Security Trade-Offs in the New EU Privacy Law

vendredi 27 avril 2018 à 19:27On two occasions this past year I’ve published stories here warning about the prospect that new European privacy regulations could result in more spams and scams ending up in your inbox. This post explains in a question and answer format some of the reasoning that went into that prediction, and responds to many of the criticisms leveled against it.

Before we get to the Q&A, a bit of background is in order. On May 25, 2018 the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) takes effect. The law, enacted by the European Parliament, requires companies to get affirmative consent for any personal information they collect on people within the European Union. Organizations that violate the GDPR could face fines of up to four percent of global annual revenues.

In response, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) — the nonprofit entity that manages the global domain name system — has proposed redacting key bits of personal data from WHOIS, the system for querying databases that store the registered users of domain names and blocks of Internet address ranges (IP addresses).

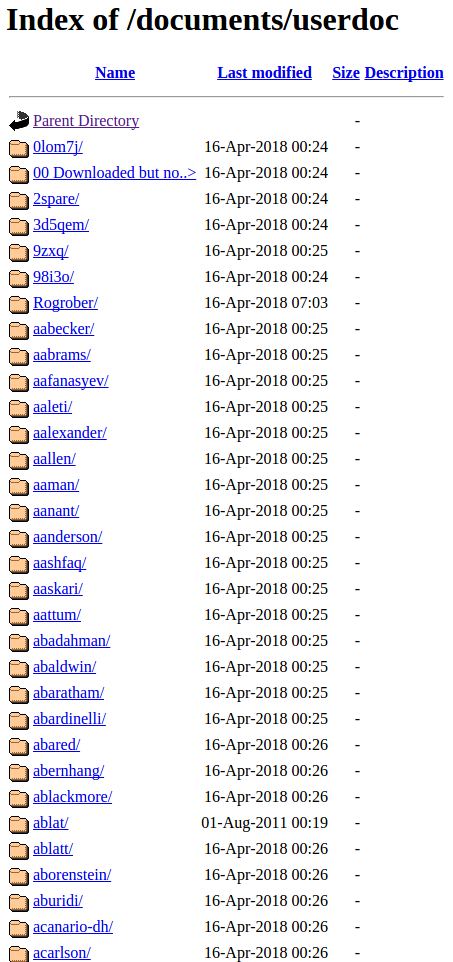

Under current ICANN rules, domain name registrars should collect and display a variety of data points when someone performs a WHOIS lookup on a given domain, such as the registrant’s name, address, email address and phone number. Most registrars offer a privacy protection service that shields this information from public WHOIS lookups; some registrars charge a nominal fee for this service, while others offer it for free.

But in a bid to help registrars comply with the GDPR, ICANN is moving forward on a plan to remove critical data elements from all public WHOIS records. Under the new system, registrars would collect all the same data points about their customers, yet limit how much of that information is made available via public WHOIS lookups.

The data to be redacted includes the name of the person who registered the domain, as well as their phone number, physical address and email address. The new rules would apply to all domain name registrars globally.

ICANN has proposed creating an “accreditation system” that would vet access to personal data in WHOIS records for several groups, including journalists, security researchers, and law enforcement officials, as well as intellectual property rights holders who routinely use WHOIS records to combat piracy and trademark abuse.

But at an ICANN meeting in San Juan, Puerto Rico last month, ICANN representatives conceded that a proposal for how such a vetting system might work probably would not be ready until December 2018. Assuming ICANN meets that deadline, it could be many months after that before the hundreds of domain registrars around the world take steps to adopt the new measures.

In a series of posts on Twitter, I predicted that the WHOIS changes coming with GDPR will likely result in a noticeable increase in cybercrime — particularly in the form of phishing and other types of spam. In response to those tweets, several authors on Wednesday published an article for Georgia Tech’s Internet Governance Project titled, “WHOIS afraid of the dark? Truth or illusion, let’s know the difference when it comes to WHOIS.”

The following Q&A is intended to address many of the more misleading claims and assertions made in that article.

Cyber criminals don’t use their real information in WHOIS registrations, so what’s the big deal if the data currently available in WHOIS records is no longer in the public domain after May 25?

I can point to dozens of stories printed here — and probably hundreds elsewhere — that clearly demonstrate otherwise. Whether or not cyber crooks do provide their real information is beside the point. ANY information they provide — and especially information that they re-use across multiple domains and cybercrime campaigns — is invaluable to both grouping cybercriminal operations and in ultimately identifying who’s responsible for these activities.

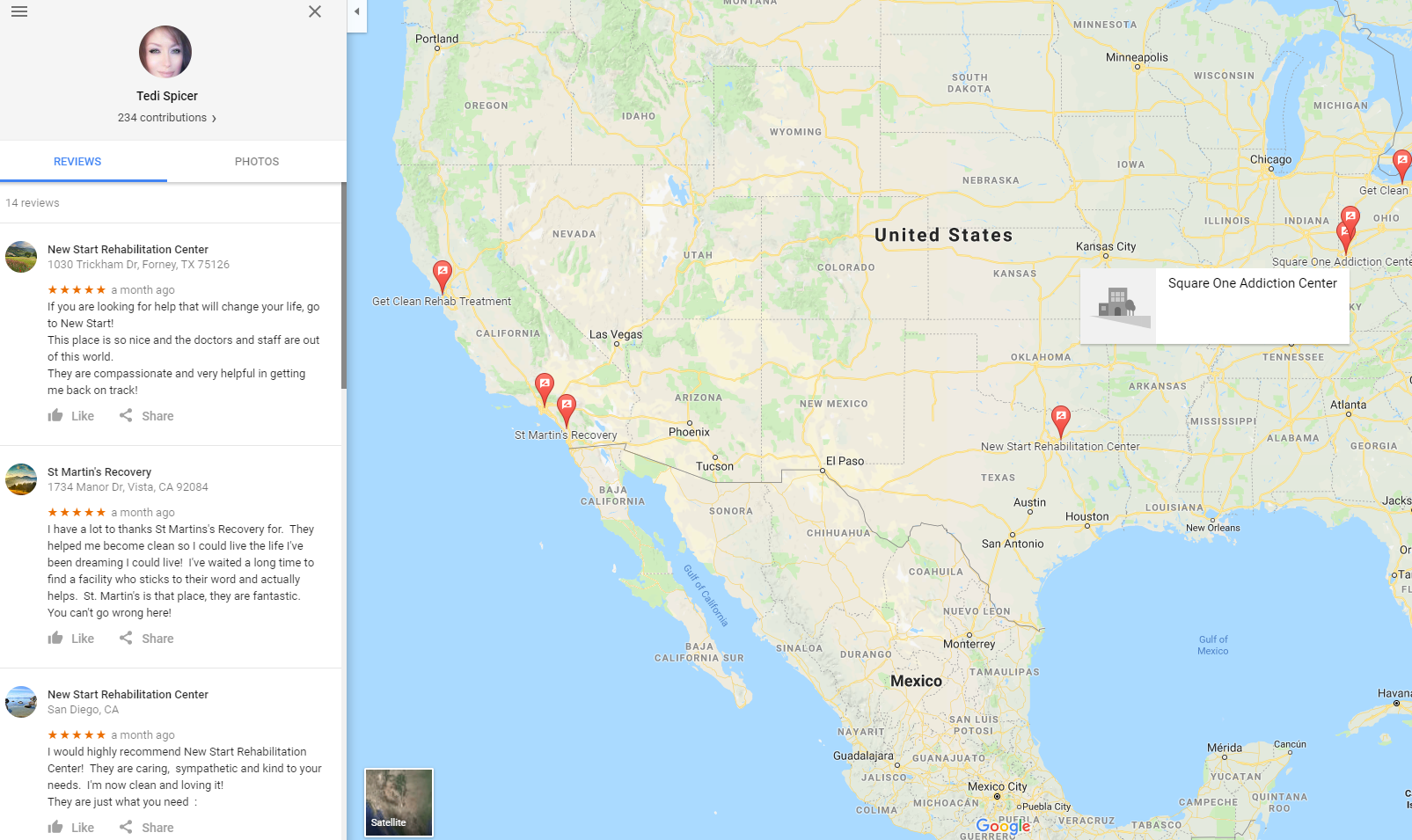

To understand why data reuse in WHOIS records is so common among crooks, put yourself in the shoes of your average scammer or spammer — someone who has to register dozens or even hundreds or thousands of domains a week to ply their trade. Are you going to create hundreds or thousands of email addresses and fabricate as many personal details to make your WHOIS listings that much harder for researchers to track? The answer is that those who take this extraordinary step are by far and away the exception rather than the rule. Most simply reuse the same email address and phony address/phone/contact information across many domains as long as it remains profitable for them to do so.

This pattern of WHOIS data reuse doesn’t just extend across a few weeks or months. Very often, if a spammer, phisher or scammer can get away with re-using the same WHOIS details over many years without any deleterious effects to their operations, they will happily do so. Why they may do this is their own business, but nevertheless it makes WHOIS an incredibly powerful tool for tracking threat actors across multiple networks, registrars and Internet epochs.

All domain registrars offer free or a-la-carte privacy protection services that mask the personal information provided by the domain registrant. Most cybercriminals — unless they are dumb or lazy — are already taking advantage of these anyway, so it’s not clear why masking domain registration for everyone is going to change the status quo by much.

It is true that some domain registrants do take advantage of WHOIS privacy services, but based on countless investigations I have conducted using WHOIS to uncover cybercrime businesses and operators, I’d wager that cybercrooks more often do not use these services. Not infrequently, when they do use WHOIS privacy options there are still gaps in coverage at some point in the domain’s history (such as when a registrant switches hosting providers) which are indexed by historic WHOIS records and that offer a brief window of visibility into the details behind the registration.

This is demonstrably true even for organized cybercrime groups and for nation state actors, and these are arguably some of the most sophisticated and savvy cybercriminals out there.

It’s worth adding that if so many cybercrooks seem nonchalant about adopting WHOIS privacy services it may well be because they reside in countries where the rule of law is not well-established, or their host country doesn’t particularly discourage their activities so long as they’re not violating the golden rule — namely, targeting people in their own backyard. And so they may not particularly care about covering their tracks. Or in other cases they do care, but nevertheless make mistakes or get sloppy at some point, as most cybercriminals do.

The GDPR does not apply to businesses — only to individuals — so there is no reason researchers or anyone else should be unable to find domain registration details for organizations and companies in the WHOIS database after May 25, right?

It is true that the European privacy regulations as they relate to WHOIS records do not apply to businesses registering domain names. However, the domain registrar industry — which operates on razor-thin profit margins and which has long sought to be free from any WHOIS requirements or accountability whatsoever — won’t exactly be tripping over themselves to add more complexity to their WHOIS efforts just to make a distinction between businesses and individuals.

As a result, registrars simply won’t make that distinction because there is no mandate that they must. They’ll just adopt the same WHOIS data collection and display polices across the board, regardless of whether the WHOIS details for a given domain suggest that the registrant is a business or an individual.

But the GDPR only applies to data collected about people in Europe, so why should this impact WHOIS registration details collected on people who are outside of Europe?

Again, domain registrars are the ones collecting WHOIS data, and they are most unlikely to develop WHOIS record collection and dissemination policies that seek to differentiate between entities covered by GDPR and those that may not be. Such an attempt would be fraught with legal and monetary complications that they simply will not take on voluntarily.

What’s more, the domain registrar community tends to view the public display of WHOIS data as a nuisance and a cost center. They have mainly only allowed public access to WHOIS data because ICANN’s contracts state that they should. So, from registrar community’s point of view, the less information they must make available to the public, the better.

Like it or not, the job of tracking down and bringing cybercriminals to justice falls to law enforcement agencies — not security researchers. Law enforcement agencies will still have unfettered access to full WHOIS records.

As it relates to inter-state crimes (i.e, the bulk of all Internet abuse), law enforcement — at least in the United States — is divided into two main components: The investigative side (i.e., the FBI and Secret Service) and the prosecutorial side (the state and district attorneys who actually initiate court proceedings intended to bring an accused person to justice).

Much of the legwork done to provide the evidence needed to convince prosecutors that there is even a case worth prosecuting is performed by security researchers. The reasons why this is true are too numerous to delve into here, but the safe answer is that law enforcement investigators typically are more motivated to focus on crimes for which they can readily envision someone getting prosecuted — and because very often their plate is full with far more pressing, immediate and local (physical) crimes.

Admittedly, this is a bit of a blanket statement because in many cases local, state and federal law enforcement agencies will do this often tedious legwork of cybercrime investigations on their own — provided it involves or impacts someone in their jurisdiction. But due in large part to these jurisdictional issues, politics and the need to build prosecutions around a specific locality when it comes to cybercrime cases, very often law enforcement agencies tend to miss the forest for the trees.

Who cares if security researchers will lose access to WHOIS data, anyway? To borrow an assertion from the Internet Governance article, “maybe it’s high time for security researchers and businesses that harvest personal information from WHOIS on an industrial scale to refine and remodel their research methods and business models.”

This is an alluring argument. After all, the technology and security industries claim to be based on innovation. But consider carefully how anti-virus, anti-spam or firewall technologies currently work. The unfortunate reality is that these technologies are still mostly powered by humans, and those humans rely heavily on access to key details about domain reputation and ownership history.

Those metrics for reputation weigh a host of different qualities, but a huge component of that reputation score is determining whether a given domain or Internet address has been connected to any other previous scams, spams, attacks or other badness. We can argue about whether this is the best way to measure reputation, but it doesn’t change the prospect that many of these technologies will in all likelihood perform less effectively after WHOIS records start being heavily redacted.

Don’t advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning obviate the need for researchers to have access to WHOIS data?

This sounds like a nice idea, but again it is far removed from current practice. Ask anyone who regularly uses WHOIS data to determine reputation or to track and block malicious online threats and I’ll wager you will find the answer is that these analyses are still mostly based on manual lookups and often thankless legwork. Perhaps such trendy technological buzzwords will indeed describe the standard practice of the security industry at some point in the future, but in my experience this does not accurately depict the reality today.

Okay, but Internet addresses are pretty useful tools for determining reputation. The sharing of IP addresses tied to cybercriminal operations isn’t going to be impacted by the GDPR, is it?

That depends on the organization doing the sharing. I’ve encountered at least two cases in the past few months wherein European-based security firms have been reluctant to share Internet address information at all in response to the GDPR — based on a perceived (if not overly legalistic) interpretation that somehow this information also might be considered personally identifying data. This reluctance to share such information out of a concern that doing so might land the sharer in legal hot water can indeed have a chilling effect on the important sharing of threat intelligence across borders.

According to the Internet Governance article, “If you need to get in touch with a website’s administrator, you will be able to do so in what is a less intrusive manner of achieving this purpose: by using an anonymized email address, or webform, to reach them (The exact implementation will depend on the registry). If this change is inadequate for your ‘private detective’ activities and you require full WHOIS records, including the personal information, then you will need to declare to a domain name registry your specific need for and use of this personal information. Nominet, for instance, has said that interested parties may request the full WHOIS record (including historical data) for a specific domain and get a response within one business day for no charge.”

I’m sure this will go over tremendously with both the hacked sites used to host phishing and/or malware download pages, as well as those phished by or served with malware in the added time it will take to relay and approve said requests.

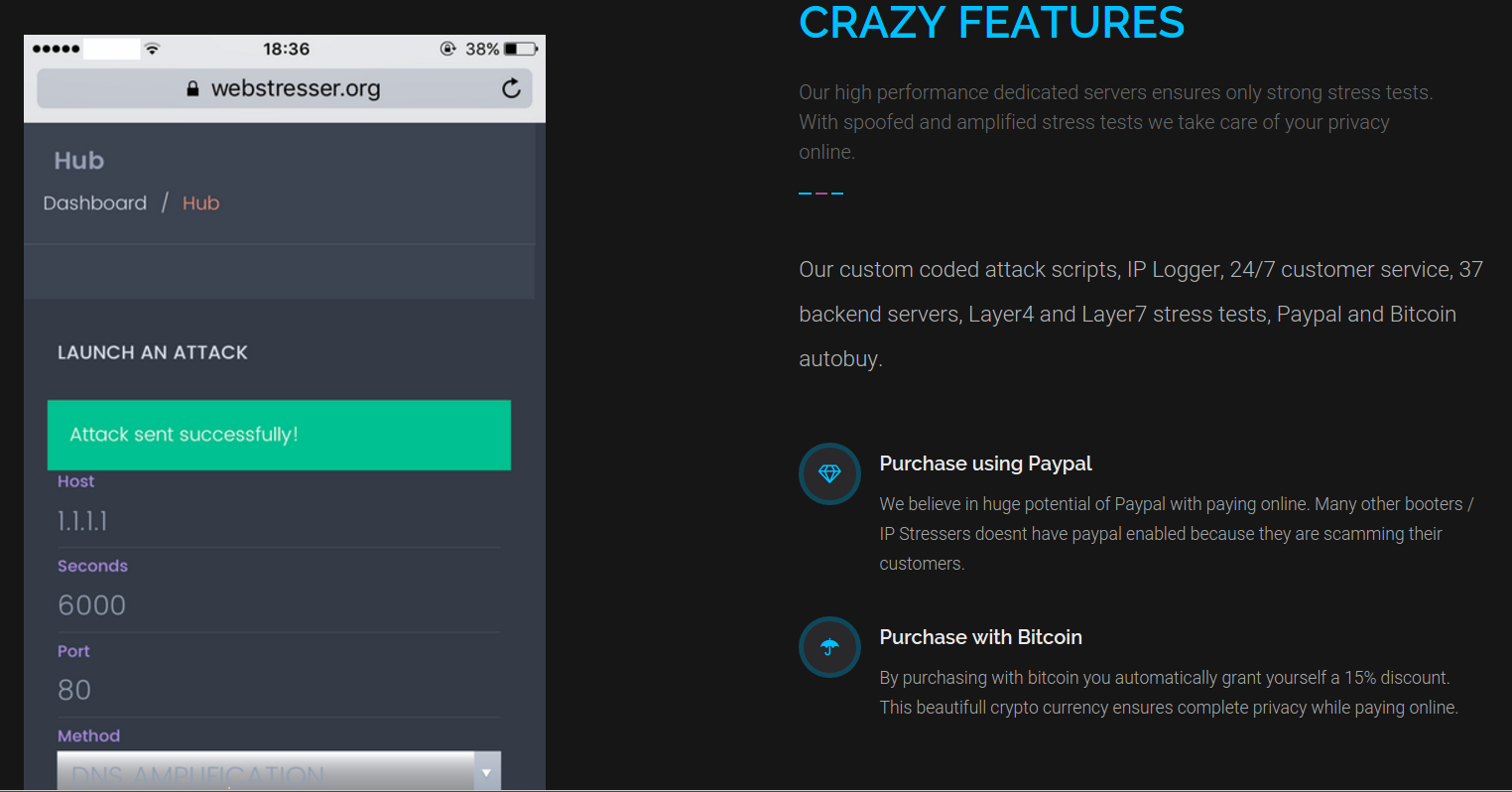

According to a Q3 2017 study (PDF) by security firm Webroot, the average lifespan of a phishing site is between four and eight hours. How is waiting 24 hours before being able to determine who owns the offending domain going to be helpful to either the hacked site or its victims? It also doesn’t seem likely that many other registrars will volunteer for this 24-hour turnaround duty — and indeed no others have publicly demonstrated any willingness to take on this added cost and hassle.

I’ve heard that ICANN is pushing for a delay in the GDPR as it relates to WHOIS records, to give the registrar community time to come up with an accreditation system that would grant vetted researchers access to WHOIS records. Why isn’t that a good middle ground?

It might be if ICANN hadn’t dragged its heels in taking GDPR seriously until perhaps the past few months. As it stands, the experts I’ve interviewed see little prospect for such a system being ironed out or in gaining necessary traction among the registrar community to accomplish this anytime soon. And most experts I’ve interviewed predict it is likely that the Internet community will still be debating about how to create such an accreditation system a year from now.

Hence, it’s not likely that WHOIS records will continue to be anywhere near as useful to researchers in a month or so than they were previously. And this reality will continue for many months to come — if indeed some kind of vetted WHOIS access system is ever envisioned and put into place.

After I registered a domain name using my real email address, I noticed that address started receiving more spam emails. Won’t hiding email addresses in WHOIS records reduce the overall amount of spam I can expect when registering a domain under my real email address?

That depends on whether you believe any of the responses to the bolded questions above. Will that address be spammed by people who try to lure you into paying them to register variations on that domain, or to entice you into purchasing low-cost Web hosting services from some random or shady company? Probably. That’s exactly what happens to almost anyone who registers a domain name that is publicly indexed in WHOIS records.

The real question is whether redacting all email addresses from WHOIS will result in overall more bad stuff entering your inbox and littering the Web, thanks to reputation-based anti-spam and anti-abuse systems failing to work as well as they did before GDPR kicks in.

It’s worth noting that ICANN created a working group to study this exact issue, which noted that “the appearance of email addresses in response to WHOIS queries is indeed a contributor to the receipt of spam, albeit just one of many.” However, the report concluded that “the Committee members involved in the WHOIS study do not believe that the WHOIS service is the dominant source of spam.”

Do you have something against people not getting spammed, or against better privacy in general?

To the contrary, I have worked the majority of my professional career to expose those who are doing the spamming and scamming. And I can say without hesitation that an overwhelming percentage of that research has been possible thanks to data included in public WHOIS registration records.

Is the current WHOIS system outdated, antiquated and in need of an update? Perhaps. But scrapping the current system without establishing anything in between while laboring under the largely untested belief that in doing so we will achieve some kind of privacy utopia seems myopic.

If opponents of the current WHOIS system are being intellectually honest, they will make the following argument and stick to it: By restricting access to information currently available in the WHOIS system, whatever losses or negative consequences on security we may suffer as a result will be worth the cost in terms of added privacy. That’s an argument I can respect, if not agree with.

But for the most part that’s not the refrain I’m hearing. Instead, what this camp seems to be saying is if you’re not on board with the WHOIS changes that will be brought about by the GDPR, then there must be something wrong with you, and in any case here a bunch of thinly-sourced reasons why the coming changes might not be that bad.

Last week, Facebook

Last week, Facebook