It’s Way Too Easy to Get a .gov Domain Name

mercredi 27 novembre 2019 à 03:08Many readers probably believe they can trust links and emails coming from U.S. federal government domain names, or else assume there are at least more stringent verification requirements involved in obtaining a .gov domain versus a commercial one ending in .com or .org. But a recent experience suggests this trust may be severely misplaced, and that it is relatively straightforward for anyone to obtain their very own .gov domain.

Earlier this month, KrebsOnSecurity received an email from a researcher who said he got a .gov domain simply by filling out and emailing an online form, grabbing some letterhead off the homepage of a small U.S. town that only has a “.us” domain name, and impersonating the town’s mayor in the application.

“I used a fake Google Voice number and fake Gmail address,” said the source, who asked to remain anonymous for this story but who said he did it mainly as a thought experiment. “The only thing that was real was the mayor’s name.”

The email from this source was sent from exeterri[.]gov, a domain registered on Nov. 14 that at the time displayed the same content as the .us domain it was impersonating — town.exeter.ri.us — which belongs to the town of Exeter, Rhode Island (the impostor domain is no longer resolving).

“I had to [fill out] ‘an official authorization form,’ which basically just lists your admin, tech guy, and billing guy,” the source continued. “Also, it needs to be printed on ‘official letterhead,’ which of course can be easily forged just by Googling a document from said municipality. Then you either mail or fax it in. After that, they send account creation links to all the contacts.”

Technically, what my source did was wire fraud (obtaining something of value via the Internet/telephone/fax through false pretenses); had he done it through the U.S. mail, he could be facing mail fraud charges if caught.

But a cybercriminal — particularly a state-sponsored actor operating outside the United States — likely would not hesitate to do so if he thought the $400 pricetag for registering a .gov was worth it to make his malicious website, emails or fake news social media campaign more believable.

“I never said it was legal, just that it was easy,” the source said. “I assumed there would be at least ID verification. The deepest research I needed to do was Yellow Pages records.”

On Tuesday, KrebsOnSecurity contacted officials in the real town of Exeter, RI to find out if anyone from the U.S. General Services Administration — the federal agency responsible for managing the .gov domain registration process — had sought to validate the request prior to granting a .gov in their name.

A person who called back from the town clerk’s office but who asked not to be named said someone from the GSA did phone the mayor’s office on Nov. 24 — which was four days after I reached out to the federal agency about the domain in question and approximately 10 days after the GSA had already granted the phony request.

WHO WANTS TO BE A GOVERNMENT?

Responding today via email, a GSA spokesperson said the agency doesn’t comment on open investigations.

“GSA is working with the appropriate authorities and has already implemented additional fraud prevention controls,” the agency wrote, without elaborating on what those additional controls might be.

KrebsOnSecurity did get a substantive response from the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, a division of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security which is leading efforts to protect the federal .gov domain of civilian government networks [NB: The head of CISA, Christopher C. Krebs, is of no relation to this author].

The CISA said this matter is so critical to maintaining the security and integrity of the .gov space that DHS is now making a play to assume control over the issuance of all .gov domains.

“The .gov top-level domain (TLD) is critical infrastructure for thousands of federal, state and local government organizations across the country,” reads a statement CISA sent to KrebsOnSecurity. “Its use by these institutions should instill trust. In order to increase the security of all US-based government organizations, CISA is seeking the authority to manage the .gov TLD and assume governance from the General Services Administration.”

The statement continues:

“This transfer would allow CISA to modernize the .gov registrar, enhance the security of individual .gov domains, ensure that only authorized users obtain a .gov domain, proactively validate existing .gov holders, and better secure everyone that relies on .gov. We are appreciative of Congress’ efforts to put forth the DOTGOV bill [link added] that would grant CISA this important authority moving forward. GSA has been an important partner in these efforts and our two agencies will continue to work hand-in-hand to identify and implement near-term security enhancements to the .gov.”

FEELING LUCKY? LASVEGAS.GOV CAN BE YOURS FOR $400!

In an era when the nation’s top intelligence agencies continue to warn about ongoing efforts by Russia and other countries to interfere in our elections and democratic processes, it may be difficult to fathom that an attacker could so easily leverage such a simple method for impersonating state and local authorities.

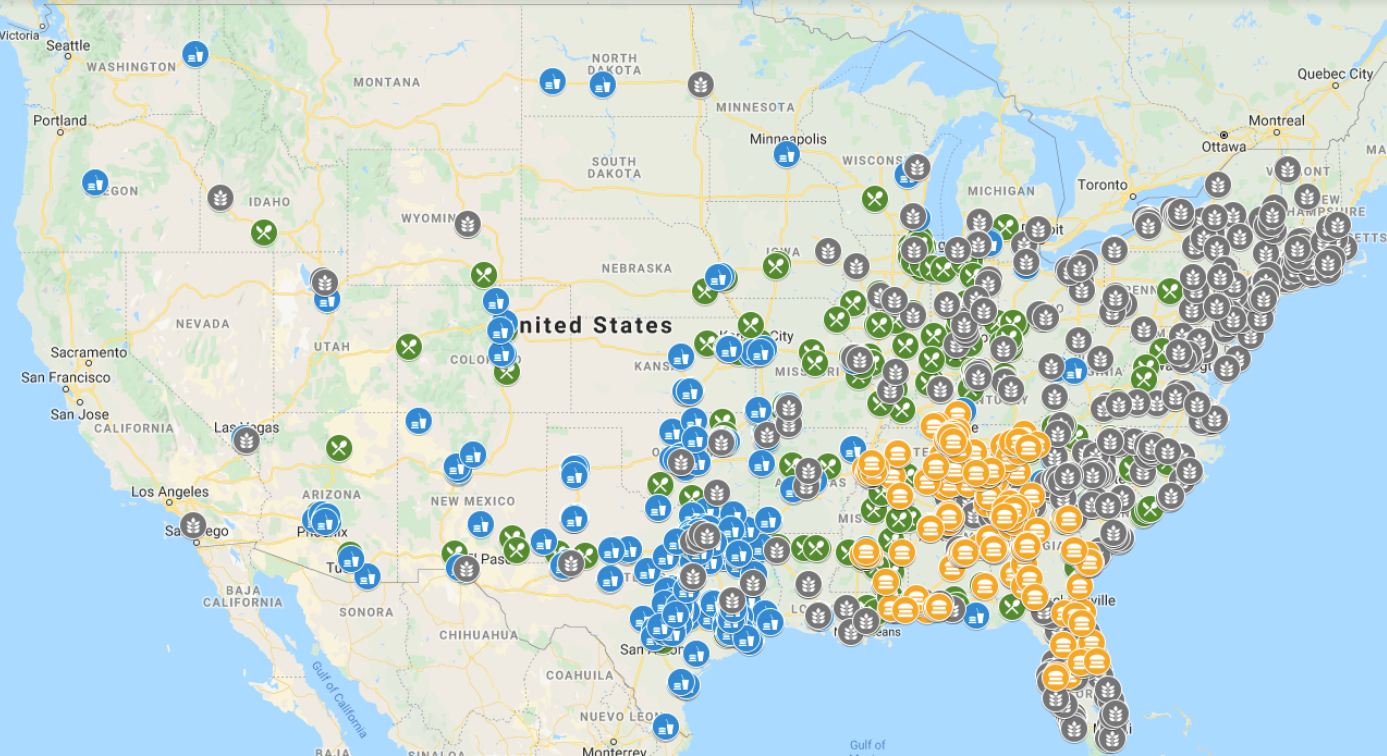

Despite the ease with which apparently anyone can get their own .gov domain, there are plenty of major U.S. cities that currently do not have one, probably because they never realized they could with very little effort or expense. A review of the Top 10 most populous U.S. cities indicates only half of them have obtained .gov domains, including Chicago, Dallas, Phoenix, San Antonio, and San Diego.

Yes, you read that right: houston.gov, losangeles.gov, newyorkcity.gov, and philadelphia.gov are all still available. As is the .gov for San Jose, Calif., the economic, cultural and political center of Silicon Valley. No doubt a great number of smaller cities also haven’t figured out they’re eligible to secure their own .gov domains.

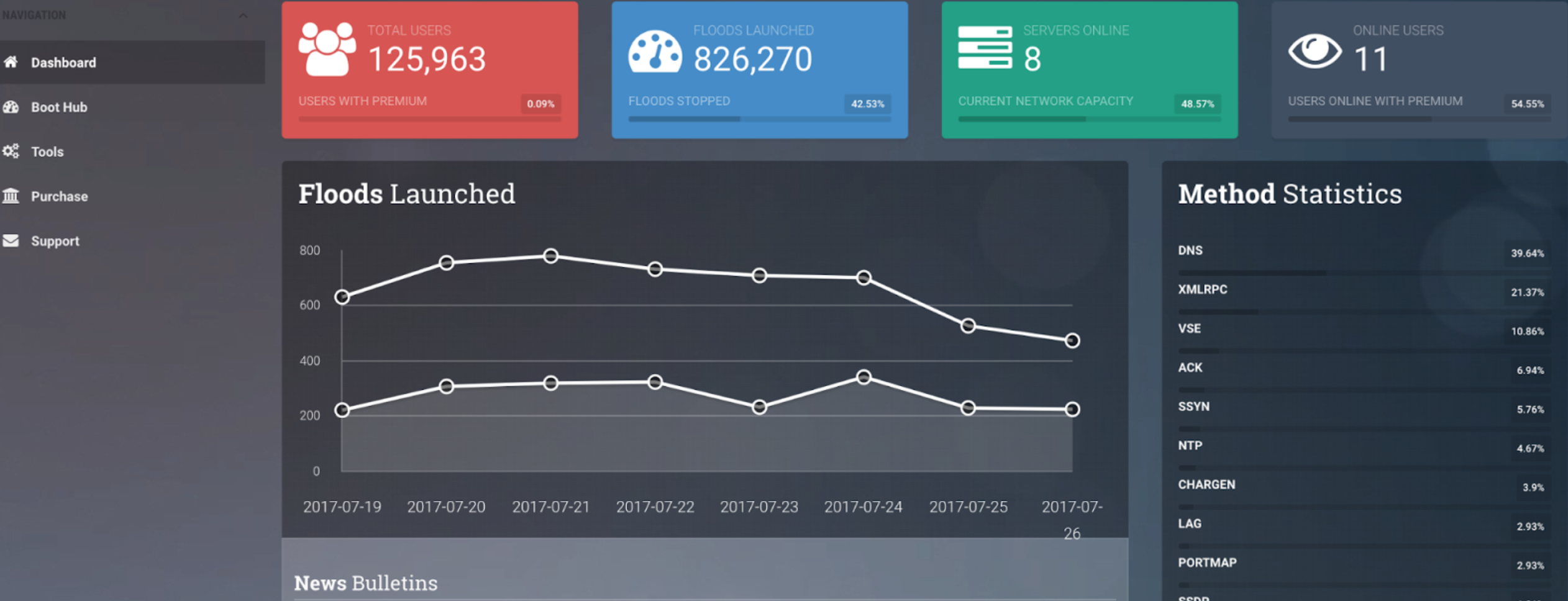

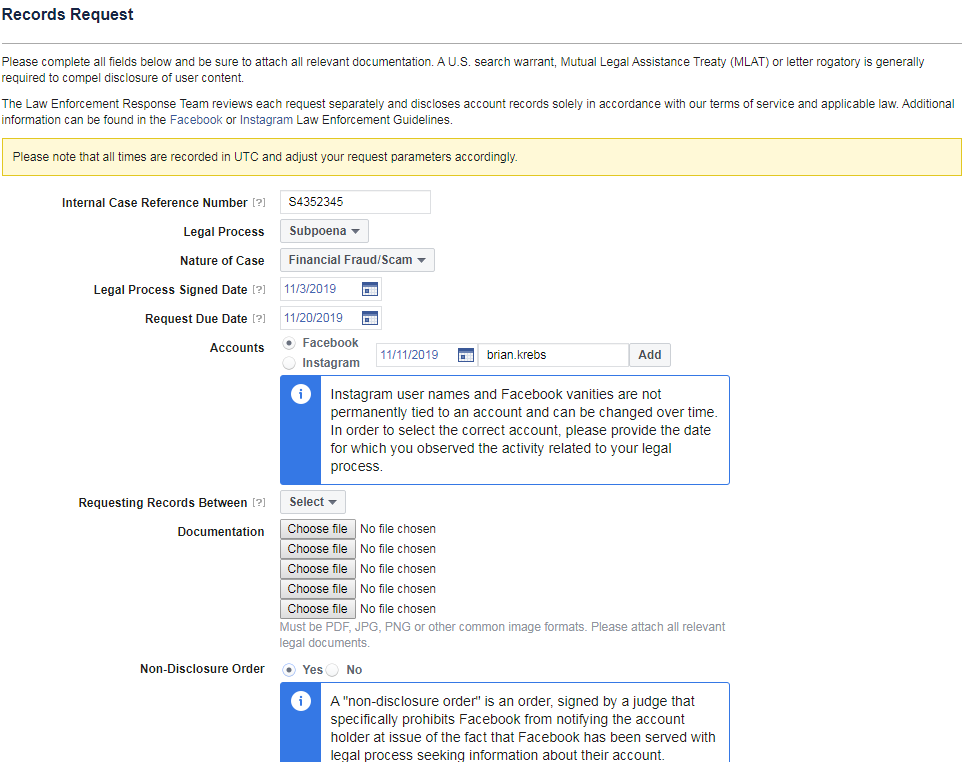

In addition to being able to convincingly spoof communications from and websites for cities and towns, there are almost certainly a myriad other ways that possessing a phony .gov domain could be abused. For example, my source said he was able to register his domain in Facebook’s law enforcement subpoena system, although he says he did not attempt to abuse that access.

The source who successfully registered an impostor .gov domain said he was able to use that access to register for Facebook’s law enforcement subpoena system.

One way fraudsters might make a fake .gov domain even more convincing would be to equip the site with an SSL certificate so that the phony domain displays the green padlock icon in a user’s Web browser. While the presence of a lock icon is most definitely not an indicator that a site is legitimate (somewhere north of 50 percent of all phishing sites now include the padlock), anyone who obtains a .gov domain is automatically eligible to have an SSL cert issued for that domain by the GSA.

Now consider what a well-funded adversary could do on Election Day armed with a handful of .gov domains for some major cities in Democrat strongholds within key swing states: The attackers register their domains a few days in advance of the election, and then on Election Day send out emails signed by .gov from, say, miami.gov (also still available) informing residents that bombs had gone off at polling stations in Democrat-leaning districts. Such a hoax could well decide the fate of a close national election.

John Levine, a domain name expert, consultant and author of the book The Internet for Dummies, said the .gov domain space wasn’t always so open as it is today.

“Back in the day, everyone not in the federal government was supposed to register in the .us space,” Levine said. “At some point, someone decided .gov is going to be more democratic and let everyone in the states register. But as we see, there’s still no validation.”

Levine, who served three years as mayor of the village of Trumansburg, New York, said it would not be terribly difficult for the GSA to do a better job of validating .gov domain requests, but that some manual verification would probably be required.

“When I was a mayor, I was in frequent contact with the state, and states know who all their municipalities are and how to reach people in charge of them,” Levine said. “Also, every state has a Secretary of State that keeps track of what all the subdivisions are, and including them in the process could help as well.”

Levine said like the Internet itself, this entire debacle is yet another example of an important resource with potentially explosive geopolitical implications that was never designed with security or authentication in mind.

“It turns out that the GSA is pretty good at doing boring clerical stuff,” he said. “But as we keep discovering, what we once thought was a boring clerical thing now actually has real-world security implications.”