New Improvements in the CC Search Browser Extension

lundi 7 décembre 2020 à 19:38This is part of a series of posts introducing the projects built by open source contributors mentored by Creative Commons during Google Summer of Code (GSoC) 2020 and Outreachy. Mayank Nader was one of those contributors and we are grateful for his work on this project.

The CC Search Browser Extension allows users to search, filter, and use images in the Public Domain and under Creative Commons licenses. It is heavily inspired by CC Search but at the same time, it offers an experience that is more personalized and collaborative. One of the primary goals of the extension is to complement the user’s workflow and allow them to concentrate on what’s important.

Recently, there have been many improvements to the CC Search Browser Extension and I’ll go through the significant changes in this post.

- New filters

Previously, the extension only supported filtering the content using license, sources, and use case. Now, the extension also supports filtering by image type, file type, aspect ratio, and image size. This will allow users to be more precise in their queries when searching.

- Browsing by source

The extension now has a dynamically updated “sources” section. This opens an avenue for exploration of all the 40+ sources which are currently available in the CC Catalog. This is advantageous for users who are not familiar with the type of content a particular source provides. They might run into a source that has a huge catalog of high-quality images that they are looking for.

- Search by tags

Most of the images have some tags associated with them, which are now shown in the image-detail section. Image tags will allow users to incrementally make their queries better and more specific.

- Related images

In the image detail section of any particular image, you can now see several recommendations. This will help users find a variety of images that fit their requirements and also explore the images that would not usually show up on the initial pages of the search result.

- Improvement to the bookmarks section

The bookmarks section is an important part of the extension. While searching, if you find images that you might use later you can bookmark and save them in the extension.

The bookmarks section has undergone some crucial improvements which have made it significantly faster. Also, now the extension will be able to hold 300 bookmarks (the old version had a limit of only 50).

We made sure that the updates to the bookmarks section do not remove any previously saved bookmarks. If a user has some old bookmark files that they are using for sharing or archiving, the extension will still be able to recognize and parse those files.

Comparing the rendering of the bookmarked images in the old version and the new version demonstrates the improvement in performance.

- Improved UI

Updating the UI of the extension was necessary to make space for all of the improvements. All the workflows and features in the old version of the extension have been updated to make the new UI very intuitive.

- Demonstrating a general use case

As I said in the introduction of this post, rather than complicating the workflow of the user, the extension’s goal is to complement it. The extension makes it easier to add images and their attributions to a blog post in WordPress, for example. After you have searched and bookmarked the images, it’s a matter of a few clicks. You can replicate this on Medium, Blogger, or any modern blogging platform. (Evident here!)

- Installation

The latest version of the extension is available for installation on Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Opera, and Microsoft Edge.

If you are already using the extension, then the extension should have auto-updated. If it has not, the instructions to manually update are written under the FAQ tab in the settings page.

Join the community

Come and tell us about your experience on the Creative Commons Slack via the slack channel: #cc-dev-browser-extension.

Also, check out the project on Github. You can contribute in the form of bug reports, feature requests, or code contributions.

The post New Improvements in the CC Search Browser Extension appeared first on Creative Commons.

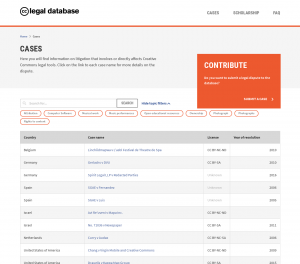

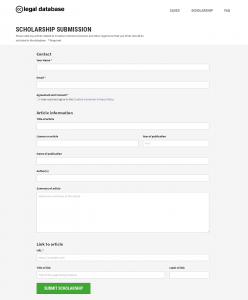

You can also contribute relevant information to the database within the site, a project that the CC Legal team will be rolling out in the near future. Once active, you can submit a

You can also contribute relevant information to the database within the site, a project that the CC Legal team will be rolling out in the near future. Once active, you can submit a