In Damage Control, Sony Targets Reporters

lundi 15 décembre 2014 à 15:35Over the weekend I received a nice holiday letter from lawyers representing Sony Pictures Entertainment, demanding that I cease publishing detailed stories about the company’s recent hacking and delete any company data collected in the process of reporting on the breach. While I have not been the most prolific writer about this incident to date, rest assured such threats will not deter this reporter from covering important news and facts related to the breach.

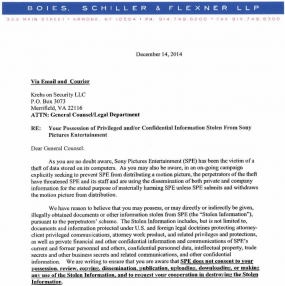

“SPE does not consent to your possession, review, copying, dissemination, publication, uploading, downloading, or making any use of the Stolen information, and to request your cooperation in destroying the Stolen Information,” wrote SPE’s lawyers, who hail from the law firm of Boies, Schiller & Flexner.

This letter reminds me of one that I received several years back from the lawyers of Igor Gusev, one of the main characters in my book, Spam Nation. Mr. Gusev’s attorneys insisted that I was publishing stolen information — pictures of him, financial records from his spam empire “SpamIt” — and that I remove all offending items and publish an apology. My lawyer in that instance called Gusev’s threat a “blivit,” a term coined by the late, great author Kurt Vonnegut, who defined it as “two pounds of shit in a one-pound bag.”

For a more nuanced and scholarly look at whether reporters and bloggers who write about Sony’s hacking should be concerned after receiving this letter, I turn to an analysis by UCLA law professor Eugene Volokh, who posits that Sony “probably” does not have a legal leg to stand on here in demanding that reporters refrain from writing about the extent of SPE’s hacking in great detail. But Volokh includes some useful caveats to this conclusion (and exceptions to those exceptions), notably:

“Some particular publications of specific information in the Sony material might lead to a successful lawsuit,” Volokh writes. “First, disclosure of facts about particular people that are seen as highly private (e.g., medical or sexual information) and not newsworthy might be actionable under the ‘disclosure of private facts’ tort.”

Volokh observes that if a publication were to publish huge troves of data stolen from Sony, doing so might be seen as copyright infringement. “The bottom line is that publication of short quotes, or disclosure of the facts from e-mails without the use of the precise phrasing from the e-mail, would likely not be infringement — it would either be fair use or the lawful use of facts rather than of creative expression,” he writes.

Volokh concludes that Sony is unlikely to prevail — “either by eventually winning in court, or by scaring off prospective publishers — especially against the well-counseled, relatively deep-pocketed, and insured media organizations that it’s threatening,” he writes. “Maybe the law ought to be otherwise (or maybe not). But in any event this is my sense of the precedents as they actually are.”

This is actually the second time this month I’ve received threatening missives from entities representing Sony Pictures. On Dec. 5, I got an email from a company called Entura, which requested that I remove a link from my story that the firm said “allowed for the transmission and/or downloading of the Stolen Files.” That link was in fact not even a Sony document; it was a derivative work — a lengthy text file listing the directory tree of all the files stolen and leaked (at the time) from SPE. Needless to say, I did not remove that link or file.

Here is the full letter from SPE’s lawyers (PDF).