You’ve spotted a hot music torrent in the top 100 most popular downloads on The Pirate Bay. You’re keen to obtain it but if you grab it now, the chances are that several anti-piracy companies will monitor the transaction.

You’ve spotted a hot music torrent in the top 100 most popular downloads on The Pirate Bay. You’re keen to obtain it but if you grab it now, the chances are that several anti-piracy companies will monitor the transaction.

Whether that decision will result in a strike on your ISP account, a $3,000 lawsuit, a $20 fine, or absolutely nothing at all, depends largely on a combination of luck and a collision of circumstances. However, a project currently in beta aims to better inform users whether the torrent they’re about to grab is of interest to anti-piracy companies.

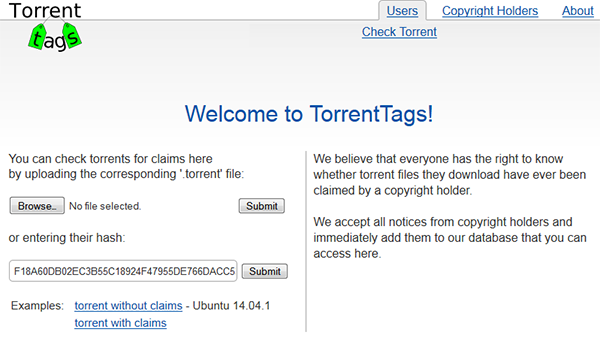

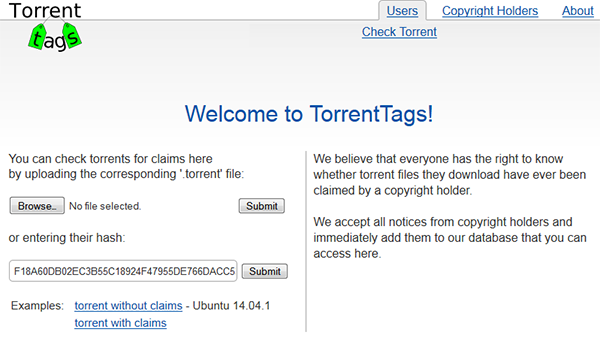

Created by a team of Australian software developers in response to tougher anti-piracy legislation, TorrentTags is currently building a user-searchable database which aims to provide a level of ‘risk’ advice on any given torrent while helping to reduce piracy.

TorrentTags obtains its data in two ways. Firstly, it uses the Chilling Effects database to import the details of torrents that have already been subjected to a DMCA notice on feeder sites including Google search, Twitter and Facebook.

Second, and more controversially, the site is calling on rightsholders to submit details and hashes of content they do not want freely shared on BitTorrent. These can then be added to the TorrentTags database so that when people search for content, warnings are clearly displayed.

“Rightsholders can inform torrent users about copyrighted torrents by sending claims to our database. This is likely to lead to a decrease in the number of downloads of those torrents,” the team informs TF.

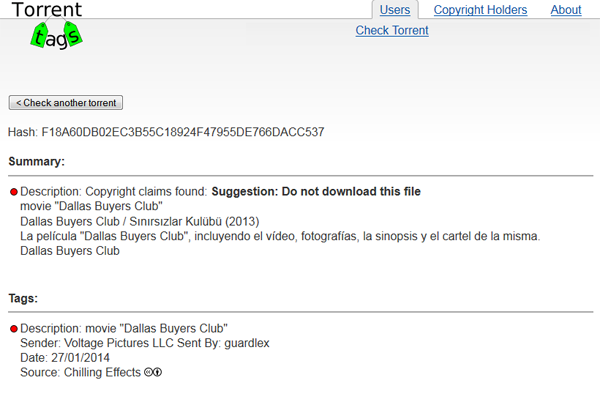

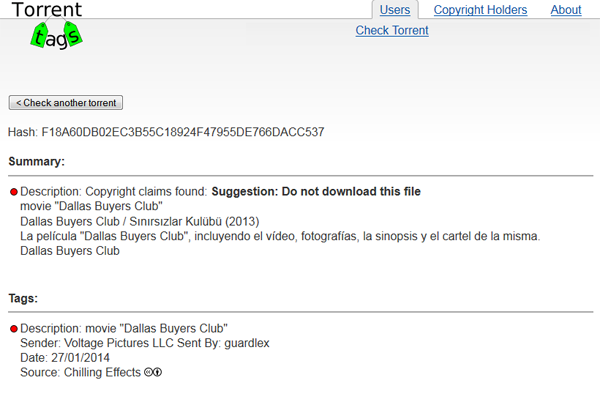

However, the team also views the problem from another angle. Concerned by companies such as Dallas Buyers Club LLC using downloaders as a cash-settlement revenue stream, TorrentTags would like to see public declarations placed on their site to warn potential targets in advance.

“Without a public claim [by copyright holders] the monitoring of users’ activity with the goal of suing would be equivalent to ‘honeypot’ strategies. This is because, from a user’s perspective, any torrent without a public claim is indistinguishable from a torrent created by a copyright owner with the aim of operating a ‘honeypot’,” the team explain.

Warning: Dallas Buyers Club

And herein lies a problem. While it seems unlikely that companies like DBC are operating their own ‘honeypots’, copyright trolls do rely on users sharing their content on BitTorrent in order to track and eventually demand settlement from them. It is therefore unlikely that the most ‘dangerous’ torrents would be voluntarily submitted to TorrentTags by those monitoring them.

It’s certainly possible for information to be added to the database once a lawsuit is made public, but by this time many downloaders will have already been caught. Of course, it may serve as assistance for the future, but it’s also worth noting that Dallas Buyers Club have been suing people publicly for years and still people continue to download the movie.

On the other hand, for companies that simply don’t want their content shared in public, submitting data to a site like TorrentTags might be a way to deter at least some people from downloading their content without permission. Whether they could be encouraged to do so in large volumes remains to be seen – a strong level of participation from a broad range of rightsholders will be required in order to maximize the value of the resource.

While certainly an interesting concept, the TorrentTags team have significant hurdles to overcome to ensure that users of the site aren’t inadvertently misled. Although the importation of millions of notices from Chilling Effects is a good start, the existence of a DMCA notice doesn’t necessarily mean that a torrent is being monitored by trolls. Equally, just because a torrent isn’t listed as ‘dangerous’ it shouldn’t automatically be presumed that it’s safe to download.

In some ways TorrentTags faces some of the same challenges presented to blocklist providers. Although some users swear by them, IP blockers are well-known for not only overblocking, but also letting through a significant number of IP addresses that they should’ve blocked. Time will tell how the balance will be achieved.

Nevertheless, if TorrentTags indeed develops in the manner envisioned by its creators, it could turn into a fascinating resource, not only for BitTorrent users but also those researching anti-piracy methods.

“We hope that TorrentTags will be able to serve as a comprehensive and easily accessible claim database for users. We also hope that TorrentTags will help dissolve the social stigma unjustly associated with Torrents and allow them to be widely used by society for file sharing purposes,” the team conclude.

Source: TorrentFreak, for the latest info on copyright, file-sharing, torrent sites and the best VPN services.

This week we have three newcomers in our chart.

This week we have three newcomers in our chart. The copyright monopoly was reinstated in Great Britain in 1710, after having lapsed in England in 1695. It was enacted because printers (not writers) insisted, that if they didn’t have exclusive rights to boost profitability, nothing would get printed.

The copyright monopoly was reinstated in Great Britain in 1710, after having lapsed in England in 1695. It was enacted because printers (not writers) insisted, that if they didn’t have exclusive rights to boost profitability, nothing would get printed.

You’ve spotted a hot music torrent in the top 100 most popular downloads on The Pirate Bay. You’re keen to obtain it but if you grab it now, the chances are that several anti-piracy companies will monitor the transaction.

You’ve spotted a hot music torrent in the top 100 most popular downloads on The Pirate Bay. You’re keen to obtain it but if you grab it now, the chances are that several anti-piracy companies will monitor the transaction.

Dubbed the “Netflix for Pirates,” the Popcorn Time app quickly gathered a user base of millions of people over the past year.

Dubbed the “Netflix for Pirates,” the Popcorn Time app quickly gathered a user base of millions of people over the past year.

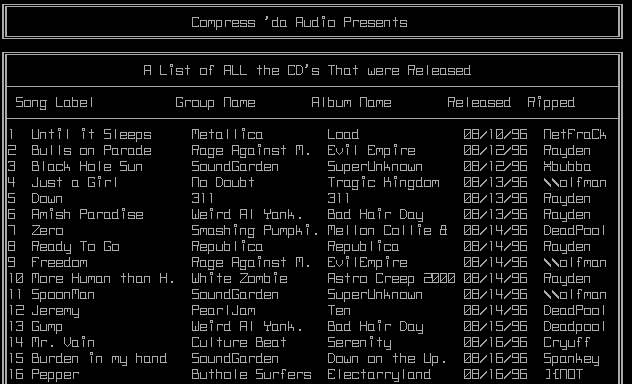

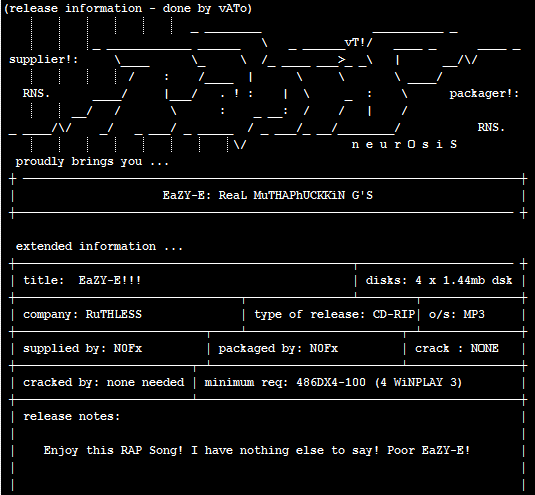

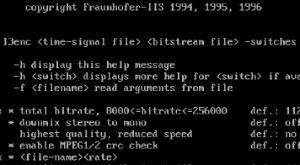

The Dawn of Online Music Piracy

The Dawn of Online Music Piracy