Dangerous Domain Corp.com Goes Up for Sale

samedi 8 février 2020 à 18:32As an early domain name investor, Mike O’Connor had by 1994 snatched up several choice online destinations, including bar.com, cafes.com, grill.com, place.com, pub.com and television.com. Some he sold over the years, but for the past 26 years O’Connor refused to auction perhaps the most sensitive domain in his stable — corp.com. It is sensitive because years of testing shows whoever wields it would have access to an unending stream of passwords, email and other proprietary data belonging to hundreds of thousands of systems at major companies around the globe.

Now, facing 70 and seeking to simplify his estate, O’Connor is finally selling corp.com. The asking price — $1.7 million — is hardly outlandish for a 4-letter domain with such strong commercial appeal. O’Connor said he hopes Microsoft Corp. will buy it, but fears they won’t and instead it will get snatched up by someone working with organized cybercriminals or state-funded hacking groups bent on undermining the interests of Western corporations.

One reason O’Connor hopes Microsoft will buy it is that by virtue of the unique way that Windows handles resolving domain names on a local network, virtually all of the computers trying to share sensitive data with corp.com are somewhat confused Windows PCs. More importantly, early versions of Windows actually encouraged the adoption of insecure settings that made it more likely Windows computers might try to share sensitive data with corp.com.

At issue is a problem known as “namespace collision,” a situation where domain names intended to be used exclusively on an internal company network end up overlapping with domains that can resolve normally on the open Internet.

Windows computers on an internal corporate network validate other things on that network using a Microsoft innovation called Active Directory, which is the umbrella term for a broad range of identity-related services in Windows environments. A core part of the way these things find each other involves a Windows feature called “DNS name devolution,” which is a kind of network shorthand that makes it easier to find other computers or servers without having to specify a full, legitimate domain name for those resources.

For instance, if a company runs an internal network with the name internalnetwork.example.com, and an employee on that network wishes to access a shared drive called “drive1,” there’s no need to type “drive1.internalnetwork.example.com” into Windows Explorer; typing “\\drive1\” alone will suffice, and Windows takes care of the rest.

But things can get far trickier with an internal Windows domain that does not map back to a second-level domain the organization actually owns and controls. And unfortunately, in early versions of Windows that supported Active Directory — Windows 2000 Server, for example — the default or example Active Directory path was given as “corp,” and many companies apparently adopted this setting without modifying it to include a domain they controlled.

Compounding things further, some companies then went on to build (and/or assimilate) vast networks of networks on top of this erroneous setting.

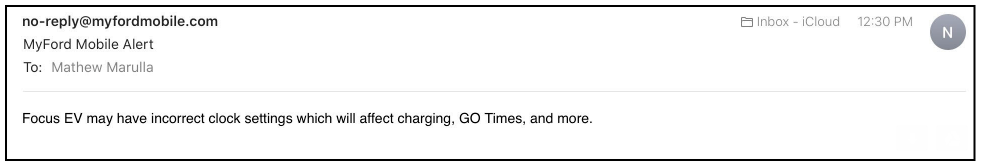

Now, none of this was much of a security concern back in the day when it was impractical for employees to lug their bulky desktop computers and monitors outside of the corporate network. But what happens when an employee working at a company with an Active Directory network path called “corp” takes a company laptop to the local Starbucks?

Chances are good that at least some resources on the employee’s laptop will still try to access that internal “corp” domain. And because of the way DNS name devolution works on Windows, that company laptop online via the Starbucks wireless connection is likely to then seek those same resources at “corp.com.”

In practical terms, this means that whoever controls corp.com can passively intercept private communications from hundreds of thousands of computers that end up being taken outside of a corporate environment which uses this “corp” designation for its Active Directory domain.

INSTANT CORPORATE BOTNET, ANYONE?

That’s according to Jeff Schmidt, a security expert who conducted a lengthy study on DNS namespace collisions funded in part by grants from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. As part of that analysis, Schmidt convinced O’Connor to hold off selling corp.com so he and others could better understand and document the volume and types of traffic flowing to it each day.

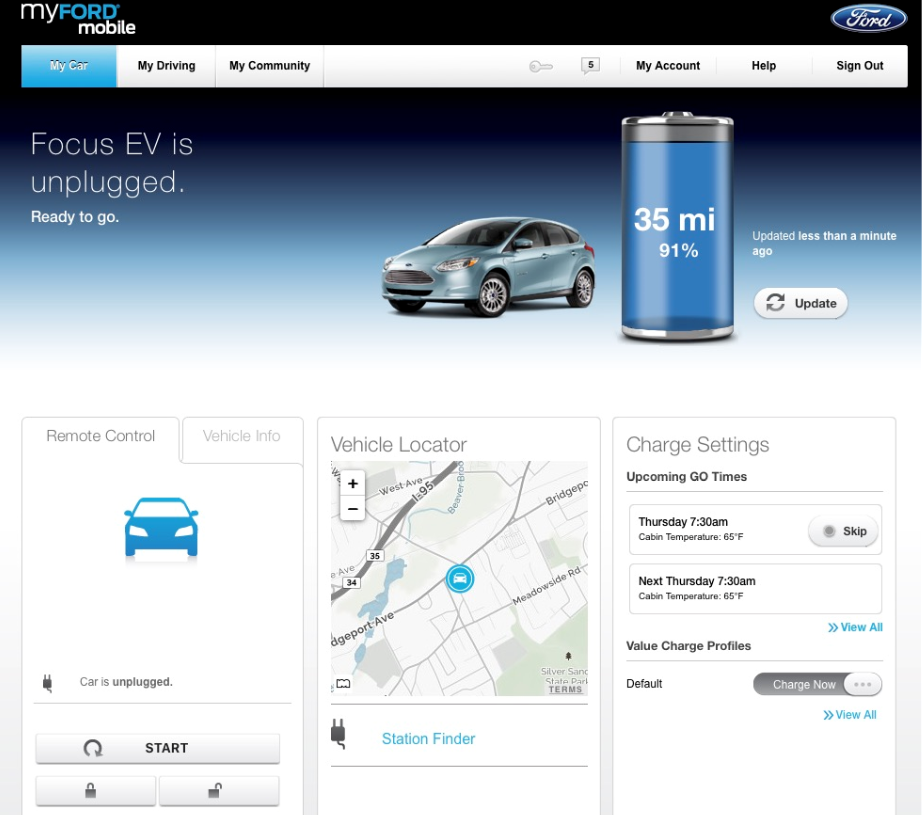

During an eight month analysis of wayward internal corporate traffic destined for corp.com in 2019, Schmidt found more than 375,000 Windows PCs were trying to send this domain information it had no business receiving — including attempts to log in to internal corporate networks and access specific file shares on those networks.

For a brief period during that testing, Schmidt’s company JAS Global Advisors accepted connections at corp.com that mimicked the way local Windows networks handle logins and file-sharing attempts.

“It was terrifying,” Schmidt said. “We discontinued the experiment after 15 minutes and destroyed the data. A well-known offensive tester that consulted with JAS on this remarked that during the experiment it was ‘raining credentials’ and that he’d never seen anything like it.”

Likewise, JAS temporarily configured corp.com to accept incoming email.

“After about an hour we received in excess of 12 million emails and discontinued the experiment,” Schmidt said. “While the vast majority of the emails were of an automated nature, we found some of the emails to be sensitive and thus destroyed the entire corpus without further analysis.”

Schmidt said he and others concluded that whoever ends up controlling corp.com could have an instant botnet of well-connected enterprise machines.

“Hundreds of thousands of machines directly exploitable and countless more exploitable via lateral movement once in the enterprise,” he said. “Want an instant foothold into about 30 of the world’s largest companies according to the Forbes Global 2000? Control corp.com.”

THE EARLY ADVENTURES OF CORP.COM

Schmidt’s findings closely mirror what O’Connor discovered in the few years corp.com was live on the Internet after he initially registered it back in 1994. O’Connor said early versions of a now-defunct Web site building tool called Microsoft FrontPage suggested corporation.com (another domain registered early on by O’Connor) as an example domain in its setup wizard.

That experience, portions of which are still indexed by the indispensable Internet Archive, saw O’Connor briefly redirecting queries for the domain to the Web site of a local adult sex toy shop as a joke. He soon got angry emails from confused people who’d also CC’d Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates.

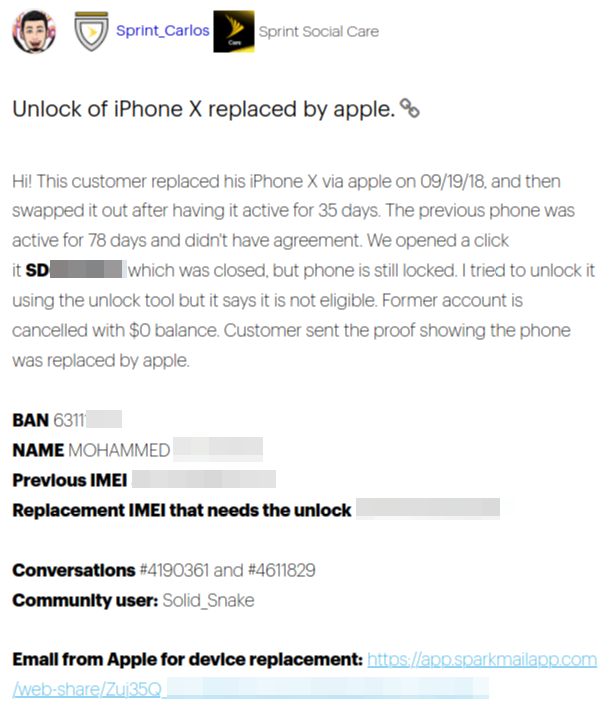

Archive.org’s index of corp.com from 1997, when its owner Mike O’Connor briefly enabled a Web site mainly to shame Microsoft for the default settings of its software.

O’Connor said he also briefly enabled an email server on corp.com, mainly out of morbid curiosity to see what would happen next.

“Right away I started getting sensitive emails, including pre-releases of corporate financial filings with The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, human resources reports and all kinds of scary things,” O’Connor recalled in an interview with KrebsOnSecurity. “For a while, I would try to correspond back to corporations that were making these mistakes, but most of them didn’t know what to do with that. So I finally just turned it off.”

TOXIC WASTE CLEANUP IS HARD

Microsoft declined to answer specific questions in response to Schmidt’s findings on the wayward corp.com traffic. But a spokesperson for the company shared a written statement acknowledging that “we sometimes reference ‘corp’ as a label in our naming documentation.”

“We recommend customers own second level domains to prevent being routed to the internet,” the statement reads, linking to this Microsoft Technet article on best practices for setting up domains in Active Directory.

Over the years, Microsoft has shipped several software updates to help decrease the likelihood of namespace collisions that could create a security problem for companies that still rely on Active Directory domains that do not map to a domain they control.

But both O’Connor and Schmidt say hardly any vulnerable organizations have deployed these fixes for two reasons. First, doing so requires the organization to take down its entire Active Directory network simultaneously for some period of time. Second, according to Microsoft applying the patch(es) will likely break or at least slow down a number of applications that the affected organization relies upon for day-to-day operations.

Faced with either or both of these scenarios, most affected companies probably decided the actual risk of not applying these updates was comparatively low, O’Connor said.

“The problem is that when you read the instructions for doing the repair, you realize that what they’re saying is, ‘Okay Megacorp, in order to apply this patch and for everything to work right, you have to take down all of your Active Directory services network-wide, and when you bring them back up after you applied the patch, a lot of your servers may not work properly’,” O’Connor said.

Curiously, Schmidt shared slides from a report submitted to a working group on namespace collisions suggesting that at least some of the queries corp.com received while he was monitoring it may have come from Microsoft’s own internal networks.

“The reason I believe this is Microsoft’s issue to solve is that someone that followed Microsoft’s recommendations when establishing an active directory several years back now has a problem,” Schmidt said.

“Even if all patches are applied and updated to Windows 10,” he continued. “And the problem will persist while there are active directories named ‘corp’ – which is forever. More practically, if corp.com falls into bad hands, the impact will be on Microsoft enterprise clients – and at large scale – paying, Microsoft clients they should protect.”

Asked why he didn’t just give corp.com to Microsoft as an altruistic gesture, O’Connor said the software giant ought to be accountable for its products and mistakes.

“It seems to me that Microsoft should stand up and shoulder the burden of the mistake they made,” he said. “But they’ve shown no real interest in doing that, and so I’ve shown no interest in giving it to them. I don’t really need the money. I’m basically auctioning off a chemical waste dump because I don’t want to pass it on to my kids and burden them with it. My frustration here is the good guys don’t care and the bad guys probably don’t know about it. But I expect the bad guys would like it.”

Further reading:

Mitigating the Risk of DNS Namespace Collisions (PDF)

DEFCON 21 – DNS May Be Hazardous to your Health (Robert Stucke)

Mitigating the Risk of Name Collision-Based Man-in-the-Middle Attacks (PDF)