Don’t Be Fodder for China’s ‘Great Cannon’

vendredi 10 avril 2015 à 12:12China has been actively diverting unencrypted Web traffic destined for its top online search service — Baidu.com — so that some visitors from outside of the country were unwittingly enlisted in a novel and unsettling series of denial-of-service attacks aimed at sidelining sites that distribute anti-censorship tools, according to research released this week.

The findings, published in a joint paper today by researchers with University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab, the International Computer Science Institute (ICSI) and the University of California, Berkeley, track a remarkable development in China’s increasingly public display of its evolving cyber warfare prowess.

“Their willingness to be so public mystifies me,” said Nicholas Weaver, a researcher at the ICSI who helped dig through the clues about the mysterious attack. “But it does appear to be a very public statement about their capabilities.”

Earlier this month, Github — an open-source code repository — and greatfire.org, which distributes software to help Chinese citizens evade censorship restrictions enacted by the so-called “Great Firewall of China,” found themselves on the receiving end of a massive and constantly-changing attack apparently designed to prevent people from being able to access the sites.

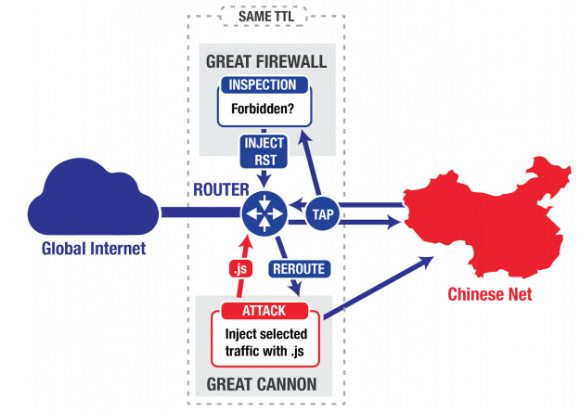

Experts have long known that China’s Great Firewall is capable of blocking Web surfers from within the country from accessing online sites that host content which is deemed prohibited by the Chinese government. But according to researchers, this latest censorship innovation targeted Web surfers from outside the country who were requesting various pages associated with Baidu, such that Internet traffic from a small percentage of surfers outside the country was quietly redirected toward Github and greatfire.org.

This attack method, which the researchers have dubbed the “Great Cannon,” works by intercepting non-Chinese traffic to Baidu Web properties, Weaver explained.

“It only intercepts traffic to a certain set of Internet addresses, and then only looks for specific script requests. About 98 percent of the time it sends the Web request straight on to Baidu, but about two percent of the time it says, ‘Okay, I’m going to drop the request going to Baidu,’ and instead it directly provides the malicious reply, replying with a bit of Javascript which causes the user’s browser to participate in a DOS attack, Weaver said.

The researchers said they tracked the attack for several days after Github apparently figured out how to filter the malicious traffic, which relied on malicious Javascript files that were served to visitors outside of China that were browsing various Baidu properties.

Chillingly, the report concludes that Chinese censors could just have easily served malicious code to exploit known Web browser vulnerabilities.

“With a minor tweak in the code, they could have provided exploits to targeted [Internet addresses], so that instead of intercepting all traffic to Baidu, they would serve malware attacks to those visitors,” Weaver said.

Interestingly, this type of attack is not unprecedented. According to documents leaked by National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden, the NSA and British intelligence services used a system dubbed “QUANTUM” to inject content and modify Web results for individual targets that appeared to be coming from a pre-selected range of Internet addresses.

“The Chinese government can credibly say the United States has done similar things in the past,” Weaver said. “They can’t say we’ve done large scale DDoS attacks, but the Chinese government can honestly state that the U.S. has modified traffic in-flight to attack and exploit systems.”

Weaver said the attacks from the Great Cannon don’t succeed when people are browsing Chinese sites with a Web address that begins with “https://”, meaning that regular Internet users can limit their exposure to these attacks by insisting that all Internet communications are routed over “https” versus unencrypted “http://” connections in their browsers. A number of third-party browser plug-ins — such as https-everywhere — can help people accomplish this goal.

“The lesson here is encrypt all the things all the time always,” Weaver said. “If you have to worry about a nation state adversary and if they can see an unencrypted web request that they can tie to your identity, they can use that as a vehicle for attack. This has always been the case, but it’s now practice.”

But Bill Marczak, a research fellow with Citizen Lab, said relying on an always-on encryption strategy is not a foolproof counter to this attack, because plug-ins like https-everywhere will still serve regular unencrypted content when Web sites refuse to or don’t offer the same content over an encrypted connection. What’s more, many Web sites draw content from a variety of sources online, meaning that the Great Cannon attack could succeed merely by drawing on resources provided by online ad networks that serve ads on a variety of Web sites from a dizzying array of sources.

“Some of the scripts being injected in this attack are from online ad networks,” Marczak said. “But certainly this kind of attack suggests a far more aggressive use of https where available.”

For a deep dive into the research referenced in this story, check out this link.