The Internet of Dangerous Things

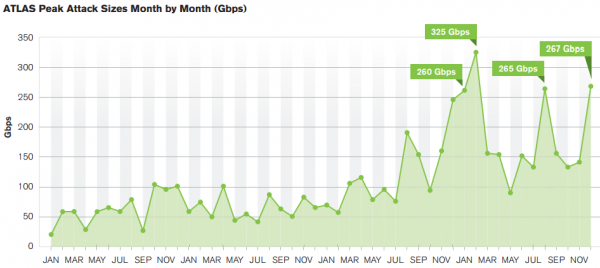

jeudi 29 janvier 2015 à 18:28Distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks designed to silence end users and sideline Web sites grew with alarming frequency and size last year, according to new data released this week. Those findings dovetail quite closely with the attack patterns seen against this Web site over the past year.

Arbor Networks, a major provider of services to help block DDoS assaults, surveyed nearly 300 companies and found that 38% of respondents saw more than 21 DDoS attacks per month. That’s up from a quarter of all respondents reporting 21 or more DDoS attacks the year prior.

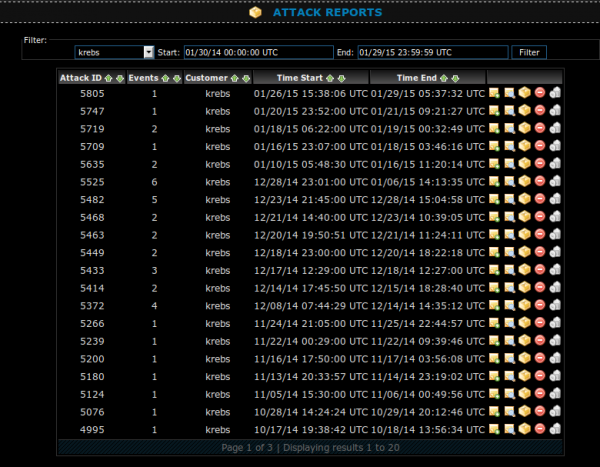

KrebsOnSecurity is squarely within that 38 percent camp: In the month of December 2014 alone, Prolexic (the Akamai-owned company that protects my site from DDoS attacks) logged 26 distinct attacks on my site. That’s almost one attack per day, but since many of the attacks spanned multiple days, the site was virtually under constant assault all month.

Arbor also found that attackers continue to use reflection/amplification techniques to create gigantic attacks. The largest reported attack was 400 Gbps, with other respondents reporting attacks of 300 Gbps, 200 Gbps and 170 Gbps. Another six respondents reported events that exceeded the 100 Gbps threshold. In February 2014, I wrote about the largest attack to hit this site to date — which clocked in at just shy of 200 Gbps.

According to Arbor, the top three motivations behind attacks remain nihilism vandalism, online gaming and ideological hacktivism— all of which the company said have been in the top three for the past few years.

“Gaming has gained in percentage, which is no surprise given the number of high-profile, gaming-related attack campaigns this year,” the report concludes.

Longtime readers of this blog will probably recall that I’ve written plenty of stories in the past year about the dramatic increase in DDoS-for-hire services (a.k.a. “booters” or “stressers”). In fact, on Monday, I published Spreading the Disease and Selling the Cure, which profiled two young men who were running both multiple DDoS-for-hire services and selling services to help defend against such attacks.

The vast majority of customers appear to be gamers using these DDoS-for-hire services to settle scores or grudges against competitors; many of these attack services have been hacked over the years, and the leaked back-end customer databases almost always show a huge percentage of the attack targets are either individual Internet users or online gaming servers (particularly Minecraft servers). However, many of these services are capable of launching considerably large attacks — in excess of 75 Gbps to 100 Gpbs — against practically any target online.

As Arbor notes, some of the biggest attacks take advantage of Internet-based hardware — everything from gaming consoles to routers and modems — that ships with networking features that can easily be abused for attacks and that are turned on by default. Perhaps fittingly, the largest attacks that hit my site in the past four months are known as SSDP assaults because they take advantage of the Simple Service Discovery Protocol — a component of the Universal Plug and Play (UPnP) standard that lets networked devices (such as gaming consoles) seamlessly connect with each other.

In an advisory released in October 2014, Akamai warned of a spike in the number of UPnP-enabled devices that were being used to amplify what would otherwise be relatively small attacks into oversized online assaults.

Akamai said it found 4.1 million Internet-facing UPnP devices were potentially vulnerable to being employed in this type of reflection DDoS attack – about 38 percent of the 11 million devices in use around the world. The company said it was willing to share the list of potentially exploitable devices to members of the security community in an effort to collaborate with cleanup and mitigation efforts of this threat.

That’s exactly the response that we need, because there are new DDoS-for-hire services coming online every day, and there are tens of millions of misconfigured or ill-configured devices out there that can be similarly abused to launch devastating attacks. According to the Open Resolver Project, a site that tracks devices which can be abused to help launch attacks online, there are currently more than 28 million Internet-connected devices that attackers can abuse for use in completely anonymous attacks.

Tech pundits and Cassandras of the world like to wring their hands and opine about the coming threat from the so-called “Internet of Things” — the possible security issues introduced by the proliferation of network-aware devices — from fitness trackers to Internet-connected appliances. But from where I sit, the real threat is from The Internet of Things We Already Have That Need Fixing Today.

To my mind, this a massive problem deserving of an international and coordinated response. We currently have global vaccination efforts to eradicate infectious and communicable but treatable diseases. Unfortunately, we probably need a similar type of response to deal with the global problem of devices that can be conscripted at a moment’s notice to join a virtual flash mob capable of launching attacks that can knock almost any target offline for hours or days on end.

Anyone who needs a reminder of just how bad the problem is need only look to the attacks of Christmas Day 2014 that took out the Sony Playstation and Microsoft Xbox gaming networks. Granted, those companies were already dealing with tens of millions of new customers that very same day, but as I noted in my Jan. 9 exclusive, the DDoS-for-hire service implicated in that attack (or at least the attackers) was built using a few thousand hijacked home Internet routers.

[Author’s note: The headline for this post was inspired by Glenn Fleishman‘s excellent Jan. 13, 2015 piece in MIT Technology Review, An Internet of Treacherous Things.]