European Parliament Must Protect Scientific Research

jeudi 7 septembre 2017 à 09:00

In June we asked the European Parliament to redouble their efforts to make much-needed improvements to the EU copyright reform. We called on the Parliament to spearhead crucial changes that promote creativity and business opportunities, enable research and education, and protect user rights in the digital market.

Despite this strong ask, the direction of the copyright reform is getting worse, not better.

This week Creative Commons and major organisations from the library, research, education, and digital rights community sent a letter to the European Parliament’s Legal Affairs Committee calling on it to protect open access and open science in the context of the Commission’s draft Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market. Additional signatories are encouraged to join the letter.

Of particular concern are two parts of the draft directive: Article 11 (press publisher’s right) and Article 13 (platform content filtering). We believe that these provisions will create burdensome and harmful restrictions on access to scientific research and data, as well as on the fundamental rights of freedom of information, directly contradicting the EU’s own ambitions in the field of Open Access and Open Science.

The press publisher’s right already poses a significant threat to an informed and literate society. Links to news and the use of titles, headlines and fragments of information could now become subject to licensing. The extension of this controversial proposal to cover academic publications, as proposed by the Parliament’s Research Committee, significantly worsens an already bad situation. This type of arrangement is unequivocally harmful to access to scientific and scholarly information—most of which has already been paid for from by the public funds, and whose raison d’être is to be read as widely as possible in order to contribute to the scientific enterprise. It flies in the face of open access publishing, whose authors have chosen to share their research outputs under permissive licenses for the benefit of all. And it directly conflicts with other provisions in the EU’s copyright reform meant to improve research processes and outcomes, such as the mandatory copyright exception for text and data mining.

Article 13 threatens the accessibility of scientific articles, publications and research data made available through over 1250 repositories that European non-profit institutions and academic communities. These repositories, which are essential for Open Access and Science in Europe, are likely to face significant additional operational costs associated with implementing new filtering technology and the legal costs of managing the risks of intermediary liability.

Both Articles 11 and 13 should be removed from the proposal.

Our letter also touches on other important issues such as the exception for text and data mining (Article 3) and the exception for educational purposes (Article 4). We ask the Legal Affairs Committee to improvement these and other Articles so they to provide better support for teaching, learning, and new forms of research.

You can read the full letter below.

Are you interested in receiving updates about our work copyright reform efforts from Creative Commons and our partners in policy? Sign up to our list. We’ll email you no more than once per month!

EU copyright reform threatens Open Access and Open Science

Open letter to the members of the Legal Affairs Committee in the European Parliament

We represent a large group of European academic, library, education, research and digital rights communities and we are writing to express our alarm at the draft Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market, and in particular at the potential impact of Articles 11 and 13. We are concerned that these provisions will create burdensome and harmful restrictions on access to scientific research and data, as well as on the fundamental rights of freedom of information, directly contradicting the EU’s own ambitions in the field of Open Access and Open Science.

We therefore urge the Legal Affairs Committee to remove Articles 11 and 13 from the draft Directive. Furthermore, the Committee should ensure that Articles 3 to 9 support new forms of research and education and not work against them.

A U-turn on Open Science?

- We believe that increased digital access, data analytics and open information flows will increase innovation in Europe. The European Commission’s Horizon 2020 programme similarly supports open access to scientific publications and research data as essential drivers of EU global competitiveness. The EU has set an example internationally with its extensive policy work, for example by including Open Access in one of its six European Research Area (ERA) priorities. Moreover in 2016 at the Competitiveness Council, all of Europe’s ministers of science, innovation, trade and industry committed to Open Access to scientific publications as the default option for publicly funded research results by 2020. Open Science is increasingly accepted by governments and industry as a means not only to accelerate innovation, but also to ensure faster access to information for citizens.

- However, several proposed elements of Articles 11 and 13 will prevent the EU from realizing the significant potential of Open Access and Open Science to promote scientific discovery and progress, and may thereby reduce the impact of European research worldwide.

The Ancillary Right – Putting the brakes on knowledge-sharing and building walls around already open publications and data

- Article 11 already poses a significant threat to an informed and literate society. Links to news and the use of titles, headlines and fragments of information could now become subject to licensing. Terms could make the last two decades of news less accessible to researchers and the public, leading to a distortion of the public’s knowledge and memory of past events. Art. 11 would furthermore place EU law in contravention with the Berne Convention, whose Art. 2(8) excludes news of the day and ‘mere items of press information’ and ‘press summaries’ from protection.

- The extension of this controversial proposal to academic publications, as proposed by the ITRE Committee, significantly worsens an already bad situation. It would provide academic publishers additional legal tools to restrict access, going against the increasingly widely accepted practice of sharing research. This will limit the sharing of open access publications and data which currently are freely available for use and reuse in further scientific advances. If the proposed ancillary right is extended to academic publications, researchers, students and other users of scientific and scholarly journal articles could be forced to ask permission or pay fees to the publisher for including short quotations from a research paper in other scientific publications. This will seriously hamper the spread of knowledge. The proposed ancillary right further conflicts with the Berne Convention’s Article 10(1), which provides a mandatory exception for quotation, as well as posing risks to freedom of speech.

- Prior experiments with the press publishers’ right have also failed from an economic standpoint. No impact assessment has been carried out, no evidence produced, and no consultation conducted around the ramifications of extending Art. 11 to academic publishers.

- In addition, academic publishers usually acquire rights to the works they publish when signing contracts with their authors. Publishers already have all the rights they need, thus ancillary rights don’t make sense.

Filtering obligations – Undermining the foundations of Open Access

- The provisions of Article 13 threaten the accessibility of scientific articles, publications and research data made available through over 1250 repositories that European non-profit institutions and academic communities. These repositories, which are essential for Open Access and Science in Europe, are likely to face significant additional operational costs associated with implementing new filtering technology and the legal costs of managing the risks of intermediary liability. The additional administrative burdens of policing this content would add to these costs. Such repositories, run on a not-for-profit basis, are not equipped to take on such responsibilities, and may face closure. This would be a significant blow, creating new risks for implementing funder, research council and other EU Open Access policies.

Text and Data Mining – The risks to scientific values

- Regarding Article 3, we welcome amendments that expand the exception for text and data mining (TDM) to allow anyone, including SMEs and society in general, to mine works to which they have legal access, regardless of the purpose. Furthermore, Article 3 should direct Member States to set up a secure facility to ensure accessibility and verifiability of research made possible through TDM. Under no circumstances should data structured for mining purposes be deleted – this is fundamentally contrary to good scientific practice. Finally, the exception should be protected from being overridden by contract terms, and technological measures should be prohibited that interfere with the exercise of the exception. Both protections are essential for the exception to function.

Education, preservation and access – An enabling environment for Open Science

- Regarding Article 4, we believe that a robust exception to copyright for education should support broad access to and fair reuse of copyrighted content of all types in a variety of education settings, locally and across borders. The scope of the exception should cover digital and non-digital uses, including ‘scientific research’ purposes, alongside educational ones, and prevent rightholders from overriding the exception through contractual provisions or technological protection measures. Finally, the exception should not depend on compulsory remuneration.

- We also urge MEPs to take full account of the views of library and cultural heritage institutions regarding Articles 5-9 of the draft Directive, which aim at ensuring maximising the effective preservation of, and access to works for public interest, non-commercial purposes.

We therefore urge the Legal Affairs Committee to remove Articles 11 and 13 from the draft Directive. Furthermore, we ask for the improvement of Articles 3-9 in line with the suggestions put forward by library, educational, research and cultural heritage organisations throughout the parliamentary process to provide better support for teaching, learning, and new forms of research.

The signatories support a balanced copyright law that promotes open access to research articles, publications and data, thereby continuing to contribute to further strengthening Europe’s research outreach and innovative capacity for the benefit of Europe’s research industry, including SMEs and society.

Original signatories

CESAER – Conference of European Schools for Advanced Engineering Education and Research

COAR – Confederation of Open Access Repositories

Commons Network

Communia Association

Creative Commons

C4C – Copyright for Creativity (C4C) Coalition

EBLIDA – European Bureau of Library Information and Documentation Associations

EIFL – Electronic Information for Libraries

EUA – European University Association

Free Knowledge Advocacy Group EU

IFLA – International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions

LIBER – Association of European Research Libraries

RLUK – Research Libraries UK

Science Europe

SPARC Europe

The post European Parliament Must Protect Scientific Research appeared first on Creative Commons.

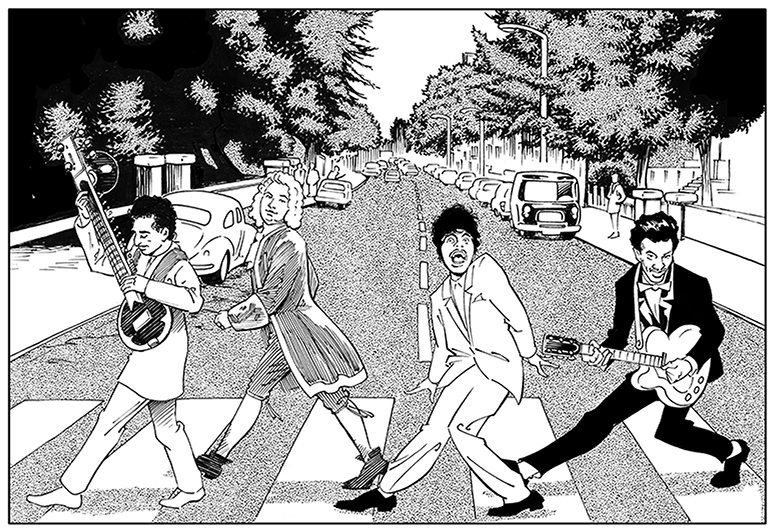

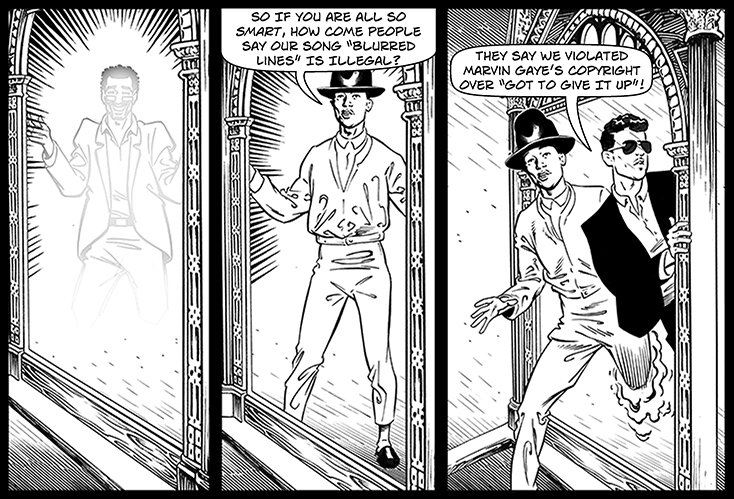

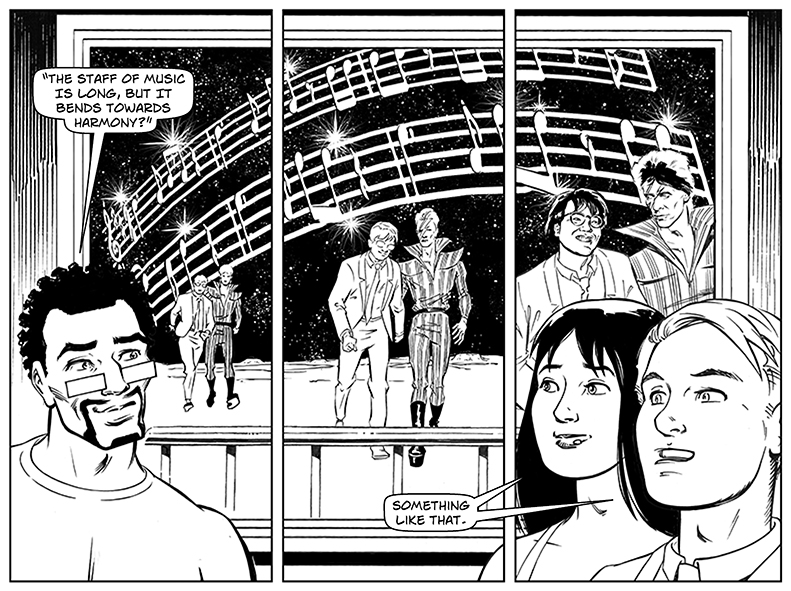

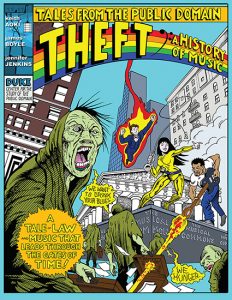

Theft! A History of Music is the newest comic from Jenkins and Boyle, the team behind the 2006 fair use comic Bound by Law. Theft was written in collaboration with the late illustrator and academic Keith Aoki; Boyle and Jenkins developed the graphic designs that were illustrated and inked by Ian Akin and Brian Garvey. The book is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 and is

Theft! A History of Music is the newest comic from Jenkins and Boyle, the team behind the 2006 fair use comic Bound by Law. Theft was written in collaboration with the late illustrator and academic Keith Aoki; Boyle and Jenkins developed the graphic designs that were illustrated and inked by Ian Akin and Brian Garvey. The book is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 and is