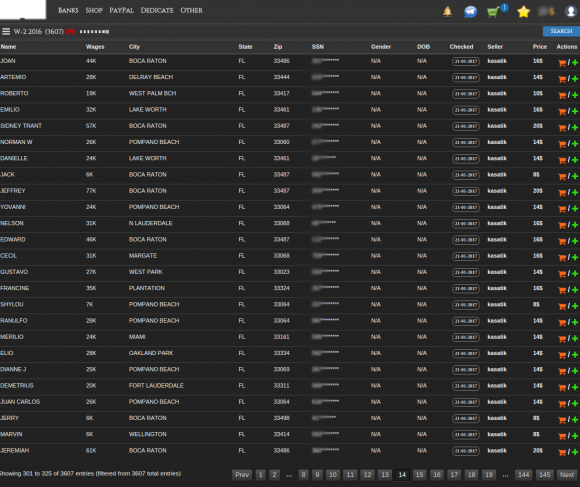

The IRS said phishers are off to a much earlier start this year than in tax years past, trying to siphon W-2 data that can be used to file fraudulent refund requests on behalf of taxpayers. The agency warned that thieves also appear to be targeting a wider range of organizations in these W-2 phishing schemes, including school districts, healthcare organizations, chain restaurants, temporary staffing agencies, tribal organizations and nonprofits.

The IRS said phishers are off to a much earlier start this year than in tax years past, trying to siphon W-2 data that can be used to file fraudulent refund requests on behalf of taxpayers. The agency warned that thieves also appear to be targeting a wider range of organizations in these W-2 phishing schemes, including school districts, healthcare organizations, chain restaurants, temporary staffing agencies, tribal organizations and nonprofits.