How Does One Get Hired by a Top Cybercrime Gang?

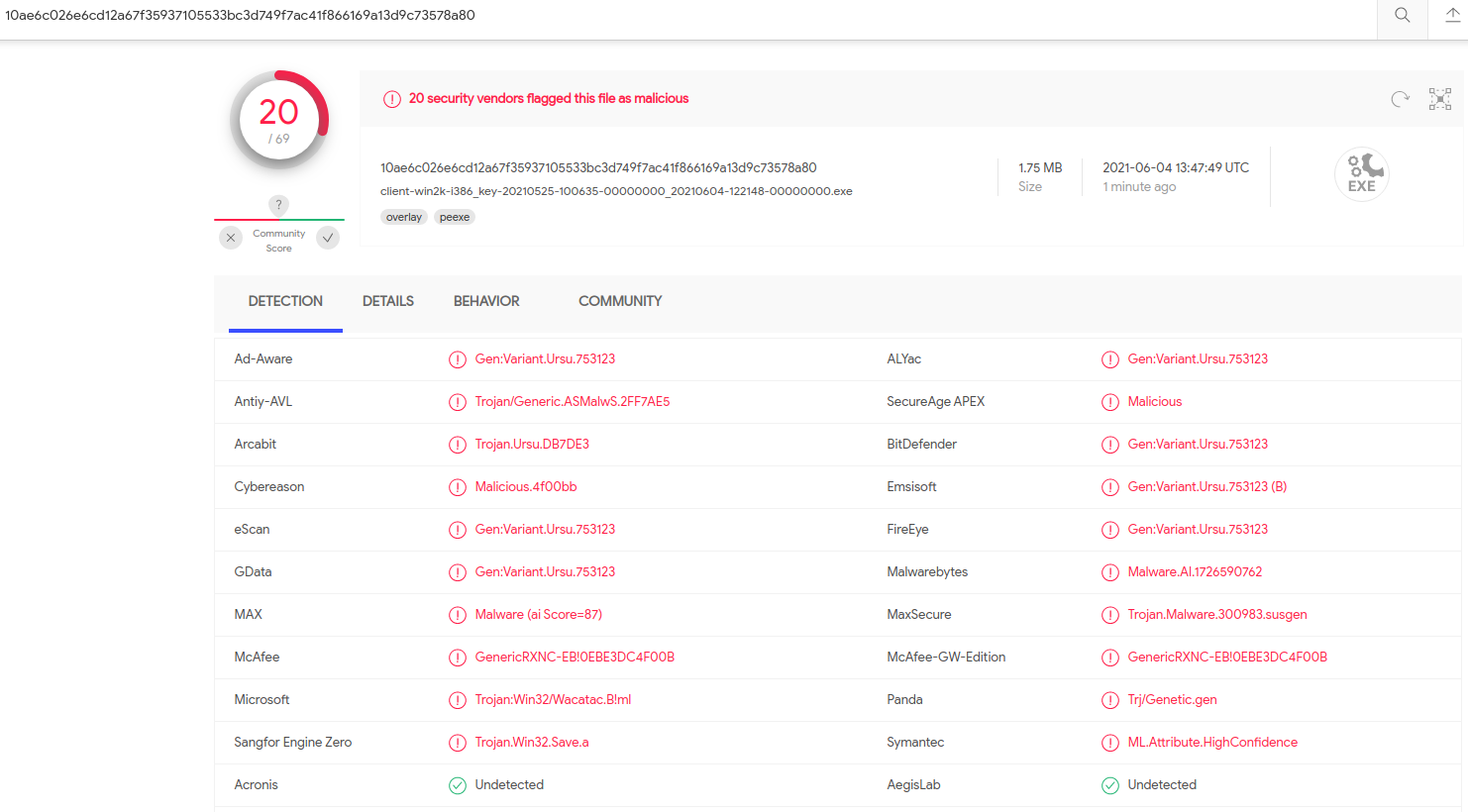

mardi 15 juin 2021 à 17:41The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) last week announced the arrest of a 55-year-old Latvian woman who’s alleged to have worked as a programmer for Trickbot, a malware-as-a-service platform responsible for infecting millions of computers and seeding many of those systems with ransomware.

Just how did a self-employed web site designer and mother of two come to work for one of the world’s most rapacious cybercriminal groups and then leave such an obvious trail of clues indicating her involvement with the gang? This post explores answers to those questions, as well as some of the ways Trickbot and other organized cybercrime gangs gradually recruit, groom and trust new programmers.

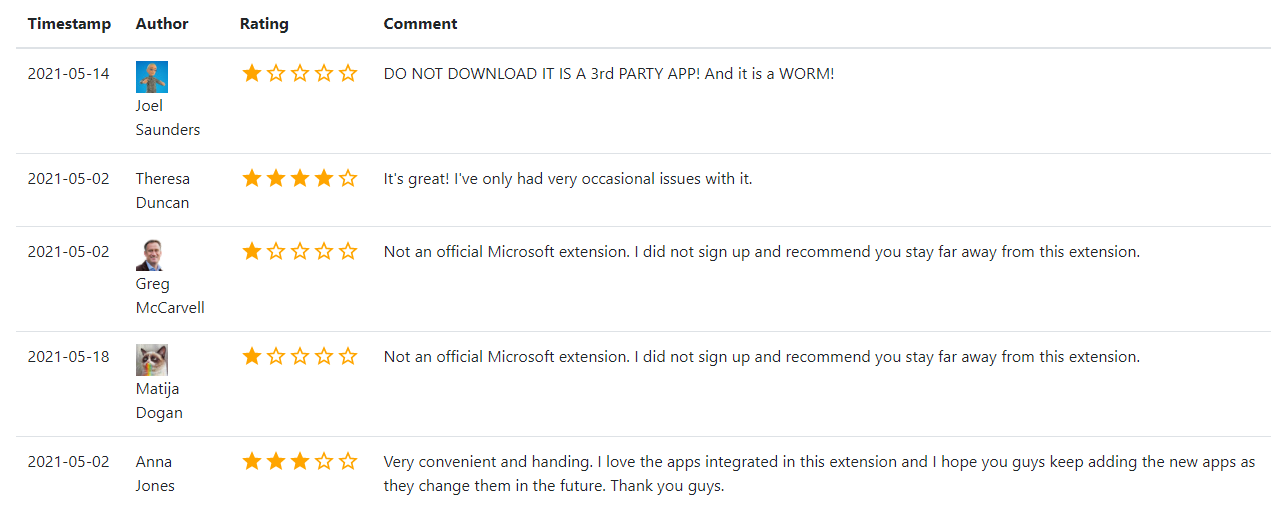

Alla Witte’s personal website — allawitte[.]nl — circa October 2018.

The indictment released by the DOJ (PDF) is heavily redacted, and only one of the defendants is named: Alla “Max” Witte, a 55-year-old Latvian national who was arrested Feb. 6 in Miami, Fla.

The DOJ alleges Witte was responsible for “overseeing the creation of code related to the monitoring and tracking of authorized users of the Trickbot malware, the control and deployment of ransomware, obtaining payments from ransomware victims, and developing tools and protocols for the storage of credentials stolen and exfiltrated from victims infected by Trickbot.”

The indictment also says Witte provided code to the Trickbot Group for a web panel used to access victim data stored in a database. According to the government, that database contained a large number of credit card numbers and stolen credentials from the Trickbot botnet, as well as information about infected machines available as bots.

“Witte provided code to this repository that showed an infected computer or ‘bot’ status in different colors based on the colors of a traffic light and allowed other Trickbot Group members to know when their co-conspirators were working on a particular infected machine,” the indictment alleges.

While any law enforcement action against a crime group that has targeted hospitals, schools, public utilities and governments is good news, Witte’s indictment and arrest were probably inevitable: It is hard to think of an accused cybercriminal who has made more stunningly poor and rookie operational security mistakes than this Latvian senior citizen.

For starters, it appears at one point in 2020 Witte actually hosted Trickbot malware on a vanity website registered in her name — allawitte[.]nl.

While it is generally a bad idea for cybercriminals to mix their personal life with work, Witte’s social media accounts mention a close family member (perhaps her son or husband) had the first name “Max,” which allegedly was her hacker handle.

Unlike many accused cybercriminals who hail from Russia or former Soviet countries, Witte did not feel obligated to avoid traveling to areas where she might be within reach of U.S. law enforcement agencies. According to her indictment, Witte was living in the South American nation of Suriname and she was arrested in Miami while flying from Suriname. It is not clear where her intended destination was.

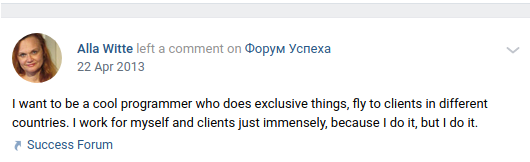

A Google-translated post Witte made to her Vkontakte page, five years before allegedly joining the Trickbot group.

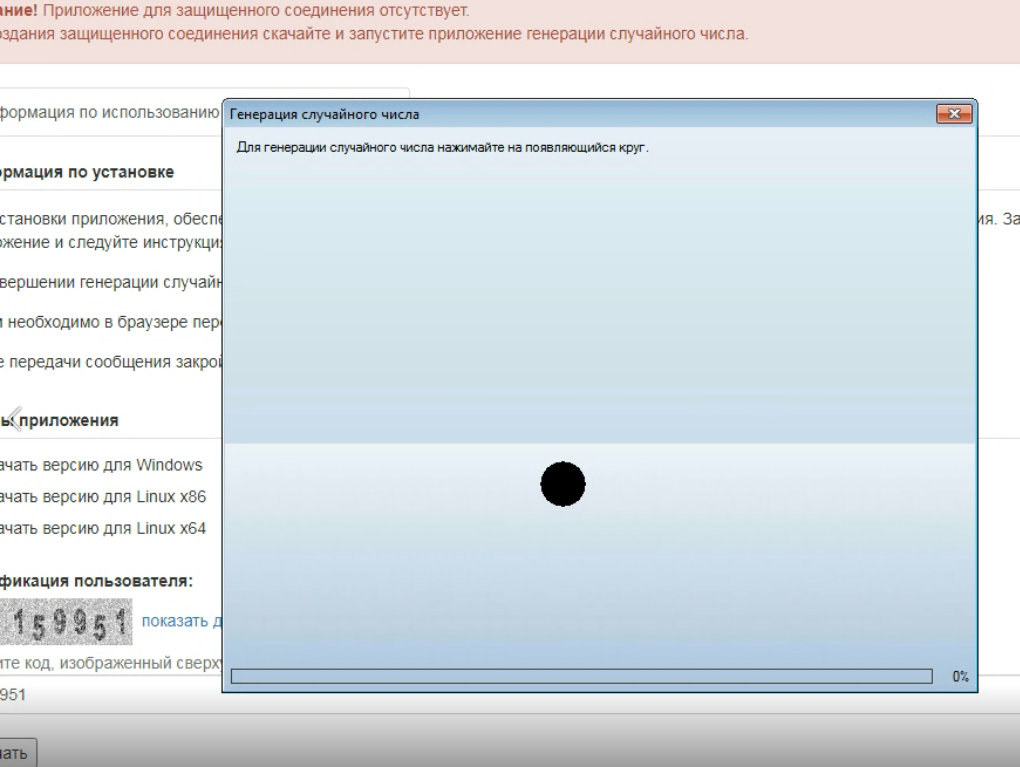

Alex Holden, founder of the cybersecurity intelligence firm Hold Security, said Witte’s greatest lapse in judgment came around Christmas time in 2019, when she infected one of her own computers with the Trickbot malware — allowing it to steal and log her data within the botnet interface.

“On top of the password re-use, the data shows a great insight into her professional and personal Internet usage,” Holden wrote in a blog post on Witte’s arrest.

“Many in the gang not only knew her gender but her name too,” Holden wrote. “Several group members had AllaWitte folders with data. They refer to Alla almost like they would address their mothers.”

So how did this hacker mom with apparently zero sense of self-preservation come to work for one of the world’s most predatory cybercriminal gangs?

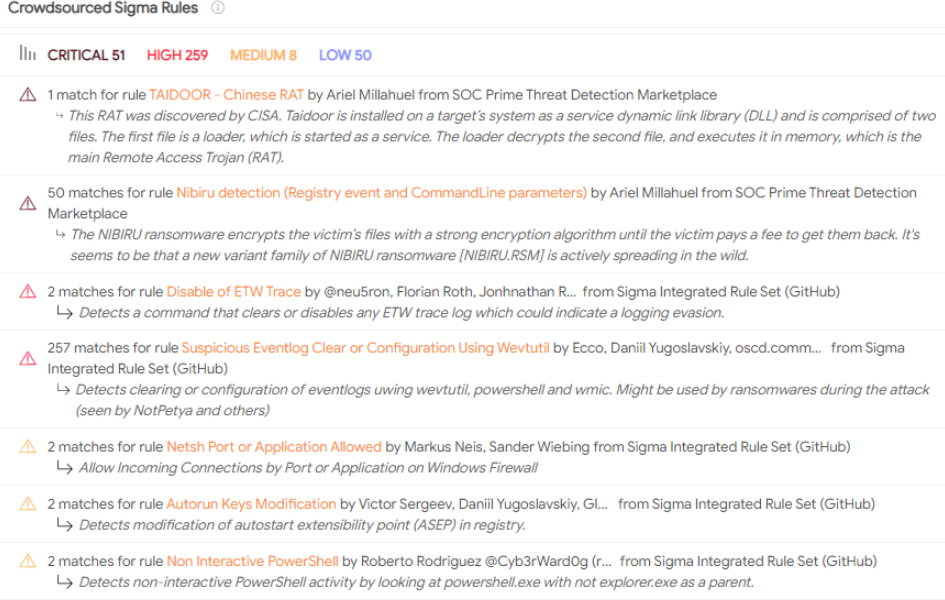

The government’s indictment dedicates several pages to describing the hiring processes of the Trickbot group, which continuously scoured fee-based Russian and Belarussian-based job websites for resumes of programmers looking for work. Those who responded were asked to create various programs designed to test the applicant’s problem-solving and coding skills.

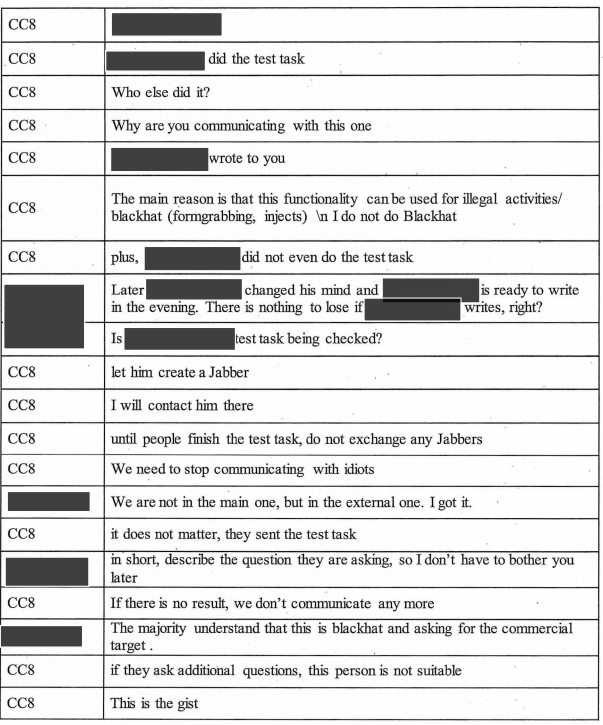

Here’s a snippet of translated instant message text between two of the unnamed Trickbot defendants, in which they discuss an applicant who understood immediately that he was being hired to help with cybercrime activity.

A conversation between two Trickbot group members concerning a potential new hire. Image: DOJ.

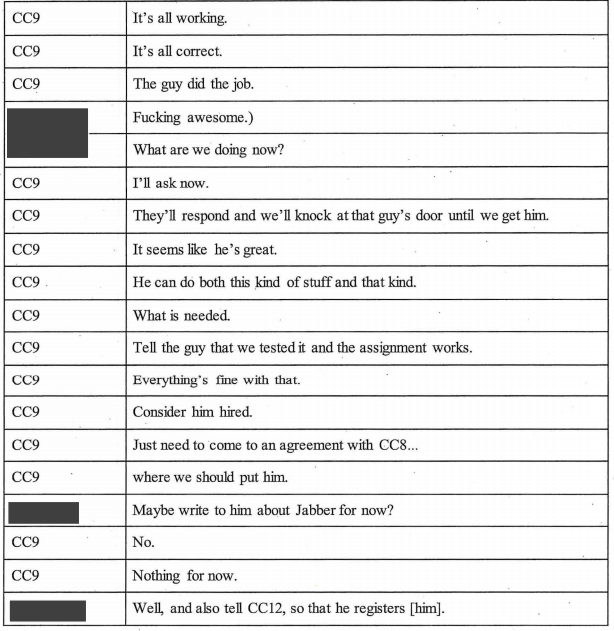

The following conversation, on or about June 1, 2016, concerned a potential new Trickbot hire who successfully completed a test task that involved altering a Firefox Web browser.

Other conversation snippets in the indictment suggest the majority of new recruits understand that what the projects and test tasks they are being asked to perform are related to cybercrime activity.

“The majority understand that this is blackhat and asking for the commercial target,” wrote the defendant identified only as Co-Conspirator 8 (CC8).

But what about new hires that aren’t hip to exactly how the programs they’re being asked to create get used? Another source in the threat intelligence industry who has had access to the inner workings of Trickbot provided some additional context on how developers are onboarded into the group.

“There’s a two-step hiring process where at first you may not understand who you’re working for,” said the source. “But that timeframe is typically pretty short, like less than a year.”

After that, if the candidate is talented and industrious enough, someone in the Trickbot group will “read in” the new recruit — i.e. explain in plain terms how their work is being used.

“If you’re good, at some point they’re going to read you in and you’ll know, but if you’re not good or you’re not okay with that, they will triage that pretty quickly and your services will no longer be required,” the source said. “But if you make it past that first year, the chances that you still don’t know what you’re doing are very slim.”

According to the DOJ, Witte had access to Trickbot for roughly two years between 2018 and 2020.

Investigators say prior to launching Trickbot, some members of the conspiracy previously were responsible for disseminating Dyre, a particularly stealthy password stealer that looked for passwords used at various banks. The government says Trickbot members — including Witte — routinely used bank account passwords stolen by their malware to drain victim bank accounts and send the money to networks of money mules.

The hiring model adopted by Trickbot allows the gang to recruit a steady stream of talented developers cheaply and covertly. But it also introduces the very real risk that new recruits may offer investigators a way to infiltrate the group’s operations, and possibly even identify co-conspirators.

Ransomware attacks are nearly all perpetrated these days by ransomware affiliate groups which constantly recruit new members to account for attrition, competition from other ransomware groups, and for the odd affiliate who gets busted by law enforcement.

Under the ransomware affiliate model, a cybercriminal can earn up to 85 percent of the total ransom paid by a victim company he or she is responsible for compromising and bringing to the group. But from time to time, poor operational security by an affiliate exposes the gang’s entire operation.

On June 7, the DOJ announced it had clawed back $2.3 million worth of Bitcoin that Colonial Pipeline paid to ransomware extortionists last month. The funds had been sent to DarkSide, a ransomware-as-a-service syndicate that disbanded after a May 14 farewell message to affiliates saying its Internet servers and cryptocurrency stash were seized by unknown law enforcement entities.

“The proceeds of the victim’s ransom payment…had been transferred to a specific address, for which the FBI has the ‘private key,’ or the rough equivalent of a password needed to access assets accessible from the specific Bitcoin address,” the DOJ explained, somewhat cryptically.

Multiple security experts quickly zeroed in on how investigators were able to retrieve the funds, which did not represent the total amount Colonial paid (~$4.4 million): The amount seized was roughly what a top DarkSide affiliate would have earned for scoring the initial malware infection that precipitated the ransomware incident.