How we fixed DRM in Portugal (and so can you)

After 15 years of trying to solve the DRM problem, the Portuguese Association for Free Software ANSOL and the Association for Free Education AEL finally managed to get what they sought: a fix to the DRM situation in Portugal.

Digital Restrictions Management (originally introduced by the entertainment industry as Digital Rights Management), are technologies that prevent, control, or restrict the use of hardware, software, or other creative works like books, films, music, etc.. They are also known as anti-copy technologies. In 1998 in USA and in 2001 in Europe, these technologies were given legal protection by the lawmakers. Copyright holders convinced the lawmakers that they needed DRM to be protected by the law in order to stop file-sharing without commercial purposes. This legal protection meant that breaking the DRM started to be illegal or a crime. In Portugal, for example, breaking the DRM had a penalty of up to one year in prison, until 2017. Even if you did something legal.

In Europe, we have a set of copyright exceptions to guarantee fundamental rights. These are uses of the work we are allowed to do without having to ask permission to the rightholders and authors. Depending on the law in your country, you can make a private copy, use works or parts of works for education and scientific research, quotations for criticism or review. Libraries and other cultural heritage institutions have a set of exceptions that allow them to make available works to the public and to digitally preserve those works, and the press also has a set of exceptions to guarantee the right to information. These exceptions are described in article 5 of the InfoSoc European Directive.

When lawmakers gave legal protection to DRM, they didn't really protect these exceptions, which meant that while citizens have these rights, they cannot exercise them, since there is no way to exercise most of them without breaking the DRM. For instance, if you bought a music CD and your country has a private copy exception[^1], you can make a digital copy to listen to its music on your mobile phone. But, if the CD has DRM, while you still have the right to make a copy, you cannot exercise it, since there is no way to make a private copy of a DRMed CD without breaking the DRM, which you are not allowed to do.

In Portugal, this is no longer a problem. In the next few paragraphs, we'll tell you about how we decided this situation wasn't acceptable, what did we do about it, and what did we achieve.

Document yourselfWhat is DRM and how does it work?

The first step is to understand what DRM is and how does it work. The science fiction writer Cory Doctorow has an extensive set of talks, articles, and books about the subject. His talk to the Microsoft Research Group in 2004, where he explains why DRM systems don't work and why they are bad for society, for business, and for artists is still, in our opinion, one of the best articles to understand the problem. You can find the text in his book "Content".

Defective by Design, a campaign from Free Software Foundation, and DRM.info from Free Software Foundation Europe are also important resources to get information from. On the International Day Against DRM, FSFE also published its Software Freedom Podcast with Cory Doctorow dedicated to DRM.

Keep in mind that the main goal of this step is for you to be able to explain the DRM problem to people that are not technological savvy. It is also a good idea to think about examples that users can face on a day to day basis and thus are easier to relate to.

Harder than learning all there is to know about DRM and how it works is to make others learn that too. However, only by getting our policy makers learn about it were we able to have them consider that this could be a problem they had to solve.

The arguments used by those in favour of DRM and how to deconstruct them

One important step is to know what arguments those that (apparently) defend DRM use. These arguments also change through time.

A common flaw of a conversation about DRM with rightholders is one where, at first, they say they need DRM to stop illegal copying. When faced with the fact that DRM law has been around for two decades without any impact on file sharing without commercial purposes, or when you explain that DRM puts both locks and keys in the hands of those they don't wish to get the lock open, rightholders start changing their arguments, saying things like that they are aware DRM does not stop those with knowledge to break the locks, but that the intention is to stop the common citizen from sharing the works (at which point you can note that once the DRM is broken, the only thing the "common citizen" needs to do is a search on the Web).

We say "apparently in favour", however, since at some point during this long battle, we got to a point where the arguments were simply "we don't even want legal protection to DRM either", or "we only have this because the European directive demands it".

What does the European Directive say?

The next step is to check what the European Directive say about DRM. You'll want to check articles 6 and 7 of the InfoSoc. There you can find what the law defines as DRM and how Member States have or can transpose to their national law.

Usually, the law does not refer the term DRM, instead it refers "technological measures" or "protection measures".

What does your national law say?

After checking the European Directive, you will need to read the law in your own country to verify how was the directive transposed into national law. In particular, you need to check:

What copyright exceptions has your country?

What is the definition of DRM in the law?

What happens when an user breaks the DRM?

Does the law offer some kind of solution for the cases where the user needs to exercise a copyright exception?

Answering these questions will help you understand what is the case in you country regarding DRM, and after that you can design the best strategy to fix the problem. Although the European Directive imposes some level of harmonisation, the situation can be different from country to country. For example, Poland never implemented these rules.

Test the law

In the case of Portugal, the law considered that breaking DRM was a crime, but it also had an article saying the DRM should not prevent citizens from using the copyright exceptions, like private copying, or using an excerpt of a work for educational purposes, scientific research, etc. This is important because the European Directive, in its article 6.4, mandates Member States to ensure users can benefit from the copyright exceptions, which means that other countries must have some kind of process in place to allow citizens to make copies of DRMed works. Of course, there is also a high probability that solution does not work. It was the case in Portugal.

The Portuguese law said that when DRM prevented a citizen from making use of a copyright exception, the citizen could contact the General Inspection of Cultural Activities (IGAC), a public institution from the Ministry of Culture, and ask for the "means" to make the copy, instead of breaking the DRM himself, because, the law also stated, rightholders had to deposit those "means" in IGAC. In summary: rightholders should deposit the "means" to open the DRM in IGAC, then citizens would ask IGAC for those "means" in order to exercise a legal use, like a private copy. We never knew what the law meant by "means" - it was assumed those would be the keys IGAC would be able to use in order to open the DRM locks.

Knowing how we were supposed to be able to exercise our rights, we decided to test the law: we got a DVD with DRM, contacted IGAC telling them we wanted to make a private copy (which is a copyright exception in Portugal, and thus a legal action), and asked them for the "means" to make that private copy without breaking the DRM (actually, the first request we made was for the means so we could legally watch a DVD with DRM on our GNU/Linux laptop, but IGAC didn't understand the request, so we used the private copy exception, which seems to be easier to understand).

After pointing IGAC to the law and which exact articles were we trying to exercise, they told us they couldn't give us what we asked since they didn't have those "means", as the rightholders had not deposit them, a situation the law didn't foresee (and as such, there was no penalty for rightholders that didn't make such a deposit).

We made sure to get a written statement from IGAC saying they didn't have those "means" (either to that DVD or anything else), which was important for us to use as proof that the law at that moment didn't work.

Raise awareness and educate

Since the beginning, it is important to raise awareness, have people talk about DRM, to show that citizens being prevented from exercising a copyright exception is not acceptable. The problem with DRM is mainly a legal one, not technical. As Doctorow says, "DRM systems are usually broken in minutes, sometimes days. Rarely, months. It's not because the people who think them up are stupid. It's not because the people who break them are smart. It's not because there's a flaw in the algorithms. At the end of the day, all DRM systems share a common vulnerability: they provide their attackers with ciphertext, the cipher and the key. At this point, the secret isn't a secret anymore".

Politicians will only fix the law if they know there are citizens voicing their concerns about it. If no one cares about a certain problem, why would they spend time fixing it?

The Public

We made several actions to raise public awareness, too many to list here. Some of the ones we believe helped the most are:

Inspired by the Defective by Design campaign actions, we went to cinemas that were showing movies from pro-DRM majors and distributed flyers, talking about DRM to the people that went to see those movies. One example was the première of the movie "Pirates of Caribbean" in Portugal, back in 2007. You can watch a small video by clicking in the image below and

read about it here (in Portuguese).

DRM Action Video

We set up the DRM-PT website, where we published content about the problems of DRM, in Portuguese. Besides raising awareness, a blog or a website will be helpful for you to register developments, examples of problems faced by citizens when encountering DRM, and arguments, that you will need to use later on.

Also inspired by Defective by Design, we maintained in the website a list of publishers and companies, including Portuguese ones, that use DRM, recommending people to avoid those companies, brands or products.

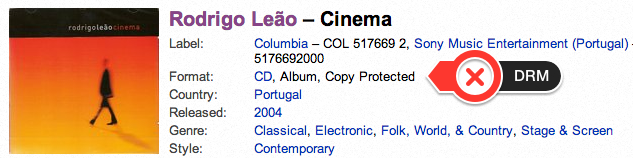

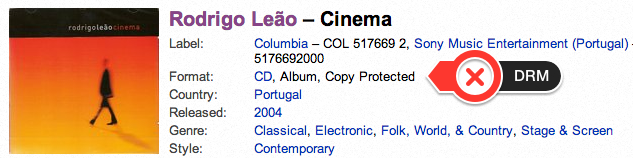

We also wrote a bit about how to check if a product has DRM:

Example of a CD with DRM

We also used the website to maintain a list of frequently asked questions (FAQ) and a press section, where we gathered articles, presentations, and other media about the problems of DRM.

From the start we boycotted pro-DRM companies and, most importantly, talked about it. For example, when we were planning on buying something (CD, DVD, eBook, etc.) and then find out it had DRM, we would write about it on our personal blogs. On the other hand, each time we found something that could but didn't have DRM, we would also talk about the purchase, praising the author, the publisher, and the store.

We used social networks to discuss the problem. When someone asked which eBook e-reader or app should they buy or use, we would advise against those that had or promote DRM, explaining why and pointing to the DRM-PT website. We never encouraged anyone to break DRM, even for legal purposes, explaining instead that what they wanted was lawful, the way to get it was illegal, and that's why we wanted to see the law changed.

We also organised and participated in conferences and other events, taking every opportunity to talk about the DRM problem.

Politicians

Because the main problem with DRM is legal, sooner or later you will have to start talking with politicians - the law makers, to make them aware of the problem and to convince them to change the law.

Again, here is a non-exhaustive list of the things we did to achieve this:

We sent emails to all political parties in the national Parliament explaining the problem, refuting the arguments from those that apparently defend DRM, pointing out the law didn't work, and asking them to consider changing the law. While some won't reply, others will, and, even if they aren't convinced, they are still open to listen to you, giving you another chance to present your arguments.

In events we organised or participated, we always tried to include a talk on DRM and invited politicians from all the political spectrum to talk about the issue. They started to show up. Likewise, when political parties had events on related subjects (like open education or open science) we would go and ask questions at the end, pointing out how DRM harms those activities. Of course, we would also attend and participate in events organized by other institutions.

DRM is an issue that has no political spectrum. Left or right, conservative or liberal, you can argue against DRM with parties positioned anywhere in the political compass. It is important to understand what kind of concerns the politician you are talking to has. Some will be more concerned with competition and the markets, others with education or science, others still with fundamental rights, public domain... But there is an argument for each of these topics: DRM destroys competition and distorts the market, harms the public domain and property rights (even on cars or coffee machines.

Eventually, if things go well, a law proposal will reach the Parliament. This is the time where you can send your contributions and arguments, and if you represent an association you can ask for meetings and to be heard. It is important to be aware that the law proposal isn't the end of the road: by now you created the space to debate the subject, but this is when it is time to have it debated, and you will need to convince a majority in your parliament that the law must be changed.

Before the discussion in the plenary took place, we made small books, with an hole in them, and a physical lock preventing the books from being opened. We sent the locked books and the keys to the members of the parliament. The book itself explained the DRM problem in the law, and the analogy with the item they were just reading.

During the plenary discussion, one of the members of the Parliament used the notebook to explain the problem with the DRM:

DRM Law Discussion in Portuguese Parliament

It also helps to get leverage from other laws. Between 2011 and 2015, Portuguese Governments tried to change the private copy exception levies, and each of those times we used the opportunity to point out that, because of DRM, citizens weren't even able to exercise the exception. Note that citizens pay to have the private copy exception every time they buy a computer, a mobile phone, or any other device that makes copies or have some kind of storage. If your country has a private copy exception there is a high probability you are also paying an extra in the devices you buy.

Persist

First you need to know and care, then you need to get others to know and care. Afterwards, you raise awareness amongst policy makers up to a point where law proposals exist. Even then, there is work to be done. It will not be easy or quick. We had two political parties submitting proposals to change the law, twice. In 2013, both the proposals were rejected. Only in 2017, one of them was approved by the Parliament. But don't give up. If we did it, so can you!

Work within the framework

Legal justification for DRM is enshrined in an European directive, and it doesn't matter what you think about it: Member States need to comply with it. That can even work at your advantage: after all, the directive states that Member States need to ensure users can benefit from the copyright exceptions, for instance. But that also means that you will hear the argument that there is nothing to be done about this, since the directive mandates it.

It is important to make sure the proposed change doesn't go against what is in the Directive. The European Directive does not allow Member States to allow their citizens to break DRM, not even for legal purposes.

Fortunately, now that Portugal has found a fix, you might be able to point out to it, and propose the adoption of a similar solution.

Note that there is a difference between getting your law makers to accept that there is a problem, and working on a solution, and it will be helpful if you present them with both: "Hey, you have a problem here, and here's a way you can solve it".

The approach we found acceptable was to work the definition of the DRM, excluding copyright exceptions. In bold, the part that was added to the law:

"Article 217º […] the expression “technological measures” means any technology, device or component that, in the normal course of its operation, is designed to prevent or restrict acts, in respect of protected works, that are not exceptions to the copyright, provided in the nº 2 of the article 75º, in the article 81º, in the nº4 of the article 152º and in the nº1 of the article […]"

Making it clear: if a technology prevents a Portuguese citizen from making use of a copyright exception (private copy, education, commentary, critic, scientific research etc.), then that technology is not considered DRM by the law. Not having legal protection, it can be lawfully broken.

On the other hand, if a technology prevents a citizen from making an unlawful use (file-sharing, which is not permitted in Portugal, for example) then that technology is considered DRM by the law and cannot be broken.

So, the same technology can be considered both DRM and not DRM depending on the unlawful or lawful purpose the citizen has.

Make the (apparent) opposition talk

During the discussions in the Portuguese Parliament, we pointed out that the law at that time didn't work since IGAC didn't have the "means" needed. We gave one step further and claimed that, if they didn't want to change the law as we proposed, they had to at least change it to establish a punishment for the rightholders not handing those "means" over, and that the parliament should invite them to speak, and explain why they didn't do it.

Both IGAC and the rightholders were called to the Parliament. Both admitted they didn't have the keys, and the rightholders even added they would never get the keys from the companies that made the DRM systems.

Present your alternative

At this point, our feeling was that most members of the parliament knew we were right: the solution the law had didn't and couldn't work. So, they were ready to approve the change in the law. The approved law was proposed by the Left Bloc, with the votes in favour of the Socialist Party, the Communist Party, the Greens Party, and the Persons, animals, and Nature Party and was promulgated by the President of Portugal on 2nd of June of 2017.

The law also prohibited DRM in public domain works, in new editions of public domain works, and in works published by public entities or funded by public money.

Start acting at an European Level

If the European Directive made it clear that copyright exceptions were out of the scope of the DRM - after all it was never the intention of the lawmaker to remove fundamental rights - then it would be easier for all the Member States to solve the problem.

At the beginning of the discussions regarding the recently approved Copyright Directive we met with the Member of the European Parliament, Ms. Julia Reda, and talked about what we did in Portugal and the possibility to propose an amendment regarding DRM in the directive, which she did. The proposal was to make sure copyright exceptions were out of the scope by adding to the definition of the DRM: and which are not authorised by national or Union law:

“For the purposes of this Directive, the expression "technological measures" means any technology, device or component that, in the normal course of its operation, is designed to prevent or restrict acts, in respect of works or other subject-matter, which are not authorised by the rightholder of any copyright or any right related to copyright as provided for by law or the sui generis right provided for in Chapter III of Directive 96/9/EC, and which are not authorised by national or Union law.”

The amendment was voted in the IMCO Committee (Internal Market and Consumer Protection), but it was rejected by one vote.

Conclusion

Awareness and knowledge are important for you to embrace and get yourself involved in something you want to change. But it is not enough: you need to make sure that those are transmitted, as you need to reach and catch the attention of those who can actually make the change happen. It is a process that involves persistence, but it can be achieved, and there are ways to make it easier. Make sure you have clear examples of what are the problems, and make it clear that even those benefiting from them admit there are problems. But don't present a problem without also presenting a potential solution.

This is an experience we are sure we will take a few lessons learned from into future challenges. But this particular topic isn't solved yet. There is now a directive transposition in Portugal that, we believe, makes more sense. It is time to take this one level further, and see other Member States following this steps.

Are you up to it?

This article was written by Paula Simões and Marcos Marado. They can be contacted at paulasimoes[at]gmail[dot]com and marcos.marado[at]ansol[dot]org , and they are available to discuss further about this subject, if you have any questions, or want to fix the DRM problem in your country too.

Support FSFE

The three discussed options for the location of the NTP. Source: BEREC

The network termination point is at location A. This means that

routers and modems are in the user's control who can decide which

device to use – either the one recommended and provided by the ISP

or one by a third party. That would result in Router Freedom.

The NTP is at B. This means that only the modem (so the device

connecting to the ISP) will be part of the ISP's network, but

routers or media boxes will be in the user's domain.

The NTP is at C. That's the most restrictive option as it results

in the modem and router or a combined device being under the

control of the ISP solely.

The three discussed options for the location of the NTP. Source: BEREC

The network termination point is at location A. This means that

routers and modems are in the user's control who can decide which

device to use – either the one recommended and provided by the ISP

or one by a third party. That would result in Router Freedom.

The NTP is at B. This means that only the modem (so the device

connecting to the ISP) will be part of the ISP's network, but

routers or media boxes will be in the user's domain.

The NTP is at C. That's the most restrictive option as it results

in the modem and router or a combined device being under the

control of the ISP solely.

Example of a CD with DRM

Example of a CD with DRM

DRM Law Discussion in Portuguese Parliament

It also helps to get leverage from other laws. Between 2011 and 2015, Portuguese Governments tried to change the private copy exception levies, and each of those times we used the opportunity to point out that, because of DRM, citizens weren't even able to exercise the exception. Note that citizens pay to have the private copy exception every time they buy a computer, a mobile phone, or any other device that makes copies or have some kind of storage. If your country has a private copy exception there is a high probability you are also paying an extra in the devices you buy.

Persist

DRM Law Discussion in Portuguese Parliament

It also helps to get leverage from other laws. Between 2011 and 2015, Portuguese Governments tried to change the private copy exception levies, and each of those times we used the opportunity to point out that, because of DRM, citizens weren't even able to exercise the exception. Note that citizens pay to have the private copy exception every time they buy a computer, a mobile phone, or any other device that makes copies or have some kind of storage. If your country has a private copy exception there is a high probability you are also paying an extra in the devices you buy.

Persist "So far no. Sympathies for the cause are present, and the city is also active in the field. But the motion comes from a group that cannot convince in this point."

"So far no. Sympathies for the cause are present, and the city is also active in the field. But the motion comes from a group that cannot convince in this point."

"I am afraid there is no majority for this in this legislature. It is a pity, but politics is also a question of opportunities."

"I am afraid there is no majority for this in this legislature. It is a pity, but politics is also a question of opportunities."