Fighting Fake EDRs With ‘Credit Ratings’ for Police

mercredi 27 avril 2022 à 16:27When KrebsOnSecurity recently explored how cybercriminals were using hacked email accounts at police departments worldwide to obtain warrantless Emergency Data Requests (EDRs) from social media firms and technology providers, many security experts called it a fundamentally unfixable problem. But don’t tell that to Matt Donahue, a former FBI agent who recently quit the agency to launch a startup that aims to help tech companies do a better job screening out phony law enforcement data requests — in part by assigning trustworthiness or “credit ratings” to law enforcement authorities worldwide.

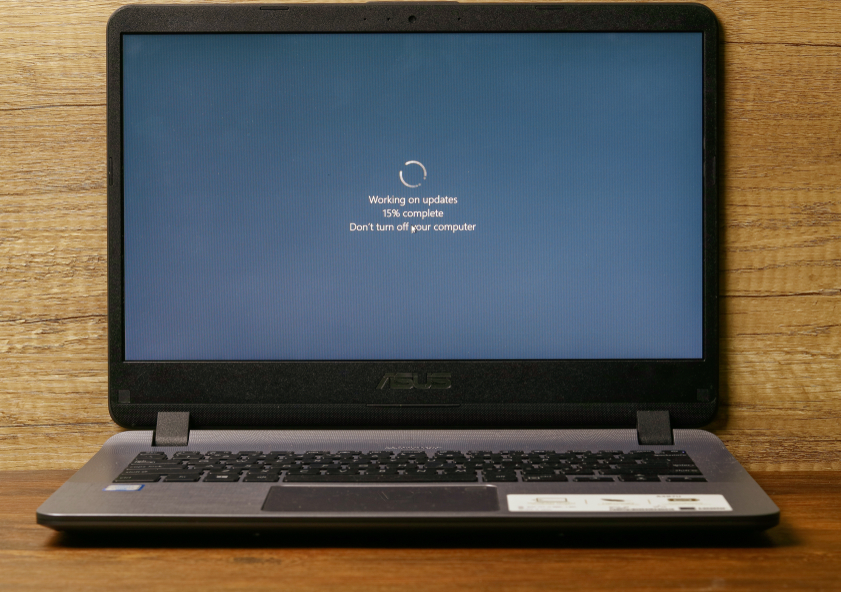

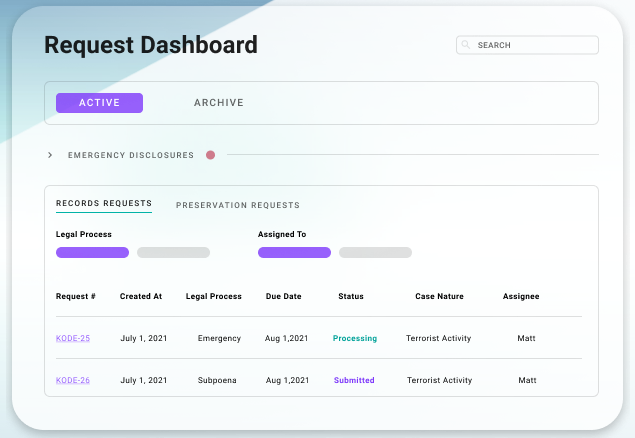

A sample Kodex dashboard. Image: Kodex.us.

Donahue is co-founder of Kodex, a company formed in February 2021 that builds security portals designed to help tech companies “manage information requests from government agencies who contact them, and to securely transfer data & collaborate against abuses on their platform.”

The 30-year-old Donahue said he left the FBI in April 2020 to start Kodex because it was clear that social media and technology companies needed help validating the increasingly large number of law enforcement requests domestically and internationally.

“So much of this is such an antiquated, manual process,” Donahue said of his perspective gained at the FBI. “In a lot of cases we’re still sending faxes when more secure and expedient technologies exist.”

Donahue said when he brought the subject up with his superiors at the FBI, they would kind of shrug it off, as if to say, “This is how it’s done and there’s no changing it.”

“My bosses told me I was committing career suicide doing this, but I genuinely believe fixing this process will do more for national security than a 20-year career at the FBI,” he said. “This is such a bigger problem than people give it credit for, and that’s why I left the bureau to start this company.”

One of the stated goals of Kodex is to build a scoring or reputation system for law enforcement personnel who make these data requests. After all, there are tens of thousands of police jurisdictions around the world — including roughly 18,000 in the United States alone — and all it takes for hackers to abuse the EDR process is illicit access to a single police email account.

Kodex is trying to tackle the problem of fake EDRs by working directly with the data providers to pool information about police or government officials submitting these requests, and hopefully making it easier for all customers to spot an unauthorized EDR.

Kodex’s first big client was cryptocurrency giant Coinbase, which confirmed their partnership but otherwise declined to comment for this story. Twilio confirmed it uses Kodex’s technology for law enforcement requests destined for any of its business units, but likewise declined to comment further.

Within their own separate Kodex portals, Twilio can’t see requests submitted to Coinbase, or vice versa. But each can see if a law enforcement entity or individual tied to one of their own requests has ever submitted a request to a different Kodex client, and then drill down further into other data about the submitter, such as Internet address(es) used, and the age of the requestor’s email address.

Donahue said in Kodex’s system, each law enforcement entity is assigned a credit rating, wherein officials who have a long history of sending valid legal requests will have a higher rating than someone sending an EDR for the first time.

“In those cases, we warn the customer with a flash on the request when it pops up that we’re allowing this to come through because the email was verified [as being sent from a valid police or government domain name], but we’re trying to verify the emergency situation for you, and we will change that rating once we get new information about the emergency,” Donahue said.

“This way, even if one customer gets a fake request, we’re able to prevent it from happening to someone else,” he continued. “In a lot of cases with fake EDRs, you can see the same email [address] being used to message different companies for data. And that’s the problem: So many companies are operating in their own silos and are not able to share information about what they’re seeing, which is why we’re seeing scammers exploit this good faith process of EDRs.”

NEEDLES IN THE HAYSTACK

As social media and technology platforms have grown over the years, so have the volumes of requests from law enforcement agencies worldwide for user data. For example, in its latest transparency report mobile giant Verizon reported receiving 114,000 data requests of all types from U.S. law enforcement entities in the second half of 2021.

Verizon said approximately 35,000 of those requests (~30 percent) were EDRs, and that it provided data in roughly 91 percent of those cases. The company doesn’t disclose how many EDRs came from foreign law enforcement entities during that same time period. Verizon currently asks law enforcement officials to send these requests via fax.

Validating legal requests by domain name may be fine for data demands that include documents like subpoenas and search warrants, which can be validated with the courts. But not so for EDRs, which largely bypass any official review and do not require the requestor to submit any court-approved documents.

Police and government authorities can legitimately request EDRs to learn the whereabouts or identities of people who have posted online about plans to harm themselves or others, or in other exigent circumstances such as a child abduction or abuse, or a potential terrorist attack.

But as KrebsOnSecurity reported in March, it is now clear that crooks have figured out there is no quick and easy way for a company that receives one of these EDRs to know whether it is legitimate. Using illicit access to hacked police email accounts, the attackers will send a fake EDR along with an attestation that innocent people will likely suffer greatly or die unless the requested data is provided immediately.

In this scenario, the receiving company finds itself caught between two unsavory outcomes: Failing to immediately comply with an EDR — and potentially having someone’s blood on their hands — or possibly leaking a customer record to the wrong person. That might explain why the compliance rate for EDRs is usually quite high — often upwards of 90 percent.

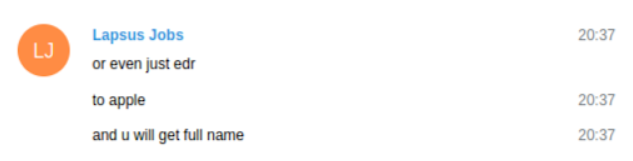

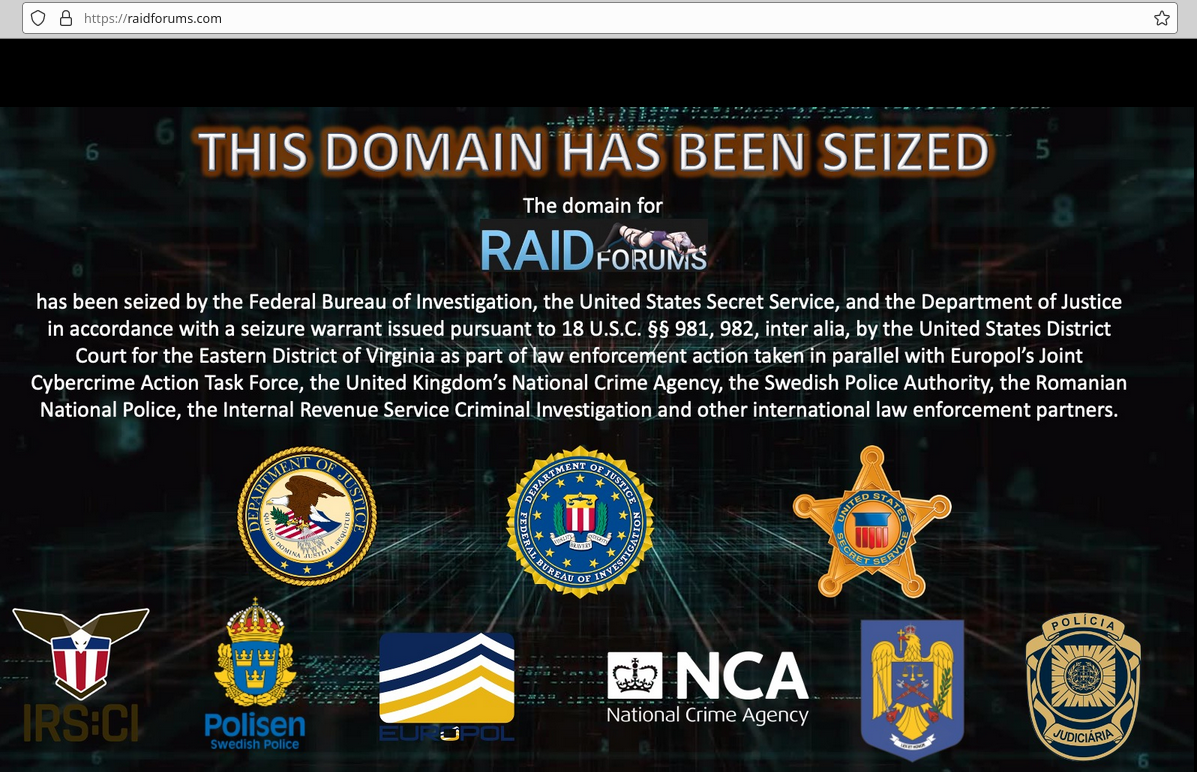

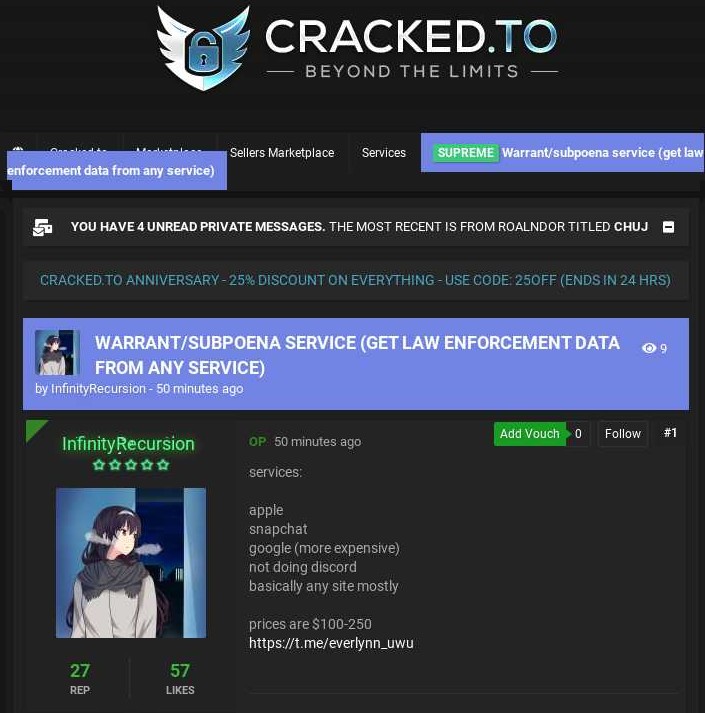

Fake EDRs have become such a reliable method in the cybercrime underground for obtaining information about account holders that several cybercriminals have started offering services that will submit these fraudulent EDRs on behalf of paying clients to a number of top social media and technology firms.

A fake EDR service advertised on a hacker forum in 2021.

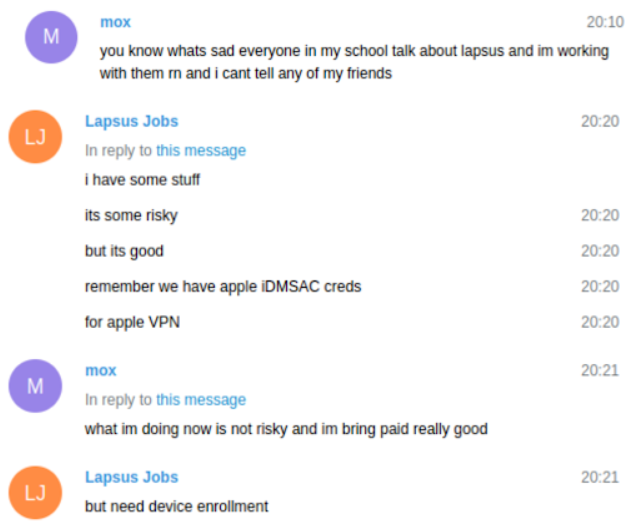

An individual who’s part of the community of crooks that are abusing fake EDR told KrebsOnSecurity the schemes often involve hacking into police department emails by first compromising the agency’s website. From there, they can drop a backdoor “shell” on the server to secure permanent access, and then create new email accounts within the hacked organization.

In other cases, hackers will try to guess the passwords of police department email systems. In these attacks, the hackers will identify email addresses associated with law enforcement personnel, and then attempt to authenticate using passwords those individuals have used at other websites that have been breached previously.

EDR OVERLOAD?

Donahue said depending on the industry, EDRs make up between 5 percent and 30 percent of the total volume of requests. In contrast, he said, EDRs amount to less than three percent of the requests sent through Kodex portals used by customers.

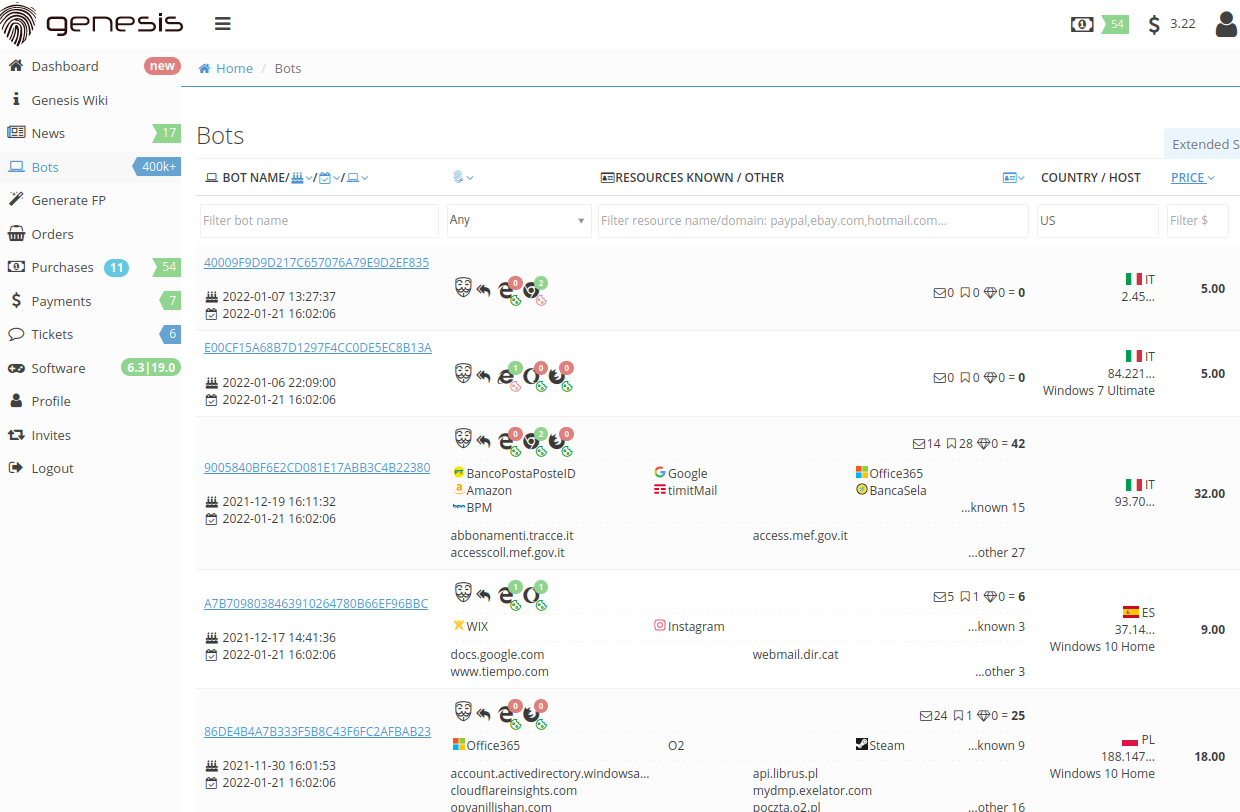

KrebsOnSecurity sought to verify those numbers by compiling EDR statistics based on annual or semi-annual transparency reports from some of the largest technology and social media firms. While there are no available figures on the number of fake EDRs each provider is receiving each year, those phony requests can easily hide amid an increasingly heavy torrent of legitimate demands.

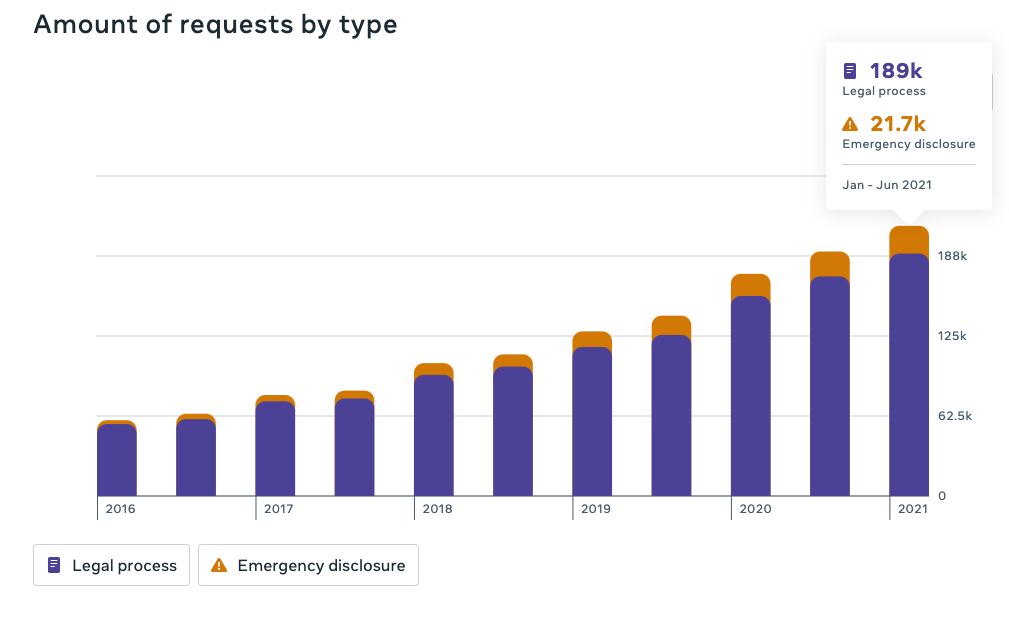

Meta/Facebook says roughly 11 percent of all law enforcement data requests — 21,700 of them — were EDRs in the first half of 2021. Almost 80 percent of the time the company produced at least some data in response. Facebook has long used its own online portal where law enforcement officials must first register before submitting requests.

Government data requests, including EDRs, received by Facebook over the years. Image: Meta Transparency Report.

Apple said it received 1,162 emergency requests for data in the last reporting period it made public — July – December 2020. Apple’s compliance with EDRs was 93 percent worldwide in 2020. Apple’s website says it accepts EDRs via email, after applicants have filled out a supplied PDF form. [As a lifelong Apple user and customer, I was floored to learn that the richest company in the world — which for several years has banked heavily on privacy and security promises to customers — still relies on email for such sensitive requests].

Twitter says it received 1,860 EDRs in the first half of 2021, or roughly 15 percent of the global information requests sent to Twitter. Twitter accepts EDRs via an interactive form on the company’s website. Twitter reports that EDRs decreased by 25% during this reporting period, while the aggregate number of accounts specified in these requests decreased by 15%. The United States submitted the highest volume of global emergency requests (36%), followed by Japan (19%), and India (12%).

Discord reported receiving 378 requests for emergency data disclosure in the first half of 2021. Discord accepts EDRs via a specified email address.

For the six months ending in December 2021, Snapchat said it received 2,085 EDRs from authorities in the United States (with a 59 percent compliance rate), and another 1,448 from international police (64 percent granted). Snapchat has a form for submitting EDRs on its website.

TikTok‘s resources on government data requests currently lead to a “Page not found” error, but a company spokesperson said TikTok received 715 EDRs in the first half of 2021. That’s up from 409 EDRs in the previous six months. Tiktok handles EDRs via a form on its website.

The current transparency reports for both Google and Microsoft do not break out EDRs by category. Microsoft says that in the second half of 2021 it received more than 25,000 government requests, and that it complied at least partly with those requests more than 90 percent of the time.

Microsoft runs its own portal that law enforcement officials must register at to submit legal requests, but that portal doesn’t accept requests for other Microsoft properties, such as LinkedIn or Github.

Google said it received more than 113,000 government requests for user data in the last half of 2020, and that about 76 percent of the requests resulted in the disclosure of some user information. Google doesn’t publish EDR numbers, and it did not respond to requests for those figures. Google also runs its own portal for accepting law enforcement data requests.

Verizon reports (PDF) receiving more than 35,000 EDRs from just U.S. law enforcement in the second half of 2021, out of a total of 114,000 law enforcement requests (Verizon doesn’t disclose how many EDRs came from foreign law enforcement entities). Verizon said it complied with approximately 91 percent of requests. The company accepts law enforcement requests via snail mail or fax.

Image: Verizon.com.

AT&T says (PDF) it received nearly 19,000 EDRs in the second half of 2021; it provided some data roughly 95 percent of the time. AT&T requires EDRs to be faxed.

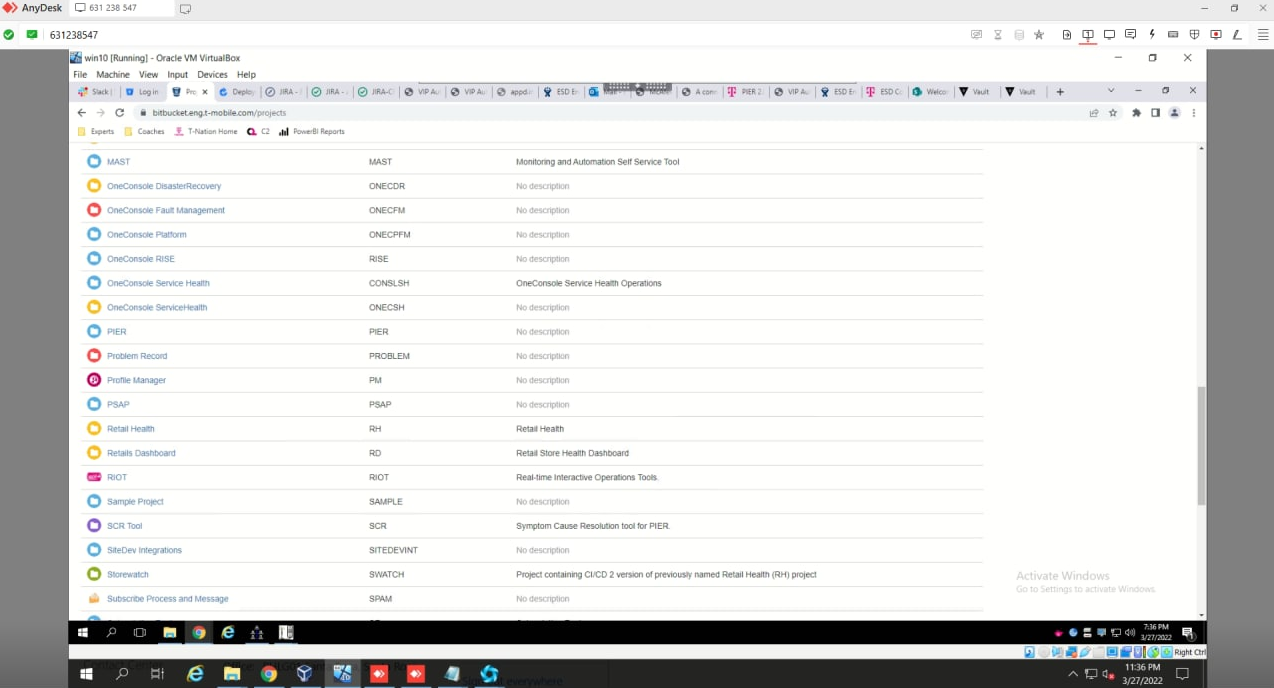

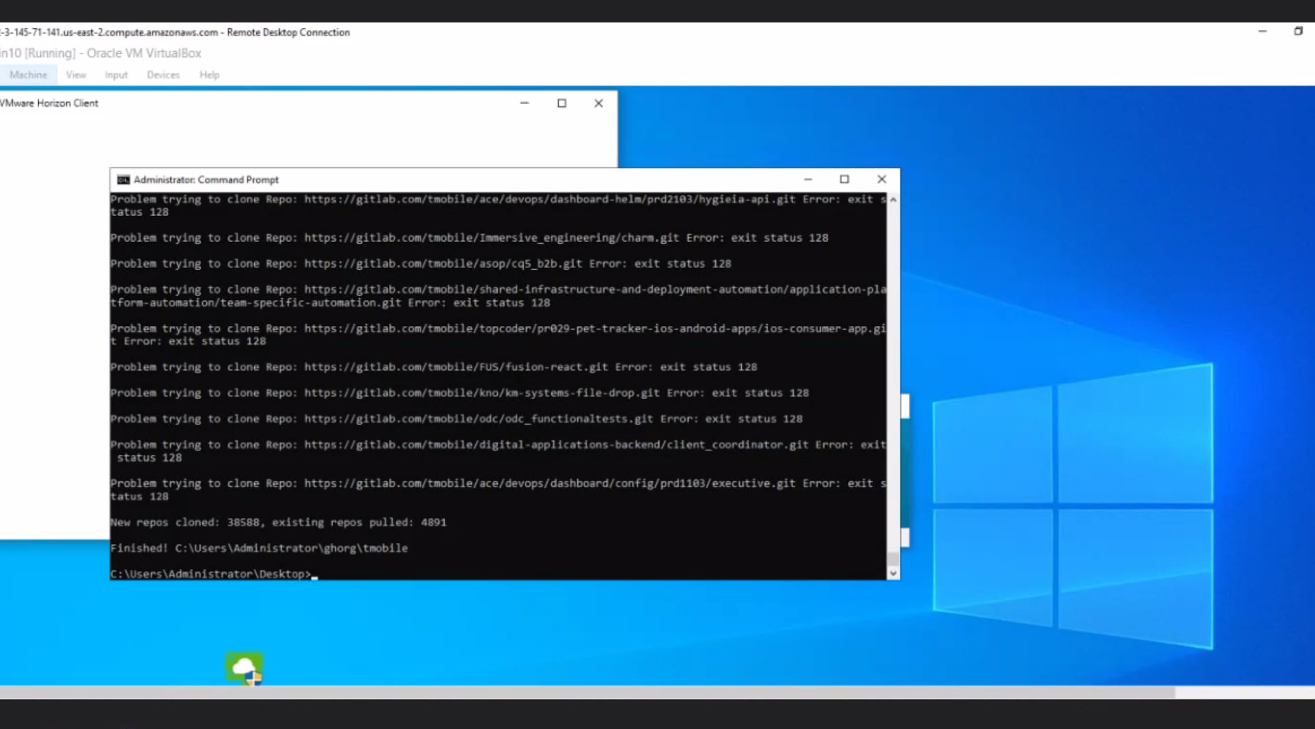

The most recent transparency report published by T-Mobile says the company received more than 164,000 “emergency/911” requests in 2020 — but it does not specifically call out EDRs. Like its old school telco brethren, T-Mobile requires EDRs to be faxed. T-Mobile did not respond to requests for more information.

Data from T-Mobile’s most recent transparency report in 2020. Image: T-Mobile.

These so-called Mobile Device Management (MDM) systems retrieve information about the underlying hardware and software powering the system requesting access, and then relay that information along with any login credentials.

These so-called Mobile Device Management (MDM) systems retrieve information about the underlying hardware and software powering the system requesting access, and then relay that information along with any login credentials.